Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted lambdoid craniosynostosis correction

Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted lambdoid craniosynostosis correction"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Download PDF Article Open access Published: 29 October 2020 Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted lambdoid craniosynostosis correction Selim Bozkurt1,2, Alessandro

Borghi2,3, Lara S. van de Lande2,3, N. U. Owase Jeelani2,3, David J. Dunaway2,3 & …Silvia Schievano2,3 Show authors Scientific Reports volume 10, Article number: 18693 (2020) Cite this

article

2939 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Subjects Bone developmentBone remodellingComputational science AbstractLambdoid craniosynostosis (LC) is a rare non-syndromic craniosynostosis characterised by fusion of the lambdoid sutures at the back of the head. Surgical correction including the spring

assisted cranioplasty is the only option to correct the asymmetry at the skull in LC. However, the aesthetic outcome from spring assisted cranioplasty may remain suboptimal. The aim of this

study is to develop a parametric finite element (FE) model of the LC skulls that could be used in the future to optimise spring surgery. The skull geometries from three different LC patients

who underwent spring correction were reconstructed from the pre-operative computed tomography (CT) in Simpleware ScanIP. Initially, the skull growth between the pre-operative CT imaging and

surgical intervention was simulated using MSC Marc. The osteotomies and spring implantation were performed to simulate the skull expansion due to the spring forces and skull growth between

surgery and post-operative CT imaging in MSC Marc. Surface deviation between the FE models and post-operative skull models reconstructed from CT images changed between ± 5 mm over the skull

geometries. Replicating spring assisted cranioplasty in LC patients allow to tune the parameters for surgical planning, which may help to improve outcomes in LC surgeries in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others Spring-assisted posterior vault expansion: a parametric study to improve the intracranial volume increase prediction Article Open access 04 December

2023 Predicting and comparing three corrective techniques for sagittal craniosynostosis Article Open access 27 October 2021 Allometry of human calvaria bones during development from birth to

8 years of age shows a nonlinear growth pattern Article Open access 31 October 2024 Introduction

Lambdoid craniosynostosis (LC) is a rare type of craniosynostosis where the lambdoid sutures are fused1,2,3. It can take place in bilateral or unilateral form or may even exist along with

other types of cranial deformities4, and is associated with herniated cerebellar tonsils5. Fused lambdoid sutures in an LC skull cause shape asymmetry in the back of the skull, which may in

turn result in further problems, such as raised intracranial pressure or torticollis because of developing positioning preference and shortening of the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid

muscle6,7. Surgical intervention is the only treatment to expand the cranial vault in LC and thus correct the asymmetry in the skull8. Different surgical approaches such as endoscopic strip

suturectomy, bone flap remodelling or switching, distraction osteogenesis or spring assisted correction may be adopted to correct the deformity9,10,11,12,13,14, usually before 12 months of

age15. Nonetheless, aesthetic outcomes of the surgical correction in LC generally remain suboptimal, with persisting asymmetry at the cranial base and posterior cranial vault16.

Springs were first used at Sahlgrenska University Hospital to correct cranial vault postoperatively17,18. Spring assisted cranioplasty is performed mainly to correct scaphocephaly, the most

common craniosynostosis type19,20, but also for patients with a brachycephalic head shape due to (bi) coronal craniosynostosis by performing a posterior vault expansion. Modifications have

been introduced for head shape correction in anterior plagiocephaly and metopic synostosis21,22,23. Spring assisted correction of lambdoid craniosynostosis has been reported, where it was

part of a multi-sutural deformity24,25. The surgery requires insertion of spring distractors in the skull after osteotomies are performed to release the fused sutures; the springs, initially

compressed, start opening resulting in an expansion force to the skull perpendicular to the osteomised cranial bone. Although spring assisted cranioplasty requires a second operation to

remove the devices26, it has the advantages of providing increase in volume and circumference of the cranium, whilst being minimally invasive, thus reducing procedural morbidity and

requiring relatively short operative time and hospital stay23,26,27.

