Hard optimization problems have soft edges

Hard optimization problems have soft edges"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Finding a Maximum Clique is a classic property test from graph theory; find any one of the largest complete subgraphs in an Erdös-Rényi _G_(_N_, _p_) random graph. We use Maximum

Clique to explore the structure of the problem as a function of _N_, the graph size, and _K_, the clique size sought. It displays a complex phase boundary, a staircase of steps at each of

which \(2 \log _2N\) and \(K_{\text {max}}\), the maximum size of a clique that can be found, increases by 1. Each of its boundaries has a finite width, and these widths allow local

algorithms to find cliques beyond the limits defined by the study of infinite systems. We explore the performance of a number of extensions of traditional fast local algorithms, and find

that much of the “hard” space remains accessible at finite _N_. The “hidden clique” problem embeds a clique somewhat larger than those which occur naturally in a _G_(_N_, _p_) random graph.

Since such a clique is unique, we find that local searches which stop early, once evidence for the hidden clique is found, may outperform the best message passing or spectral algorithms.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS CLIQUE HOMOLOGY IS \({{\MATHSF{QMA}}}_{1}\)-HARD Article Open access 13 November 2024 CONTINUED FRACTIONS AND THE THOMSON PROBLEM Article Open access

04 May 2023 FAST AND SCALABLE LIKELIHOOD MAXIMIZATION FOR EXPONENTIAL RANDOM GRAPH MODELS WITH LOCAL CONSTRAINTS Article Open access 27 July 2021 INTRODUCTION Phase transitions and phase

diagrams describing the behavior of combinatorial problems on random ensembles are no longer surprising. Large scale data structures arise in practical examples, such as the analysis of

large amounts of social data, extending to the activities of a few billion people. Effective tools for managing them have commercial value. The model system and the forms of interactions

that couple its elements in data science are known. While exact methods can solve only very small examples, approximate simulation of medium scale problems must reach very large scale.

Methods such as finite-size scaling analysis expose regularities1. Classic examples include the Satisfiability problem in its many variants2,3. In this paper, we consider finding maximum

cliques in random graphs, specifically Erdös-Rényi4,5 graphs of the _G_(_N_, _p_) class, with _N_ nodes (or sites) and each edge (or bond) present with probability _p_. We further specialize

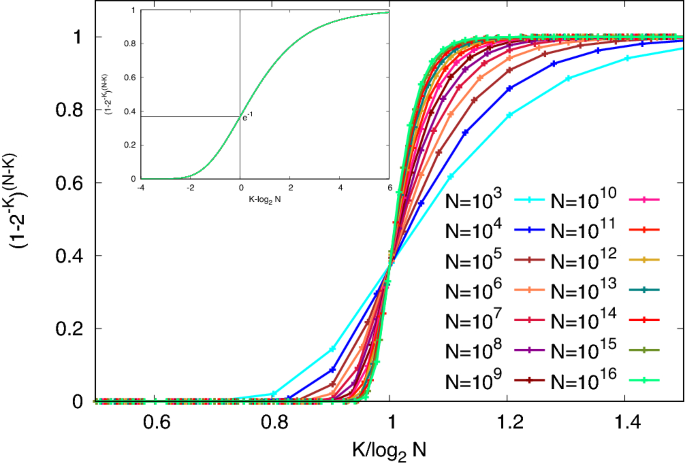

to the case \(p = 1/2\). Maximum Clique is an unusually difficult problem, for which naive solution methods (Fig. 1) can construct cliques of size \(K=\log _2 N\), yet probabilistic

arguments show that solutions asymptotically of size \(2\log _2 N\) must exist. No polynomial algorithms that will construct true maximum cliques for arbitrarily large values of _N_ are

known. The failure is general, not merely a problem for the rare worst case. We shall test several fast algorithms of increasing complexity to determine the range of _N_ at which each gives

useful answers. Greedy methods are fast, and a good starting point for our discussion. Start with a site anywhere in the graph, and discard roughly half of the sites that are not neighbors.

Pick a neighbor from the _frontier_ that remains. Then discard half of the remaining sites that are not a neighbor of the new site. Continue in this way until the _frontier_ vanishes—no

candidates to extend the clique remain. Since we have halved the size of the frontier at each step, it is unlikely that this process can proceed beyond \(\log _2 N\) steps6. Let’s look at

this more precisely, as a function of _N_. The stopping probability, that we can find no other site to grow from size _K_ to \(K+1\) is \((1-2^{-K})^{(N-K)}\), as shown in Fig. 1, where use

of a common scale \(K/\log _2 N\), brings the various curves all together at a probability of \(e^{-1}\) when _K_ is equal to \(\log _2 N\). All cliques are extendable when \(K<< \log

_2 N\), and none are when \(K>>\log _2 N\). The slopes of these curves are each proportional to \(\log _2 N\). The simple expedient of plotting the curve for each value of _N_ against

\(K - \log _2 N\) collapses all of them to a universal limiting form, which is shown in the inset to Fig. 1. This is finite-size scaling just as seen in phase transitions1. It also shows

that cliques selected at random from the large number which we know must exist start to be non-extendable at a size two sites below \(\log _2 N\) boundary and are almost never extendable

four sites above, with a functional form that is almost independent of _N_. This threshold occurs for each _N_ at \(K = \log _2 N\), and has a width in _K_ which is independent of _N_.

Matula first called attention to several interesting aspects of the Maximum Clique problem on _G_(_N_, _p_). From the expected number of cliques _n_(_K_, _N_), of size _K_ at \(p = 1/2\)7:

$$\begin{aligned} n(K,N) = {N \atopwithdelims ()K} 2^{-{K \atopwithdelims ()2}}, \end{aligned}$$ (1) using Stirling’s approximation, one can see that this is large at \(K = \log _2 N\) but

becomes vanishingly small for \(K > 2\log _2 N\), providing an upper bound to _K_. Matula identified \(K_{\text {max}}\) as the largest integer such that $$\begin{aligned} n(K_{\text

{max}},N ) \ge 1. \end{aligned}$$ (2) and7,8 expanded the finite _N_ corrections to the continuous function _R_(_N_) solving \(n(R,N) = 1\): $$\begin{aligned} R(N)=2\log _2 N-2\log _2 \log

_2 N+2 \log _2 e. \end{aligned}$$ (3) This formula is also discussed in Bollobás and Erdös9 and by Grimmett and McDiarmid10. We will focus on \(K_{\text {max}}\), the predicted actual

maximum clique size. In effect, its value follows a staircase with the prediction (3) passing through the risers between steps, as shown in Fig. 2. Across each step \(n(K_{\text {max}},N)\)

grows from 1 to \(\mathscr {O}(N)\). The number of maximum cliques per site in the graph that results is shown in Fig. 3. We see that at the left edge of each step, cliques of size