Understanding the 3D asymmetry in spring assisted LC correction or simulating the treatment using a patient-specific skull model may help improve the outcome of this procedure. Finite

element (FE) analyses have already been utilised to simulate correction of cranial deformities. For instance, Wolanski et al. focused on sagittal and metopic craniosynostosis correction28;

Borghi et al. simulated spring assisted correction of sagittal craniosynostosis in patient-specific models29; Malde et al. developed a patient-specific FE model of sagittal craniosynostosis

to predict calvarial morphology30; and Bozkurt et al. evaluated potential correction methods for unicoronal craniosynostosis using a patient-specific FE skull model31. Numerical studies

aiming to simulate skull correction focus on common craniosynostosis types such as sagittal, unicoronal or metopic synostosis. Therefore, simulation of isolated LC correction remains to

study.

The aim of this study is to simulate spring assisted correction in isolated LC patients using patient-specific skull models via parametric FE analyses which can provide useful insights to

improve the outcome of spring assisted cranioplasty.

MethodsData was analysed in accordance with the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained for the collection, storage and analysis of the tissue samples (UK

REC 09/H0722/28) and use of image data for research purposes (UK REC 15/LO/0386) from the Joint Research and Development Office of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. All

parents/guardians gave written informed consent to participate in this study.

Three LC patients who underwent spring assisted surgery for abnormal skull shape at our Craniofacial Unit with pre- and post-operative computed tomography (CT) images were selected for this

study. The patients were 196 (patient 1), 134 (patient 2) and 104 (patient 3) days old at time of pre-operative CT scan imaging; they underwent surgery at 242, 196 and 199 days of age; and

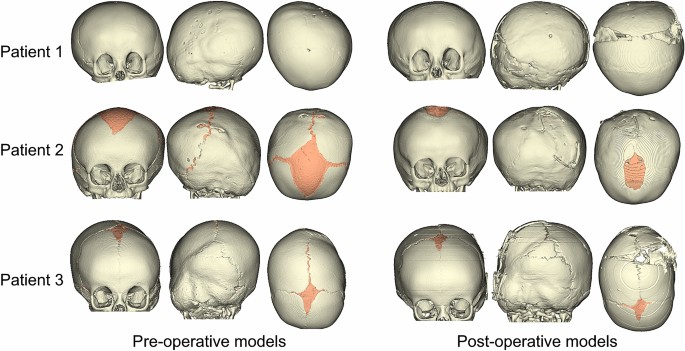

the post-operative scans were acquired at the age of 317, 420 and 210 days, respectively. Patient specific skull models were reconstructed from the CT images in Simpleware ScanIP, including

the bone of the calvarium to the maxilla and the suture structures. The pre- and post-operative patient specific reconstructions are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1Patient-specific pre and post-operative skull models reconstructed from the CT images.

Full size imageStructural 3D tetrahedral elements were used to mesh and create the skull FE models (354,359, 672,269 and 574,283 in each model, respectively). Materials were modeled as linear elastic with

Poisson ratio (ν) equal to 0.49 for the sutures and 0.22 for the bony parts, whilst the Elastic modulus (E) was selected according to the patient age. Validated parametric FE models showed

that average Elastic modulus of skull bone in 0–9 month old children is around 157 MPa and for sutures 8.3 MPa32,33. However, these values change significantly with age34. Therefore, Elastic

modulus of the bony part was selected as 157 MPa for the first model and 85 MPa for the other two models considering the age of the patients at the intra-operative time. Elastic modulus of

the sutures was 8.3 MPa for all patients. Fixed nodal displacement and rotation boundary conditions were applied at the base of the models.

Exponential increase in skull size results in a high growth rate in intracranial volume (ICV) during the first 12 months of life and in a significantly reduced growth rate after 5 years of

age35. Therefore, skull growth between the pre-operative CT imaging and surgical intervention time was simulated in the FE package MSC Marc before performing the osteotomies on the skull

models. ICV was used as the parameter representing skull size as described in36. ICV at time of surgery was estimated utilising an empirical model37 which predicts the skull growth until 18

years of age as

$$ {\text{ICV}}_{{\text{h}}} \;({\text{t}}) = 157.9\;{\ln}({\text{t}}) + 104.1. $$ (1)Here, ICVh represents the ICV in healthy subjects and t represents time. Surgical intervention in LC skulls is generally performed before 12 months of age, as in the analysed patients15.

Therefore, a small portion of the curve covering the times between pre-operative CT imaging and surgical intervention was used to predict skull growth in the simulations, as shown in Fig.

2.

Figure 2Intracranial volume (ICV) simulated by the model in Eq. (1) and region of interest on the growth curve with representative pre-operative, surgical intervention and post-operative

times.

Full size imageICV growth in the LC patients was assumed proportional to ICV growth of healthy subjects. A coefficient (k) describing the ratio between ICV in LC patients (ICVLC,pre) and ICV in healthy

subjects (ICVLC,pre) was defined as:

$$ {\text{k}}\, = \frac{{{\text{ICV}}_{{\text{LC,pre}}} ({\text{t}})}}{{{\text{ICV}}_{{\text{h,pre}}} ({\text{t}})\,}}. $$ (2)Thus, intra-operative ICV (ICVLC,intra) at time of surgery in the LC skull models was estimated for each patient as.

$$ {\text{ICV}}_{{\text{LC,intra}}} ({\text{t}})\, = {\text{k}} \times{\text{ICV}}_{{\text{h,intra}}} ({\text{t}}). $$ (3)

Skull growth between the pre-operative CT scan and surgical intervention was implemented for each model in MSC Marc using a similar method to that proposed by Libby et al.38 who approximated

skull growth to a thermal expansion as

$$ {\text{V}}_{{\text{LC,intra}}} - {\text{V}}_{{\text{LC,pre}}} = {\text{V}}_{{\text{LC,pre}}} \times \alpha \times \Delta {\text{T}}. $$ (4)Here, V represents size of the bony and soft tissue parts of the skull, α is the expansion coefficient and ΔT is the temperature difference.

The ICV was measured from the pre-operative CT reconstructions by selecting the internal surface of the cranial vault in Simpleware ScanIP.

The osteotomies on the skulls performed at the time of surgery were replicated on the skull geometries after reaching the intra-operative estimated ICV by following the traces remaining

visible from the surgery on the post-operative skull models in Simpleware ScanIP. The skull geometries with osteotomies were re-meshed using structural 3D tetrahedral elements (450,744,

782,668 and 767,282 for patient 1, 2 and 3, respectively). Spring implantation was simulated using spring/dashpot link elements in MSC Marc, by specifying spring stiffness (1.2 mm wire

diameter springs were used in Patient 1, and 1.4 mm wire diameter in Patient 2 and Patient 3) and initial force in a compressed spring according to the characteristics reported in39. The

skull growth between surgical intervention and post-operative CT scan was simulated using the methods described in Eq. (4). The temperature difference (ΔT) was 100 K in all pre and

post-operative FE models. The FE models with osteotomies and springs are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3The FE models simulating spring assisted cranial expansion with osteotomies.

Full size imageSurface deviation between the expanded FE skull models and post-operative CT skull reconstructions was assessed in Simpleware ScanIP, after volume registration achieved using landmarks on

the anterior nasal spine and frontozygomatic sutures, not affected by the surgery40. Simulations were performed iteratively by tuning the expansion coefficients (α) until the average surface

distance was within ± 1 mm of the post-operative CT reconstructions for all cases and the average negative and positive surface deviations were between − 1 mm and + 1 mm respectively for

the entire skull in each model.

ResultsShapes of the intracranial cavities at the time of pre-operative CT in each patient are given in Fig. 4. Premature fusion of the lambdoid suture creates flattening in the posterior skull and

deformities due to LC are also noticeable in the intracranial geometries of the patients (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Shapes of the intracranial cavities in the patients’ skulls.