\(K_{\text {max}}\) are very rare, but at the right edge of that step, each site is possibly contained in multiple maximal cliques, while cliques of size \(K_{\text {max}} + 1\) have an

expectation which has reached 1. Thus across each step, the probability of finding a clique of larger _K_ decreases by a factor of \({\mathscr {O}}(N)\) for each increase by 1 in _K_. Matula

drew attention to a _concentration_ result for the clique problem. As \(N \rightarrow \infty\) the sizes of the largest cliques that will occur are concentrated on just two values of _K_,

the integers immediately below and above _R_(_N_). From the second moment of the distribution of the numbers of cliques of size _K_ one can bound the fraction of graphs with no such cliques,

and sharpen the result11 by computing a weighted second moment. In effect, Markov’s inequality provides upper bounds, and Chebyscheff’s inequality provides lower bounds on the existence of

such cliques. The probability that the maximum clique size is \(K_{\text {max}}\) was given by Matula7,8,11. The fraction of graphs _G_(_N_, _p_) with maximum clique size \(K_{\text

{max}}\), is bounded as follows: $$\begin{aligned} \left( \mathop {\sum }\limits _{j=\text {max}\{0, 2k-N\}}^k \frac{{N-k \atopwithdelims ()k-j}{k \atopwithdelims ()j}}{{N \atopwithdelims

()k}} p^{-{j \atopwithdelims ()2}} \right) ^{-1}\le \text {Prob}(K_{\text {max}}\ge k) \le {N \atopwithdelims ()k} p^{k \atopwithdelims ()2}. \end{aligned}$$ (4) This leads to the following

picture, evaluated for two values of _N_, one small and one quite large, in Fig. 4, we see that at the step between two integer values of \(K_{\text {max}}\), more than half of the graphs

will have a few cliques of the new larger value from the upper step, and less than half will have only cliques with the smaller value from the lower step, but many of them. Figure 4 shows

that the crossover at each step edge narrows with increasing _N_, but only very slowly. The two cases sketched correspond to steps at roughly \(N = 1.2\, 10^3\) and \(N = 1.3 \, 10^6\). For

the case at smaller _N_, the transition is spread over almost half the width of the step. As in Fig. 1, the transition is not symmetric. The appearance of cliques with the new value of

\(K_{\text{ max }}\) is sharper and comes closer to the step than the disappearance of cases in which the cliques from the previous step still dominate. Because the natural scale of this

problem is \(\log _2 N\), we see that the width of the transition from one step to the next remains important on the largest scales encountered in actual data networks, such as \(N \sim

10^9\), the population of the earth. The traditional approach to surveying and challenging the developers of algorithms for solving hard problems is to assemble a portfolio of such problems,

some with a known solution, and some as yet unsolved. The DIMACS program at Rutgers carried out such a challenge in the mid 1990’s12. Roughly a dozen groups participated over a period of a

year or more, and the sample graphs continue to be studied. The largest graphs in the portfolio were random graphs of size 1000 to 2000, and the methods available gave results for these

which fell at least one or two short of _R_(_N_). As a result, the actual values of \(K_{\text {max}}\) for many test graphs are still unknown. A better test for these algorithms on random

graphs is to determine to what extent they can reproduce the predicted distribution of results that we see in Fig. 4, both the steps in \(K_{\text {max}}\) and the fraction of graphs with

each of the dominant values of \(K_{\text {max}}\) as it evolves with increasing _N_. We will present extensions of the algorithms tested at DIMACS and show that they give good results on

sets of problems larger than those in the DIMACS portfolio. Several authors have proposed that the search for powerful, effective clique-finding algorithms could be expressed as a

_challenge_. Mark Jerrum, in his 1992 paper _“Large Cliques Elude the Metropolis Process”_,13 sets out several of these. His paper shows that a restricted version of stochastic search is

unlikely to reach a maximum clique, and also introduces the additional problem of finding an artificially _hidden clique_, which we discuss in a later section. A hidden clique or _planted

solution_, is just what it sounds like, a single subgraph of \(K_{HC}\) sites, with \(K_{HC} > K_{\text {max}}\), so that it can be distinguished, for which all the missing bonds among

those sites have been restored. A series of papers14,15 show that if \(K_{HC}\) is of order \(N^{\alpha }\) with \(\alpha > 0.5\), a small improvement over our naive greedy algorithm

(\(SM^{0}\) introduced in the next section) will find such a hidden clique, simply by favoring sites in the frontier with the most neighbors in its search. Jerrum’s first challenge is to

find a hidden subgraph of size \(\sim N^{0.5 - \epsilon }\) with probability greater than 1/2, using an algorithm whose cost is polynomial in the number of bonds in the graph (i.e. \(N^2\)

is considered to be a linear cost). We see below that the range of hidden clique sizes that can be hidden between \(N^{1/2}\) and the naturally-occurring cliques of size \(2 \log _2N\) is

not large. So practically oriented work has focused on finding hidden cliques of size \(\alpha N^{1/2}\) for \(\alpha < 1\). Karp in his original paper, Jerrum, and several others have

also turned the identification of any naturally occurring clique larger than \(\log _2 N\) into such a challenge: find any clique of size exceeding \(\log _2 N\) with probability exceeding

1/2. We saw in the discussion of Fig. 1 that finding cliques which exceed \(\log _2 N\) by a small constant number of sites should be straightforward at any value of _N_. We shall see that

both challenges can be met for large, finite, and thus interesting values of _N_, and will attempt to characterize for what range of _N_ they remain feasible. Below, in “Greedy algorithms”

section, we introduce a class of greedy algorithms, of complexity polynomial in _N_, and test the accuracy with which they reflect the size and distribution of the maximum cliques present in

\(G(N,p=1/2)\) for useful sizes of _N_. In “Hidden clique” section, we review the “hidden clique” variant of the Maximum Clique problem, and describe its critical difference from the

problem treated in “Greedy algorithms” section (that the hidden clique is unique, while naturally occurring cliques are many). We show that our greedy algorithms can exploit this difference

to perform as well as or better than the best proposed methods in the literature. “Conclusions” section summarizes our conclusions and provides recommendations for future work. GREEDY