Full size imageThe tuned expansion coefficients used in the thermal FE models simulating skull growth between the pre-operative CT scans and surgical intervention are given in Table 1. Pre-operative ICV

measured from CT, and ICV at the time of surgery estimated from growth curve and simulated in the FE models are reported in Table 1. The FE values match well the intraoperative ICV volumes.

Patient 1 had the largest pre and intra-operative ICVs among all the patients whilst a relatively small expansion coefficient was used to simulate skull growth in it. Although, Patient 2 and

Patient 3 had similar pre-operative ICVs, Patient 3 had a larger intra-operative skull size.

Table 1 Thermal expansion coefficients pre-operative ICV, estimated and simulated ICVs in theFE models simulating skull growth between pre-operative CT scans and surgical interventions.Full size table

Displacement maps for the FE models simulating the skull growth between the pre-operative CT scan and surgical intervention are given in Fig. 5. Maximal displacements in the skull models of

Patient 1, Patient 2 and Patient 3 were 1.49 mm, 2.55 mm and 5.10 mm, respectively. Relatively high displacements are achieved in the Patient 3 skull model due to relatively young age,

therefore, a higher expansion coefficient used in the simulations to achieve the estimated intra-operative ICV.

Figure 5Displacement maps for the FE models simulating the skull growth between the pre-operative CT scan and surgical intervention.

Full size imageSurface deviations between the FE models and post-operative skull models reconstructed from CT images are given in Fig. 6. Surface deviation was relatively low on the frontal and temporal

bones, and increased on the posterior skull surfaces expanded by the springs. In particular, the highest values of surface deviations were recorded on the top portion of the posterior flap

of Patient 1 and Patient 3. The cross-sections of the FE models simulating spring assisted cranioplasty and post-operative skull growth (orange), and the post-operative CT reconstructions

(black) are shown in Fig. 7. The surface deviation of the superior portion of the skull between FE and post-op CT is visible for Patient 1 and slightly less for Patient 3. The FE model and

post-operative model of Patient 2 matched fairly well with a slight deviation at the inferior portion of the skull.

Figure 6Surface deviation between the FE models and post-operative skull models reconstructed from CT images.

Full size imageFigure 7Comparison between the cross-sections of the FE models simulating spring assisted cranioplasty (orange) and post-operative skull growth and post-operative skull models reconstructed from CT

images (black).

Full size imageThe thermal expansion coefficients in the FE models simulating spring assisted correction skull growth between surgical interventions and post-operative CT scans are given in Table

2.

Table 2 Thermal expansion coefficients and post-operative ICV in the FE models simulating spring assisted correction and skull growth between surgical interventions and post-operativeCT scans.Full size table

Although a relatively high expansion coefficient was used in the Patient 2 FE model, the increase in the skull size remained relatively small. On the other hand, there was a remarkable

increase in the ICV of patient 3 due spring assistance, although a very small thermal expansion coefficient was used in the simulations. The surgery resulted in expansion of the posterior

vault of the skull in Patient 1 and Patient 3, whilst for Patient 2, the operation increased mainly the width of the osteotomy rather than the overall skull.

Displacement maps for the skull models for the spring assisted cranioplasty and post-operative skull growth are given in Fig. 8. Maximal displacements in the skull models of Patient 1,

Patient 2 and Patient 3 were 23.55 mm, 14.33 and 40.01 mm, respectively, with Patient 3 having the largest displacements overall.

Figure 8Displacement maps for the skull models for the spring assisted cranioplasty and post-operative skull growth.

Full size imageDiscussionIn this study, spring assisted cranioplasty was simulated for isolated LC using FE analyses in three different patient specific models. Skull growth between the pre-operative CT imaging and

surgical intervention, and after surgical intervention was included in the simulations. The simulation results were validated using post-operative reconstructions from CT images.

Brain growth in infants is driven by biological and genetic mechanisms41, and the skull grows in synchrony with the brain42,43 through extremely complex signaling pathways and genetic

mutations. Interaction between different mechanisms still remains unclear in patients affected by craniosynostosis whereas regulatory mechanisms are extremely complex44. Moreover, recent

studies suggest that skull growth patterns in craniosynostosis depend on mechanical effects45. Therefore, developing a model simulating skull growth remains a challenge. In this study, skull

growth was simulated using a relatively simple model similar to thermal expansion, where the amount of skull growth depends on a thermal expansion coefficient, and is driven by a

temperature difference, constant across all patient models. The expansion coefficient is tuned for each individual skull FE model: higher expansion coefficients are used when the patient is

younger or when there is a longer time span between the pre-operative CT imaging and surgical intervention, or surgical intervention and post-operative CT imaging. The skull growth rate in

each patient was personalised through a proportional coefficient (k) based on the patient pre-operative ICV and the growth curve developed by Breakey et al.37 for healthy children.

Relatively high “k” values representing large LC patient intracranial volumes will result in a faster growth rate as “k” is multiplied also with the term including time (Eq. 3) whereas

relatively small “k” values will result in a slower growth rate.

The structure of the cranial bones is not homogenous due to very complex developmental mechanisms in the skull44 ; therefore, in children, the properties change substantially with age34 and

are different in the different parts of the skull34. In this study, the bones and sutures were assumed homogenous and with the same mechanical behavior for every bony portion as data are not

available for the specific patient populations. Although, relatively high elastic modulus values are reported in the literature for cranial bones34, the spring assisted cranioplasty FE

simulations with selected low values for the material properties, were in good agreement with the post-operative CT scans. Reason for the difference of the material properties could be that

the non-homogenous structure of the bones may result in higher elastic modulus values whereas a similar mechanical response from a homogenous material could be obtained with a relatively low

elastic modulus value. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the selected values for the material properties are within a biological range for the ages of simulated patients32,33,34.

The simulation results in this study show that the final shape of the skull depends on the performed osteotomies. Relatively longer cuts as performed in Patient 1 and Patient 3 allow mainly

hinging and expansion in the cranium whereas a minimal cut as in Patient 2 allows the gap between edges of osteotomy to enlarge. It has already been shown that the size and locations of the

osteotomies are crucial for an optimal outcome from surgical operations31. The simulation results in this study confirm the findings in the literature.

Although the surface deviation between the FE models and post-operative skull models constructed from CT images remained within a low range, it was relatively high at the back side where the

skull was expanded in Patient 1 and Patient 3. Relatively high surface deviations might be because of the complex mechanical properties of cranial bones, such as viscoelasticity, are not

included in the simulations.

The spring assisted cranioplasty FE models in this study was simulated by including skull growth and mechanical properties of the bones and sutures (i.e. modulus and passion ratio).

Simulating the viscoelastic properties of the cranial bones in the future will allow remodeling of the skull during recovery as a result of mechanical adaptation under spring force46.

Moreover, properties of bones change over time, therefore, modelling these changes with respect to age rather than modifying only the expansion coefficients for every operation will allow

simulating and planning the surgical intervention more accurately. The skull growth in the patient models was evaluated by adapting the healthy subject curve of change of ICV over time (Fig.

2)37. Isolated LC is a highly rare syndrome; therefore, a model that can predict the skull growth in these specific patients requires is not yet available. Sutures are the fibrous tissues

in between the cranial bones and facilitate the cranial growth47. Moreover, they generate bone at edges of the bones by responding the external stimuli47. Understanding of this mechanism is

still limited48; therefore bone formation is not included in the FE models. Nonetheless, it should be noted that despite the limitations, the developed FE models simulated spring assisted

cranioplasty in the LC patients accurately.

ConclusionsThe simulation results show the potential of the parametric FE models to simulate surgical outcomes in LC corrected with spring assisted cranioplasty. Replicating spring assisted

cranioplasty in LC patients allow tuning of the parameters for surgical planning. Larger studies would allow to determine a population specific set of parameters for these patients in order

to use the model prospectively. A parametric study on spring types and locations could then allow optimisation of function and aesthetic outcomes in LC surgical corrections.