ALGORITHMS In this section, we describe the performance of a family of increasingly powerful greedy algorithms for constructing a maximal clique on an undirected graph. Those algorithms are

polynomial in time and use some randomness, but they are myopic in generating optimal solutions. However, because they are relatively fast, significant research effort has been devoted to

improving their performance while adding minimal complexity. We will show ways of combining several of these simple greedy algorithms, to obtain better solutions at somewhat lower cost by

adding a very limited form of back-tracking. We start by considering a simple family of greedy algorithms, designated by Brockington and Culberson16, as \(SM^{i}\), \(i=0,1,2..\). \(SM^{0}\)

improves over the naive approach we described at the outset17, by selecting at each stage the site with the largest number of neighbors to add to the growing clique. If there are many such

sites to choose from, each connected to all of the sites in the part of the clique identified to that point, one is chosen at random, so multiple applications of \(SM^{0}\) will provide a

distribution of answers for a given graph _G_(_N_, _p_). At each stage this choice of the site to add retains somewhat more than half of the remainder of the graph, _Z_, so the resulting

clique will be larger than \(\log _2 N\), for all _N_. \(SM^0\) can be implemented to run in \({\mathscr {O}}(N^2)\) time. \(SM^{i}\) for \(i=1, 2,...\) are algorithms in which we start our

greedy construction with each combination of _i_ vertices which form a complete subgraph, then extend them one site at a time using \(SM^0\). In other words, \(SM^{0}\) is run starting with

each of \({N \atopwithdelims ()i} p^{{i \atopwithdelims ()2}}\) complete subgraphs of order _i_. \(SM^{1}\), starting with every site, can be implemented to run in \({\mathscr {O}}(N^3)\).

The complexity of \(SM^{2}\), which uses all connected pairs, is \({\mathscr {O}}(N^4)\). The computational complexity for the class of algorithms \(SM^{i}\) is \({\mathscr {O}}(N^{i+2})\).

In Fig. 5 we show the sizes of the maximal cliques on Erdös-Rényi graphs \(G(N, p=0.5)\), found using the algorithms \(SM^{i}\), with \(i=0, 1, 2\). For comparison, we plot the green

staircase, \(K_{\text {max}}\). This figure shows the improvements that result from the (considerable) extra computational cost of the latter two algorithms. Both the blue points of

\(SM^{1}\) and the orange points of \(SM^{2}\) reflect the staircase of \(K_{\text {max}}\). Even their error bars reflect the rapid increase of the number of the larger maximum cliques

after each jump in the staircase. The error bars on the red points of \(SM^{0}\) do not show any staircase pattern. \(SM^{0}\), even with error bars, lies consistently above \(\log _2 N\).

Each red point is the average over 2000 random Erdös-Rényi graphs, each blue point is the average over 500 random Erdös-Rényi graphs, and each coral point is the average over 100 random

Erdös-Rényi graphs. We have used a uniform random number generator with an extremely long period (WELL1024)18. The \(SM^{2}\) results track the staircase closely up to \(N = 4000\), a larger

size than seen in the DIMACS study, while the \(SM^{1}\) results fall about 1 site below the staircase at the end of this range. Figure 6 gives a more detailed comparison of the two

algorithms. Figure 6 compares the predicted fraction of random Erdös-Rényi graphs having a maximal clique size with the experimental results obtained with the two algorithms around the step

from \(K_{\text {max}} = 15\) to 16. This corresponds to the region most often explored in the DIMACS studies. The \(SM^{2}\) algorithm remains within the bounds described by Matula. The

red, purple, and blue filled square points in the three predicted probability regions (red, purple, and blue, respectively) find acceptable fractions of 15, 16, and even 17 sites cliques as

_N_ is increased. The \(SM^{1}\) algorithm, shown by orange, pink, and blue open squares, falls short in all three probability regions, finding too many 15’s, too few 16’s, and no 17’s. The

two algorithms both provided similar distributions of results up to \(N = 300\) of \(K_{\text {max}} = 12\). These two algorithms are very expensive. We could only analyze rather small

random graphs, comparable to the larger DIMACS examples. The results fall within the calculated distribution, which is a valuable check, since the actual value of \(K_{\text {max}}\) is

unknown for an individual graph. Next, we consider less costly algorithms, which allow us to explore much larger graphs. These give results lying between \(SM^{0}\) and \(SM^{2}\) and still

reflect the staircase character of the underlying problem. We reverse the order of operations made by the class of algorithm \(SM^{i}\), with \(i=1, 2,..\). Instead of running \(SM^{0}\) for

each pair, or triangle, or tetrahedron (etc.) in the original graph, we run \(SM^{i}\), with \(i=1, 2,..\) fixed, but only on the sites found within one solution given by \(SM^{0}\).

\(SM^0\) will return a clique _C_ of size |_C_|. On this solution we run \(SM^i\), i.e. we select all the possible \({|C|\atopwithdelims ()i}\) complete subgraphs in the clique _C_, and, on

each of them, we run \(SM^0\). This simple algorithm, which we call \(SM^0 \rightarrow SM^i\), will run in a time bounded by \(\mathscr O(N^2 \ln N)\). We have analyzed the results of the

algorithm \(SM^{0}\rightarrow SM^{i}\), with _i_ fixed to 4, compared to \(SM^0\) in the range of _N_ [2800:50,000]. Thus we analyzed \({|C|\atopwithdelims ()4}\) graphs of order

approximately _N_/16. The combined algorithm \(SM^{0}\rightarrow SM^{4}\) always finds a maximal clique bigger than those given by \(SM^0\) alone. Moreover, the combined algorithm reproduces

the wiggling behaviour due to the discrete steps in \(K_{\text {max}}\) in a time bounded by \({\mathscr {O}}(N^2 \ln N)\), while \(SM^{0}\), used alone, does not. The improved results of

the combined algorithm \(SM^{0} \rightarrow SM^{i}\), with fixed _i_, suggests iterating the procedure. First we run \(SM^{i}\), with fixed _i_, on the clique returned by \(SM^{0}\). If the

clique returned by the algorithm is bigger than the one that is used for running \(SM^{i}\), then we use the new clique as a starting point where \(SM^{i}\) will be run again. The algorithm

stops when the size of the clique no longer increases. The complexity of the algorithm, therefore, is \({\mathscr {O}}(tN^2 \ln N)\), where _t_ is the number of times we find a clique which

is bigger than the previous one. We call this new algorithm \(SM^{0}\rightarrow \text {iter}[SM^{i}]\). We present in Fig. 7 the results of \(SM^{0}\rightarrow \text {iter}[SM^{i}]\), over

the full range of _N_ from 100 to 100,000. We use different _i_ in different ranges of _N_, determining their values by experiments. As _N_ increases we have to increase the number of sites

kept for the iteration in order to get a bigger complete subgraph at the end of the process. The values of _i_ selected are given in Table 1 Figure 7 shows the results of experiments with

\(SM^{0}\rightarrow \text {iter}[SM^{i}]\), with _i_ fixed in the range given by Table 1. They fall between two _staircases_. The upper one is \(K_{\text {max}}\), as before, and the lower

one is the max clique size predicted by the first moment bound if we begin with a randomly selected clique of size _i_. The coloured staircase curve is given by19 the smallest value of _K_

for which: $$\begin{aligned} {N - i \atopwithdelims ()K -i }p^{{K\atopwithdelims ()2}-{i\atopwithdelims ()2}} \ge 1. \end{aligned}$$ (5) This implies that the subgraphs we have selected as a

basis for our iteration are much better than average, compared with the very large number of starting subgraphs that a full \(SM^i\) would have needed to search. Also, while the slope of

the \(SM^0\) results is no greater than 1 on this plot at larger values of _N_, the iterated results are rising with a higher slope all the way to \(N = 10^5\). To get a more objective

standard of difficulty, we use the ideas of the Overlap Gap Property (OGP)20, but apply it at finite scales. The expected number of combinations of overlapping clusters in this model is

easily calculated. In Fig. 8 we show the expected number of cliques of size _K_ that overlap a single randomly chosen clique of the same size on precisely _j_ sites. Values of _K_ range from

\(\log _2N\) to \(K_{\text {max}} - 1\). We define \(K_1\) as the largest value of _K_ for which cliques of size _K_ have some overlaps at all values of _j_. A local search, which moves

from one clique to another by changing only one site at a time can still visit all possible cliques of sizes \(K_1\) or less. At fixed _N_, cliques larger than \(K_1\) will have an overlap

gap and will occur only in tiny clusters that differ in a few sites, touching other cliques of the same size only at their edges. This gap opens up when the overlap _j_ is roughly \(\log _2

N\), so we see that \(K_1 (N)\) is somewhat larger than \(\log _2 N\). From plots like Fig. 8, evaluated at the step edges seen for values of _N_ from \(10^3\) to \(5\,10^4\), we find values

of \(K_1/ \log _2 N\) decreasing slowly from 1.34 to 1.24. This sets a bound on the values that \(SM^{0}\) could discover across this range of _N_. In fact, results of \(SM^{0}\) decreased

from \(1.2 \log _2 N\) to \(1.17 \log _2 N\) across this range. However, our results with algorithms \(SM^1\) and \(SM^2\), seen in Fig. 7, which reduce confusion by a limited amount of

backtracking, exceed it. At step edges, they range from 1.39 to \(1.36 \log _2 N\). The prefactor is still decreasing with increasing _N_, but exceeds the suggested OGP limit. HIDDEN CLIQUE

To “hide” a clique for computer experiments, it is conventional to use the first \(K_{HC}\) sites as the hidden subset, which makes it easy to observe the success or failure of oblivious

algorithms. But this is an entirely different problem than Maximum Clique. Since the hidden clique is unique and distinguished from the many accidental cliques by its greater size, there is

no confusion to obstruct the search. We construct the hidden clique in one of two ways. The first is simply to restore all the missing links among the first \(K_{HC}\) sites. This has the

drawback that those sites will have more neighbors than average, and might be discovered by exploiting this fact. In fact, the upper limit to interesting hidden clique sizes was pointed out

by Kučera21, who showed that a clique of size \(\alpha \sqrt{N \ln N}\) for a sufficiently large \(\alpha\) will consist of the sites with the largest number of neighbors, and thus can be

found by \(SM^0\). The second method is to move links around within the random graph in such a way that after the hidden clique is constructed, each site will have the same number of links

that it had before. To do this, before we add a link between sites _i_ and _j_ in the hidden clique, we select at random two sites, _k_ and _l_, which lie outside the clique. _k_ must be a

neighbor of _i_ and _l_ must be a neighbor of _j_. If _k_ and _l_ are distinct and not neighbors, we create a new link between them, and remove the links between _i_ and _k_ and between _j_

and _l_. If this fails we try the replacement again, still selecting sites _k_ and _l_ at random. The result is a new graph with the same distribution of connectivities, as measured from the

individual sites. This sort of _smoothing_ of the planting of a hidden clique had been explored by22. Several graphs prepared in this way are in the DIMACS portfolio, and are said to be

more difficult to solve. In the results we report below, we have used only the first method, as we found no difference resulted when studying hidden cliques in the region of greatest

interest, close to the naturally occurring sizes. A stronger result, by Alon et al.14 uses spectral methods to show that a hidden clique, _C_, of cardinality \(|C|\ge 10 \sqrt{N}\) can be

found with high probability, in polynomial time. Dekel et al.15 showed that with a linear (\({\mathscr {O}}( N^2)\), the number of links) algorithm the constant can be reduced to 1.261. Our

experiments, using this approach, were successful to a slightly lower value, of roughly 1.0. Finally, recent work of Deshpande and Montanari23 has shown that Approximate Message Passing

(AMP), a form of belief propagation, can also identify sites in the hidden clique. This converges down to \(\sqrt{N/e}\), where _e_ is Euler’s constant (see Fig. 9). No algorithm currently

offers to find a clique of size less than \(\sqrt{N/e}\) and bigger than \(K_{\text {max}}\), in quasi-linear time, for arbitrary _N_. Parallel Tempering enhanced with an early stopping

strategy24,25, is able to explore solutions below \(\sqrt{N/e}\), but only at the expense of greatly increased computational cost. Some of these procedures identify some, but perhaps not all

of the planted clique sites, and require some “_cleanup_” steps to complete the identification of the whole clique. The cleanup procedures all require starting with either a subset of the

hidden clique sites and finding sites elsewhere in the graph that link to all of them, or eliminating the sites in a possible mixed subset of valid and incorrect choices which do not extend

as well, or doing both in some alternating process. These can be proven to work if the starting point is sufficiently complete (hence Alon et al.’s \(C = 10\) starting point). We find

experimentally, and discuss below, that a cleanup process can be effective given a much poorer starting point. ITERATIVE METHODS Next, we consider methods of searching for the hidden clique

that involve iteration. We shall employ two approaches, the \(SM^1\) greedy algorithm with a simple modification, and the belief propagation scheme introduced by Deshpande and Montanari23.