Dataavailability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References David, D. J. & Menard, R. M. Occipital plagiocephaly. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 53, 367–377 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Boulet, S. L., Rasmussen, S. A. & Honein, M. A. A population-based study of craniosynostosis in metropolitan Atlanta, 1989–2003. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 146A, 984–991 (2008).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Borad, V. et al. Isolated lambdoid craniosynostosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 30, 2390–2392 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rhodes, J. L., Tye, G. W. & Fearon, J. A. Craniosynostosis of the lambdoid suture. Semin. Plast. Surg. 28, 138–143 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ghizoni, E. et al. Diagnosis of infant synostotic and nonsynostotic cranial deformities: a review for pediatricians. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 34, 495–502 (2016).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Orra, S. et al. The danger of posterior plagiocephaly. Eplasty 15, ic26 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Biggs, W. S. Diagnosis and management of positional head deformity. Am. Fam. Physician 67, 1953–1956 (2003).

PubMed Google Scholar

Wilbrand, J.-F., Howaldt, H.-P., Reinges, M. & Christophis, P. Surgical correction of lambdoid synostosis—new technique and first results. J. Cranio-Maxillo-fac. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Assoc.

Cranio-Maxillo-fac. Surg. 44, 1531–1535 (2016).

Google Scholar

Jimenez, D. F., Barone, C. M., Cartwright, C. C. & Baker, L. Early management of craniosynostosis using endoscopic-assisted strip craniectomies and cranial orthotic molding therapy.

Pediatrics 110, 97–104 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cartwright, C. C., Jimenez, D. F., Barone, C. M. & Baker, L. Endoscopic strip craniectomy: a minimally invasive treatment for early correction of craniosynostosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. J. Am.

Assoc. Neurosci. Nurses 35, 130–138 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Elliott, R. M., Smartt, J. M., Taylor, J. A. & Bartlett, S. P. Does conventional posterior vault remodeling alter endocranial morphology in patients with true lambdoid synostosis?. J.

Craniofac. Surg. 24, 115–119 (2013).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Liu, Y. et al. The misdiagnosis of craniosynostosis as deformational plagiocephaly. J. Craniofac. Surg. 19, 132–136 (2008).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Komuro, Y. et al. Treatment of unilateral lambdoid synostosis with cranial distraction. J. Craniofac. Surg. 15, 609–613 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Arnaud, E., Marchac, A., Jeblaoui, Y., Renier, D. & Di Rocco, F. Spring-assisted posterior skull expansion without osteotomies. Childs Nerv. Syst. 28, 1545–1549 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Al-Jabri, T. & Eccles, S. Surgical correction for unilateral lambdoid synostosis: a systematic review. J. Craniofac. Surg. 25, 1266–1272 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Zubovic, E. et al. Cranial base and posterior cranial vault asymmetry after open and endoscopic repair of isolated lambdoid craniosynostosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 26, 1568–1573 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lauritzen, C., Sugawara, Y., Kocabalkan, O. & Olsson, R. Spring mediated dynamic craniofacial reshaping. Case report. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Hand Surg. 32, 331–338 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lauritzen, C., Davis, C., Ivarsson, A., Sanger, C. & Hewitt, T. The evolving role of springs in craniofacial surgery: the first 100 clinical cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 121, 545–554

(2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arko, L. et al. Spring-mediated sagittal craniosynostosis treatment at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: technical notes and literature review. Neurosurg. Focus 38, E7 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

van Veelen, M.-L.C. et al. Minimally invasive, spring-assisted correction of sagittal suture synostosis: technique, outcome, and complications in 83 cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 141,

423–433 (2018).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Tovetjärn, R. C. J. et al. Intracranial volume in 15 children with bilateral coronal craniosynostosis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2, e243 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shen, W. et al. Piezosurgical suturectomy and sutural distraction osteogenesis for the treatment of unilateral coronal synostosis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 3, e475 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

de Jong, T., van Veelen, M. L. C. & Mathijssen, I. M. J. Spring-assisted posterior vault expansion in multisuture craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv. Syst. ChNS Off. J. Int. Soc. Pediatr.