First, we must make a further modification of the adjacency matrix. We will use \(\widetilde{{\mathbf{A}}}\), whose elements are defined by: $$\begin{aligned}

\begin{aligned}{}&{\tilde{A}}_{ij} = { {\tilde{a}}_{ij} },\\&{\tilde{a}}_{ij} = {\tilde{a}}_{ji}, \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$ where \({\tilde{a}}_{ij}=1\) if the link is present,

\({\tilde{a}}_{ij}=-1\) if the link is absent, and \({\tilde{a}}_{ii}=0\). The reason for the extra nonzero entries is simple. It generates the same band of eigenvalues, with doubled width,

and moves the special uniform state at \(0.5 \sqrt{N}\) into the center of the band, where it no longer interferes with the influence of eigenstates at the top of the energy band, which are

most likely to contain the hidden clique sites. Now we considered the AMP algorithm introduced by Deshpande et al. in23. They proved that as \(N \rightarrow \infty\) their algorithm is able

to find hidden cliques of size \(K_{HC} \ge \sqrt{N/e}\) with high probability. AMP is derived as a form of _belief propagation_ (BP), a heuristic machine learning method for approximating

posterior probabilities in graphical models. BP is an algorithm26,27,28, which extracts marginal probabilities for each variable node on a factor graph. It is exact on trees, but was found

to be effective on loopy graphs as well23,29,30,31. It is an iterative message passing algorithm that exchanges messages from the links to the nodes, and from them it computes marginal

probabilities for each variable node. When the marginal probability has been found, as BP has converged, one can obtain a solution of the problem, sorting the nodes by their predicted

marginal probabilities. However, it is possible, if the graph is not locally a tree, that BP does not find a solution or converges to a random and uninformative fixed point. In these cases,

the algorithm fails. BP for graphical models runs on factor graphs where each variable node is a site of the original graph _G_(_N_, _p_), while each function node is on a link of the

original graph _G_(_N_, _p_). Here we describe briefly the main steps that we have followed in implementing AMP algorithm. For details, we refer the reader to23. AMP runs on a complete graph

described by an adjacency matrix \(\widetilde{{\mathbf{A}}}\). AMP iteratively exchanges messages from links to nodes, and from them, it computes quantities for each node. These quantities

represent the property that a variable node is, or not, in the planted set. It is intermediate in complexity and compute cost between local algorithms, such as our greedy search schemes, and

global algorithms such as the spectral methods of Alon et al.14 For our purpose, we implemented a simple version of this algorithm, using Deshpande et al’s23 equations. Here, we recall

them: $$\begin{aligned} \Gamma ^{t+1}_{i \rightarrow j}=\log \frac{K_{HC}}{\sqrt{N}}+\sum ^{N}_{l\ne i,j}\log \left( 1+\frac{(1+{\tilde{A}}_{l,i}) \text {e}^{\Gamma ^{t}_{l\rightarrow

i}}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) -\log \left( 1+\frac{\text {e}^{\Gamma ^{t}_{l\rightarrow i}}}{\sqrt{N}}\right) , \end{aligned}$$ (6) $$\begin{aligned} \Gamma ^{t+1}_{i}=\log

\frac{K_{HC}}{\sqrt{N}}+\sum ^{N}_{l\ne i}\log \left( 1+\frac{(1+{\tilde{A}}_{l,i}) \text {e}^{\Gamma ^{t}_{l\rightarrow i}}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) -\log \left( 1+\frac{\text {e}^{\Gamma

^{t}_{l\rightarrow i}}}{\sqrt{N}}\right) . \end{aligned}$$ (7) Equations (6) and (7) describe the evolution of messages and vertex quantities \(\Gamma ^{t}_{i}\). They run on a fully

connected graph, since both the presence or absence of a link between sites is described in the adjacency matrix \(\widetilde{{\mathbf{A}}}\). For numerical stability, they are written using

logarithms. Initial conditions for messages in (6) are randomly distributed and less than 0. The constant part is obtained by observing that relevant scaling for hidden clique problems is

\(\sqrt{N}\). Equation (6) describes the numerical updating of the outgoing message from site _i_ to site _j_. It is computed from all ingoing messages to _i_, obtained at the previous

iteration, excluding the outgoing message from _j_ to _i_. These messages, i.e. equation (6), are all in \(\mathbb {R}\) and they correspond to so-called odds ratios that vertex _i_ will be

in the hidden set _C_. In other words, the message from _i_ to _j_ informs site _j_ if site _i_ belongs to the hidden set or not, computing the odds ratios of all remaining \(N-2\) _l_ sites

of the graph, with \(l\ne i,j\). When a site _l_ is connected to site _i_, the difference between logarithms, in the sum, will be positive and will correspond to the event that the site _l_

is more likely to be a site of _C_ than a site outside it. However, when _l_ is not connected to _i_ the corresponding odds ratios will be less than one, i.e. the difference of logarithms,

in the sum of equation (6), will be less than zero, and will correspond to the event that the site _l_ is more likely to be outside the hidden set. The sum of all the odds ratios will update

equation (6), telling us if site _i_ is more likely to be in _C_ or not. Equation (7), instead, describes the numerical updating of the vertex quantity \(\Gamma ^{t}_{i}\). It is computed

from all ingoing messages in _i_, and is an estimation of the likelihood that \(i\in C\). These quantities are larger for vertices that are more likely to belong to the hidden clique23.

Elements of the hidden set, therefore, will have \(\Gamma ^{t_c}_{i\in C}>0\), while elements that are not in the hidden set will have \(\Gamma ^{t_c}_{i\not \in C}<0\). As iterative

BP equations, (6) and (7) are useful only if they converge. The computational complexity of each iteration is \({\mathscr {O}}(N^2)\), indeed, equation (6) can be computed efficiently using

the following observation: $$\begin{aligned} \Gamma ^{t+1}_{i \rightarrow j}=\Gamma ^{t+1}_{i}-\log \left( 1+\frac{(1+{\tilde{A}}_{j,i}) \text {e}^{\Gamma ^{t}_{j\rightarrow i}}}{\sqrt{N}}

\right) +\log \left( 1+\frac{\text {e}^{\Gamma ^{t}_{j\rightarrow i}}}{\sqrt{N}}\right) . \end{aligned}$$ (8) The number of iterations needed for convergence for all messages/vertex

quantities is of order \({\mathscr {O}}(\log N)\), which means that the total computational complexity of the algorithm is \({\mathscr {O}}(N^2 \log N)\). Once all messages in (6) converge,

the vertex quantities given by (7) are sorted into descending order. Then, the first \(K_{HC}\) components are chosen and checked to see if they are a solution. If a solution is found we

stop with a successful assignment, else the algorithm returns a failure. For completeness, our version of theAMP algorithm returns a failure also when it does not converge after \(t_{\text