Neurosurg. 29, 815–820 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

Costa, M. A. et al. Spring-assisted cranial vault expansion in the setting of multisutural craniosynostosis and anomalous venous drainage: case report. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 16, 80–85

(2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

O’Hara, J. et al. Syndromic craniosynostosis: complexities of clinical care. Mol. Syndromol. 10, 83–97 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Rodgers, W. et al. Spring-assisted cranioplasty for the correction of nonsyndromic scaphocephaly: a quantitative analysis of 100 consecutive cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 140, 125–134

(2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pearson, A. & Matava, C. T. Anaesthetic management for craniosynostosis repair in children. BJA Educ. 16, 410–416 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Wolański, W., Larysz, D., Gzik, M. & Kawlewska, E. Modeling and biomechanical analysis of craniosynostosis correction with the use of finite element method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed.

Eng. 29, 916–925 (2013).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Borghi, A. et al. Spring assisted cranioplasty: a patient specific computational model. Med. Eng. Phys. 53, 58–65 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Malde, O., Libby, J. & Moazen, M. An overview of modelling craniosynostosis using the finite element method. Mol. Syndromol. 10, 74–82 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bozkurt, S., Borghi, A., Jeelani, O., Dunaway, D. & Schievano, S. Computational evaluation of potential correction methods for unicoronal craniosynostosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 31, 692–696

(2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Li, Z., Zhang, J. & Hu, J. Surface material effects on fall-induced paediatric head injuries: a combined approach of testing, modelling and optimisation. Int. J. Crashworthiness 18, 371–384

(2013).

Article Google Scholar

Li, Z., Liu, W., Zhang, J. & Hu, J. Prediction of skull fracture risk for children 0–9 months old through validated parametric finite element model and cadaver test reconstruction. Int. J.

Legal Med. 129, 1055–1066 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Coats, B. & Margulies, S. S. Material properties of human infant skull and suture at high rates. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1222–1232 (2006).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dekaban, A. S. Tables of cranial and orbital measurements, cranial volume, and derived indexes in males and females from 7 days to 20 years of age. Ann. Neurol. 2, 485–491 (1977).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Breakey, W. et al. Intracranial volume measurement: a systematic review and comparison of different techniques. J. Craniofac. Surg. 28, 1746–1751 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Breakey, R. W. et al. Intracranial volume and head circumference in children with unoperated syndromic craniosynostosis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 142, 708e–717e (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Libby, J. et al. Modelling human skull growth: a validated computational model. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170202 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borghi, A. et al. Assessment of spring cranioplasty biomechanics in sagittal craniosynostosis patients. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 20, 400–409 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Caversaccio, M., Zulliger, D., Bächler, R., Nolte, L. P. & Häusler, R. Practical aspects for optimal registration (matching) on the lateral skull base with an optical frameless

computer-aided pointer system. Am. J. Otol. 21, 863–870 (2000).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

van Dyck, L. I. & Morrow, E. M. Genetic control of postnatal human brain growth. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 30, 114–124 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Richtsmeier, J. T. et al. Phenotypic integration of neurocranium and brain. J. Exp. Zoolog. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 306B, 360–378 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

Nieman, B. J., Blank, M. C., Roman, B. B., Henkelman, R. M. & Millen, K. J. If the skull fits: magnetic resonance imaging and microcomputed tomography for combined analysis of brain and

skull phenotypes in the mouse. Physiol. Genomics 44, 992–1002 (2012).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Flaherty, K., Singh, N. & Richtsmeier, J. T. Understanding craniosynostosis as a growth disorder. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 5, 429–459 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Weickenmeier, J., Fischer, C., Carter, D., Kuhl, E. & Goriely, A. Dimensional, geometrical, and physical constraints in skull growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 248101 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Ou Yang, O. et al. Analysis of the cephalometric changes in the first 3 months after spring-assisted cranioplasty for scaphocephaly. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS 70, 673–685