{max}}=100\) iterations. As a first experiment, we run simulations, which reproduce the analysis in23, but apply their methods to a larger sample, \(N = 10^4\). In Fig. 10 we show the

fraction of successful recoveries by AMP after one convergence, as a function of \(\alpha\). As the analysis in23 predicts, the AMP messages converge down to about \(\alpha = \sqrt{N/e}\),

but with a decreasing probability of convergence, or with success in a decreasing fraction of the graphs that we have created. At and below the algorithmic threshold of AMP for this problem,

we obtained very few solutions. GREEDY SEARCH WITH EARLY STOPPING We also explored using our greedy search methods to uncover a planted clique in this difficult regime. Our hypothesis was

that using \(SM^0\) was unlikely to succeed since almost all sites selected at random do not lie within the planted clique. But \(SM^1\) seems more promising, even with its \({\mathscr

{O}}(N^3)\) cost. And if the search gave rise to any clique of size _R_(_N_) or larger, perhaps by a fixed amount \(d \ge 2\), that is strong evidence of the existence of the planted clique.

A clique of this size is a reliable starting point for a cleanup operation to find the remaining sites. The cleaning algorithm starts with a complete subgraph _C_ of order \(|C|=R(N)+2\),

obviously too large to be just any statistically generated clique. We scan the entire remaining graph, selecting the sites with the most links to the subset _C_, and adding them to _C_ to

form a subset \(C'\). The largest clique to be found in \(C'\) will add new sites not found before and may lose a few sites which did not belong. Iterating this process a few times

until no other sites can be added, in practice, gives us the hidden clique. As shown in Fig. 10, this succeeds in a greater fraction of the graphs than does AMP for planted cliques, when

\(\alpha < 1\). This strategy of stopping \(SM^1\) as soon as the hidden clique is sufficiently exposed to finish the job produces the hidden clique almost without exception in our graphs

of order \(10^4\) through the entire regime from \(\alpha = 1\) down to \(\alpha = 1/\sqrt{e}\). In this regime, AMP, converges to a solution in a rapidly decreasing fraction of the graphs.

We studied the same 100 graphs with \(\textbf{AMP}\) as were solved with \(SM^1\) at each value of \(\alpha\). Using \(SM^1\) with early stopping, we could extract planted cliques as small

as \(\alpha = 0.4\). In Fig. 11, we show the probability of success for a range of values of N. Except for the two cases for \(N = 200\) or 400, where the solutions lie close to the

naturally generated clique sizes, the success probability curves track the results obtained at \(N = 10^4\). Notice how the curves show less scatter as \(\alpha\) increases. The success of

early stopping in making \(SM^1\) useful led us to try the same with \(SM^2\). We tried this with only 5 graphs at each value of \(\alpha\), and were able to identify the planted clique in

all graphs down to \(\alpha = 0.35\), and in two out of five graphs at \(\alpha = 0.3\). The method was not successful at all at \(\alpha = 0.25\). Figure 10 compares the results of all

three methods on our test case \(N = 10^4\). It appears that the _local_, greedy methods, when used repeatedly in this fashion, are actually stronger than the more globally extended survey

data collected by AMP. But to compare their effectiveness, it is also necessary to compare their computational costs. This is explored in Fig. 12. In Fig. 12, we compare the effectiveness of

\(SM^1\) and \(SM^2\) with early stopping and AMP. First, we find that the number of trials required for \(SM^1\) to expose the hidden clique was close to _N_ at the lowest successful

searches, but dropped rapidly (the scale is logarithmic) for \(\alpha > \sqrt{1/e}\). As \(\alpha\) approaches 1, there are more starting points than there are points in the hidden

clique, while for \(\alpha < \sqrt{1/e}\), not every point in the hidden clique is an effective starting point. We briefly explored the importance of where to stop the search by running

\(SM^1\) to completion for a small number of graphs at \(\alpha = 0.6\) and considering the sizes of the cliques found. This distribution varies quite widely from one graph to another. The

full hidden clique is frequently found, and the most common size results were about half of the hidden clique size. Only a very few cliques returned by \(SM^1\) were within \(1-4\) sites of

_R_(_N_), so we recommend the stopping criterion \(R(N) + 2\) as a robust value. The average running time to solve one graph for each of the three is plotted in Fig. 12. The average cost of

solving AMP, (red points) is greatest just above \(\alpha = 1/\sqrt{e}\) where it sometimes fails to converge, and decreases at higher \(\alpha\), largely because convergence is achieved,

with fewer iterations as \(\alpha\) increases. The cost decreases at lower values of \(\alpha\) because AMP converges more quickly, but this time to an uninformative fixed point. \(SM^1\)

with early stopping (blue points) requires less time than AMP to expose the planted clique at all values of \(\alpha\) where one or both of the methods are able to succeed and is several

hundred times faster at \(\alpha = 1\). \(SM^2\) with early stopping (black points) is more expensive than \(SM^1\) with early stopping at all values of \(\alpha\), but is also less costly

than AMP in the range \(1/\sqrt{e}< \alpha <1\). It is the most costly algorithm at still lower values of \(\alpha\), but the only method that can provide any solutions down to the

present lower limit of \(\alpha = 0.3\). This efficiency, as well as the ability of local greedy algorithms with early stopping to identify cliques with \(\alpha < \sqrt{1/e}\), is a

surprising and novel result. CONCLUSIONS More than 30 years have elapsed since the DIMACS community reviewed algorithms for finding maximum cliques (and independent sets) in Erdös-Rényi

graphs _G_(_N_, _p_) with _N_ sites and bonds present with fixed probability, _p_. Computer power and computer memory roughly \(100\times\) what was available to the researchers of that

period are now found in common laptops. But unfortunately, the size of the problems that this can solve (in this area) only increases as the \(\log\) or a fractional power of the CPU speed.

We can now explore the limits of polynomial algorithms up to \(N=10^5\), while the DIMACS studies reached only a few thousand sites. In contrast to problems like random 3-SAT, for which

almost all instances have solutions by directed search2 or belief propagation-like32,33,34 methods which approach the limits of satisfiability to within a percent or less, finding a maximum

clique remains hard over a large region of parameters for almost all random graphs, if we seek solutions more than a few steps beyond \(\log _2 N\). Using tests more detailed than the

_bakeoff_ with which algorithms have been compared, we show that expensive \({\mathscr {O}}(N^3)\) and \({\mathscr {O}}(N^4)\) searches can accurately reproduce the distribution of maximum

clique sizes known to exist in fairly large random graphs. (Up to at least \(N = 500\) for the \({\mathscr {O}}(N^3)\) algorithm and about \(N = 1500\) for the \({\mathscr {O}}(N^4)\)

algorithm.) This is a more demanding and informative test of the algorithms’ performance than seeing what size clique they each can extract from graphs whose actual maximum clique size is

unknown. A more promising approach is to use the simplest search algorithm to define a subgraph much smaller than _N_ as a starting subset in which to apply the higher-order search

strategies. This does not produce the exact maximum clique, or even get within a percent or less of the answer as with SAT, because the naive initial search combines sites which belong in

different maximum cliques into the starting set. The higher-order follow-up search that we employ does not fully separate them. Therefore, from our initially defined clusters, which exceed

the \(\log _2 N\) lower bound in size, but may contain a confusing mixture of incompatible larger clusters that prevent each other from being extended we have used a restricted form of

backtracking to find the subset which is most successful in growing further. The second challenge we considered is locating and reconstructing a hidden clique. Using Deshpande and

Montanari’s23 AMP, or our slightly more than linear cost polynomial \(SM^1\) with early stopping, we can discover and reconstruct the hidden clique well below the limit of spectral methods

and almost down to the sizes of naturally occurring cliques. It is surprising that a version of the simplest greedy algorithm performs better on problems of the largest currently achievable

sizes. This is possible because the hidden clique is unique, so the greedy search is not confused. The challenges posed at the start of this paper apply only in the limit \(N \rightarrow

\infty\), in a problem with significant and interesting finite-size corrections. Although computing power, data storage, and the data from which information retrieval tools are sought to

find tightly connected communities all increase at a dramatic pace, all of these presently lie in the _finite-size_ range of interest, far from an asymptotic limit. Yet they are well beyond

the scale of previous efforts to assess algorithms for this problem. Since asymptotic behavior is only approached logarithmically in the clique problem, we think that further progress is

possible in the finite-size regime. We have shown that effective searches for cliques can be conducted on graphs of up to \(10^5\) sites, using serial programs. With better, perhaps parallel

algorithms, and the use of less-local search strategies such as AMP, can this sort of search deal with information structures of up to \(10^9\) nodes using today’s computers? With

computational resources of the next decade, and perhaps a better understanding of the nature of search in problems with such low signal-to-noise ratios as Maximum Clique, perhaps we can hope

to see graphs of order the earth’s population being handled. What we learn from looking into the details of the Overlap Gap20 (Fig. 8 and many similar plots) is that an ergodic phase in

which local rearrangements can transform any clique of size \(K_1\) into another of the same size extends slightly above \(K = \log _2 N\). But cliques of size \(K_1\) vastly outnumber

cliques of size \(K_{\text {max}}\) and the larger cliques only slightly overlap, so what is needed are efficient ways of identifying the components of such cliques with the greatest chance

of continuing to grow by local moves. Beyond the Overlap Gap, we expect to encounter a “Clustered phase” similar to that predicted for more complex systems using the arguments of replica

symmetry breaking and the calculational tools of the “cavity model”35,36. (Fortunately, the extra complications of “frozen variables,” introduced in these models, should be absent when

looking at graph properties such as Maximum Clique, where there are no extra internal degrees of freedom.) We have made progress beyond the Overlap Gap limit by simple forms of backtracking.

More expensive searches, costing higher powers of _N_, such as \(SM^1\) and \(SM^2\) are effective for a range of _N_ within this clustered phase. But stronger and more costly methods, such

as simulated annealing37 and its parallel extensions, or learning algorithms38 may be needed to provide more exhaustive search. DATA AVAILIBILITY The numerical codes used in this study and

the data that support the findings are available from the corresponding author upon request. REFERENCES * Kirkpatrick, S. & Swendsen, R. H. Statistical mechanics and disordered systems.

_Commun. ACM_ 28, 363–373 (1985). Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Selman, B. _et al._ Local search strategies for satisfiability testing. _Cliques Color. Satisfiability_ 26, 521–532

(1993). Article MATH Google Scholar * Kirkpatrick, S. & Selman, B. Critical behavior in the satisfiability of random Boolean expressions. _Science_ 264, 1297–1301 (1994). Article ADS

MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Erdös, P. & Rényi, A. On random graphs, I. _Publicationes Mathematicae (Debrecen)_ 6, 290–297 (1959). Article MathSciNet MATH Google

Scholar * Bollobás, B. _Modern Graph Theory_ (Springer, 1998). Book MATH Google Scholar * Karp, R. M. The probabilistic analysis of some combinatorial search algorithms. _Algorithms

Complex. New Dir. Recent Results_ 1, 19 (1976). Google Scholar * Matula, D. W. On the complete subgraphs of a random graph. _Combinatory Mathematics and Its Applications_ 356–369 (1970). *

Matula, D. W. Employee party problem. In _Notices of the American Mathematical Society_, vol. 19, A382–A382 (Amer Mathematical Soc 201 CHARLES ST, 1972). * Bollobás, B. & Erdös, P.

Cliques in random graphs. In _Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society_, vol. 80, 419–427 (Cambridge University Press, 1976). * Grimmett, G. R. & McDiarmid, C. J.

On colouring random graphs. In _Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society_, vol. 77, 313–324 (Cambridge University Press, 1975). * Matula, D. W. _The Largest Clique

Size in a Random Graph_ (Department of Computer Science, Southern Methodist University, 1976). Google Scholar * Johnson, D. S. & Trick, M. A. _Cliques, Coloring, and Satisfiability:

Second DIMACS Implementation Challenge, October 11–13, 1993_, vol. 26 (American Mathematical Soc., 1996). * Jerrum, M. Large cliques elude the metropolis process. _Random Struct. Algorithms_

3, 347–359 (1992). Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Alon, N., Krivelevich, M. & Sudakov, B. Finding a large hidden clique in a random graph. _Random Struct. Algorithms_ 13,

457–466 (1998). Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Dekel, Y., Gurel-Gurevich, O. & Peres, Y. Finding hidden cliques in linear time with high probability. _Combinatorics Prob.

Comput._ 23, 29–49 (2014). Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Brockington, M. & Culberson, J. C. Camouflaging independent sets in quasi-random graphs. _Cliques Color.