(2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Opperman, L. A. Cranial sutures as intramembranous bone growth sites. Dev. Dyn. 219, 472–485 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Marghoub, A. et al. Characterizing and modeling bone formation during mouse calvarial development. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 048103 (2019).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

AcknowledgementsThe work has been funded by Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children Charity (Grant number 12SG15), the NIHR GOSH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre Advanced Therapies for Structural

Malformations and Tissue Damage pump-prime funding call (Grant number 17DS18), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/N02124X/1) and the European Research Council

(ERC-2017-StG-757923). This report incorporates independent research from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre Funding Scheme. The views expressed in this

publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Author informationAuthors and Affiliations Institute of Cardiovascular Science, University College London, London, UK

Selim Bozkurt

University College London, Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK

Selim Bozkurt, Alessandro Borghi, Lara S. van de Lande, N. U. Owase Jeelani, David J. Dunaway & Silvia Schievano

Craniofacial Unit, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, UK

Alessandro Borghi, Lara S. van de Lande, N. U. Owase Jeelani, David J. Dunaway & Silvia Schievano

AuthorsSelim BozkurtView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Alessandro BorghiView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Lara S. van de LandeView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

N. U. Owase JeelaniView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

David J. DunawayView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Silvia SchievanoView author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

ContributionsS.B designed the study and performed the work; A.B., L.S.L., N.U.O.J., D.J.D. and S.S. contributed writing, reviewing and editing of the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author Correspondence to Selim Bozkurt.

Ethics declarations Competing interestsThe authors declare no competing interests.

Additional informationPublisher's noteSpringer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissionsOpen Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or

format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or

other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in

the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the

copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this articleCite this article Bozkurt, S., Borghi, A., van de Lande, L.S. et al. Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted lambdoid craniosynostosis correction. Sci

Rep 10, 18693 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75747-6

Download citation

Received: 23 June 2020

Accepted: 19 October 2020

Published: 29 October 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75747-6

Share this article Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by Spring-assisted posterior vault expansion: a parametric study to improve the intracranial volume increase prediction Lara DeliègeKaran Ramdat MisierAlessandro Borghi

Scientific Reports (2023)

Trending News

Safemoon price live: how does safemoon compare to dogecoin today?But people should be aware investments in SafeMoon can go up and down, and anyone considering investing should be aware ...

New Look 'flattering and comfy' £34 midi dress shoppers have 'bought in 3 colours'New Look 'flattering and comfy' £34 midi dress shoppers have 'bought in 3 colours'The best-selling shirt dress comes in ...

Nursing home dumping - preventing resident dumping“Resident dumping” — when a nursing facility discharges a resident and refuses to readmit them after a hospital stay or ...

Fate & fabled | what constellations mean to different cultures | season 1 | episode 4When you look up at the night sky, what do you see? Maybe it looks like a random smattering of dim lights. Or perhaps yo...

Hard schedule comes amid hard timesThe calendar indicates it’s time for the Clippers to get their act together. The schedule indicates it’s going to be dif...

Latests News

Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted lambdoid craniosynostosis correctionDownload PDF Article Open access Published: 29 October 2020 Computational modelling of patient specific spring assisted ...

Reporters without orders ep 245: gujarat polls, ed summons to hemant sorenThis week, host Basant Kumar is joined by Rajnish Kumar of _BBC Hindi _and _Hindustan_ journalist Akhilesh Singh. Akhile...

‘The Media Is Failing To Generate A More Informed Debate On Black Money’Journalist and film maker Noopur Tiwari has reported extensively on the black money story. Based in France, she is the o...

Nl interview: kabir bedi on his autobiography, interviewing the beatles, and cinema cultureIn this episode of NL Recess, actor Kabir Bedi joins Abhinandan Sekhri to discuss his autobiography _Stories I Must Tell...

William Gibson | The WeekHomeCulture & LifeFeaturesWilliam Gibson The persistent playwright who wrote The Miracle Worker Newsletter sign upNewsle...