Satisfiability Second DIMACS Implement. Challenge_ 26, 75–88 (1996). Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Kučera, L. A generalized encryption scheme based on random graphs. In

_International Workshop on Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science_, 180–186 (Springer, 1991). * Panneton, F., L’ecuyer, P. & Matsumoto, M. Improved long-period generators based on

linear recurrences modulo 2. _ACM Trans. Math. Softw._ 32, 1–16 (2006). Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Feller, W. _An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications_

Vol. 1 (Wiley, 1968). MATH Google Scholar * Gamarnik, D. The overlap gap property: A topological barrier to optimizing over random structures. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 118, e2108492118

(2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kučera, L. Expected complexity of graph partitioning problems. _Discret. Appl. Math._ 57, 193–212 (1995). Article MathSciNet

MATH Google Scholar * Sanchis, L. A. Test case construction for the vertex cover. In _Computational Support for Discrete Mathematics: DIMACS Workshop, March 12-14, 1992_, vol. 15, 315

(American Mathematical Soc., 1994). * Deshpande, Y. & Montanari, A. Finding hidden cliques of size \(\sqrt{N/e}\) in nearly linear time. _Found. Comput. Math._ 15, 1069–1128 (2015).

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Angelini, M. C. Parallel tempering for the planted clique problem. _J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp._ 2018, 073404 (2018). Article MathSciNet MATH

Google Scholar * Angelini, M. C. & Ricci-Tersenghi, F. Monte Carlo algorithms are very effective in finding the largest independent set in sparse random graphs. _Phys. Rev. E_ 100,

013302. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.100.013302 (2019). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Montanari, A., Ricci-Tersenghi, F. & Semerjian, G. Solving constraint

satisfaction problems through belief propagation-guided decimation. _arXiv preprint_ arXiv:0709.1667 (2007). * Felzenszwalb, P. F. & Huttenlocher, D. P. Efficient belief propagation for

early vision. _Int. J. Comput. Vis._ 70, 41–54 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Yedidia, J. S., Freeman, W. T. & Weiss, Y. Generalized belief propagation. In _Advances in Neural

Information Processing Systems_, 689–695 (2001). * Mezard, M. & Montanari, A. _Information, Physics, and Computation_ (Oxford University Press, 2009). Book MATH Google Scholar * Frey,

B. J. & MacKay, D. J. A revolution: Belief propagation in graphs with cycles. In _Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems_, 479–485 (1998). * Mooij, J. M. & Kappen, H. J.

Sufficient conditions for convergence of loopy belief propagation. In _Proceedings of the Twenty-First Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence_, 396–403 (AUAI Press, 2005). *

Mézard, M., Parisi, G. & Zecchina, R. Analytic and algorithmic solution of random satisfiability problems. _Science_ 297, 812–815 (2002). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Mézard,

M. & Montanari, A. _Constraint Satisfaction Networks in Physics and Computation_ Vol. 1, 11 (Clarendon Press, 2007). Google Scholar * Marino, R., Parisi, G. & Ricci-Tersenghi, F.

The backtracking survey propagation algorithm for solving random \(\text{ K-SAT }\) problems. _Nat. Commun._ 7, 12996 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Krzakała, F., Montanari, A., Ricci-Tersenghi, F., Semerjian, G. & Zdeborová, L. Gibbs states and the set of solutions of random constraint satisfaction problems. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._

104, 10318–10323 (2007). Article ADS MathSciNet PubMed MATH Google Scholar * Zdeborová, L. Statistical physics of hard optimization problems. _arXiv preprint_ arXiv:0806.4112 (2008).

* Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by simulated annealing. _Science_ 220, 671–680 (1983). Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar *

Bengio, Y., Lodi, A. & Prouvost, A. Machine learning for combinatorial optimization: A methodological tour d’horizon. _Eur. J. Oper. Res._ 290, 405–421 (2021). Article MathSciNet MATH

Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS RM and SK were supported by the Federman Cyber Security Center of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Continued collaboration was

hosted at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”, and at the MIT Media Lab. We enjoyed stimulating conversations with Federico Ricci-Tersenghi and Maria Chiara Angelini. RM thanks the FARE

grant No. R167TEEE7B and the grant “A multiscale integrated approach to the study of the nervous system in health and disease (MNESYS)”. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS *

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università degli studi di Firenze, Via Giovanni Sansone, 1, 50019, Sesto Fiorentino, FI, Italy Raffaele Marino * Dipartimento di Fisica, Sapienza

Università di Roma, P.le Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Roma, Italy Raffaele Marino * School of Computer Science and Engineering, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Edmond Safra Campus, Givat Ram,

91904, Jerusalem, Israel Raffaele Marino & Scott Kirkpatrick Authors * Raffaele Marino View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Scott

Kirkpatrick View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS All authors contributed to all aspects of this work. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Raffaele Marino. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains

neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Marino, R., Kirkpatrick, S. Hard optimization problems have soft edges. _Sci

Rep_ 13, 3671 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30391-8 Download citation * Received: 18 September 2022 * Accepted: 22 February 2023 * Published: 04 March 2023 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30391-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

Boris johnson’s brexit tax cuts plea rejected by theresa mayIncome tax, stamp duty and capital gains tax should all be reduced without rises in other levies, Mr Johnson said. His c...

How to sell your home to foreignersWHETHER it is a country house or a town flat, a property that has huge appeal to a Briton might not appeal at all to a F...

Government has 'absolutely no plans' to scrap free bus passThe UK Government has "absolutely no plans to withdraw the concessionary bus pass scheme" for those over State...

Great read: with ingenuity and a 3-d printer, group changes livesMick Ebeling arrived in Sudan with little more than a toolbox, rolls of plastic and two microwave-size 3-D printers. He ...

New government envoy for the year of engineering announcedNews story NEW GOVERNMENT ENVOY FOR THE YEAR OF ENGINEERING ANNOUNCED Stephen Metcalfe MP will drive cross-government su...

Latests News

Hard optimization problems have soft edgesABSTRACT Finding a Maximum Clique is a classic property test from graph theory; find any one of the largest complete sub...

Awesome article, this isn't the easiest skill to master, but once it IS mastered, leaders and their teams really do become unstoppable. Thank you forTony HunterFollowMar 17, 2021 --ListenShareAwesome article, this isn't the easiest skill to master, but once it IS maste...

Jimmy fallon introduces julia roberts to 'face balls'Jimmy Fallon plays a lot of games on “The Tonight Show,” but to keep things fresh, he can’t just play the same game over...

27 lakh people visited Kolkata Book Fair 2025Newsletters ePaper Sign in HomeIndiaKarnatakaOpinionWorldBusinessSportsVideoEntertainmentDH SpecialsOperation SindoorNew...

Boeing to buy more 737 max simulators as airlines eye training rushBoeing (BA) is buying more 737 Max simulators as airlines around the world face a scramble to train their pilots so the ...