A note on retrograde gene transfer efficiency and inflammatory response of lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with fug-e vs. Fug-b2 glycoproteins

A note on retrograde gene transfer efficiency and inflammatory response of lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with fug-e vs. Fug-b2 glycoproteins"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Pseudotyped lentiviral vectors give access to pathway-selective gene manipulation via retrograde transfer. Two types of such lentiviral vectors have been developed. One is the

so-called NeuRet vector pseudotyped with fusion glycoprotein type E, which preferentially transduces neurons. The other is the so-called HiRet vector pseudotyped with fusion glycoprotein

type B2, which permits gene transfer into both neurons and glial cells at the injection site. Although these vectors have been applied in many studies investigating neural network functions,

it remains unclear which vector is more appropriate for retrograde gene delivery in the brain. To compare the gene transfer efficiency and inflammatory response of the NeuRet vs. HiRet

vectors, each vector was injected into the striatum in macaque monkeys, common marmosets, and rats. It was revealed that retrograde gene delivery of the NeuRet vector was equal to or greater

than that of the HiRet vector. Furthermore, inflammation characterized by microglial and lymphocytic infiltration occurred when the HiRet vector, but not the NeuRet vector, was injected

into the primate brain. The present results indicate that the NeuRet vector is more suitable than the HiRet vector for retrograde gene transfer in the primate and rodent brains. SIMILAR

CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS DOUBLE VIRAL VECTOR TECHNOLOGY FOR SELECTIVE MANIPULATION OF NEURAL PATHWAYS WITH HIGHER LEVEL OF EFFICIENCY AND SAFETY Article Open access 11 January 2021

MAXIMIZING LENTIVIRAL VECTOR GENE TRANSFER IN THE CNS Article Open access 06 July 2020 TRANSDUCTION PATTERNS IN THE CNS FOLLOWING VARIOUS ROUTES OF AAV-5-MEDIATED GENE DELIVERY Article 15

August 2020 INTRODUCTION Gene transfer of functional molecules into neurons that give rise to a particular pathway is crucial for monitoring/manipulating neuronal activity within that

pathway. Emphasis was recently placed on the development of viral vectors that allow us to introduce foreign genes retrogradely into a given pathway and dissect it from others. For example,

recombinant glycoprotein-deleted rabies virus (RV) and canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2) vectors have been used not only for network-tracing studies1,2,3 but also for network-manipulation4,5,6 and

bioimaging studies7,8,9. However, these vectors are not suitable for chronic electrophysiological studies or gene therapeutic trials because of the cytotoxicity of their viral proteins. To

overcome this, it is necessary to create a novel non-cytotoxic vector that accommodates efficient retrograde gene transfer. Lentiviral vectors derived from human immunodeficiency virus type

1 (HIV-1) are a strong candidate since they exhibit low cytotoxicity because of their replication-defective form10,11. Given that these vectors are typically pseudotyped with vesicular

stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G), they are taken up preferentially from somas/dendrites of neurons. To enable retrograde gene transfer, pseudotyping of lentiviral vectors with rabies

virus glycoprotein (RV-G) was attempted12,13. Later, fusion envelope glycoproteins (FuG) consisting of distinct combinations of RV-G and VSV-G were developed to enhance the efficiency of

retrograde transgene delivery14,15,16,17,18,19. In particular, our research group previously reported the development of two types of lentiviral vectors with highly-efficient retrograde gene

transfer. One is known as HiRet vector, which is pseudotyped with the FuG-B2 type of fusion glycoprotein formed by the extracellular and transmembrane domains of RV-G and the membrane

proximal regions of VSV-G15,17. The other is known as NeuRet vector, which is pseudotyped with the FuG-E type of fusion glycoprotein consisting of the N-terminal segment of RV-G and the

membrane proximal region and the transmembrane/cytoplasmic domains of VSV-G19. Although these lentiviral vectors permit potent tools for pathway-selective gene manipulation in the central

nervous systems of rodents17,20,21,22,23 and primates24,25,26, it is still unclear which vector possesses a higher efficiency of retrograde transgene delivery. There has been considerable

interest in neurotoxic immune responses triggered by viral vectors transducing foreign proteins into antigen-presenting cells like astroglia. In fact, it has been demonstrated that

transduction of a foreign protein (i.e., green fluorescent protein) by adeno-associated virus serotype-9 (AAV9) causes inflammation associated with microglial and lymphocytic

infiltration27,28. Similar to AAV9, the HiRet vector displays gene transfer into both neurons and glial cells at the injection site15,17. Transgene delivery into glial cells by the HiRet

vector around the injection site might induce an adaptive immune response leading to prominent damage of transduced tissue. On the other hand, the NeuRet vector preferentially transduces

neuronal cells and rarely transduces dividing glial and neural stem/progenitor cells19,29. This neuronal specificity of the NeuRet vector reduces the risk of tumorigenesis due to prevention

of transgene insertion into the genome of dividing cells in the brain. However, the issue of how much of an immune response and/or neuroinflammation the HiRet and NeuRet vectors cause has

not as yet been addressed. The present study examined the suitability of the HiRet vs. NeuRet vectors for retrograde gene transfer in the brain by comparing them in terms of vector

production, transgene expression, and inflammatory response. The striatal input system was employed as a test system, and for comparison among different species, one rodent (rats) and two

nonhuman primate (macaques and marmosets) species were used. We have found that the NeuRet vector exhibits a higher retrograde gene transfer efficiency and a much weaker inflammatory

response than the HiRet vector. This combination of properties makes the NeuRet vector more viable approach to retrograde transgene delivery in the brains of primates and rodents. RESULTS

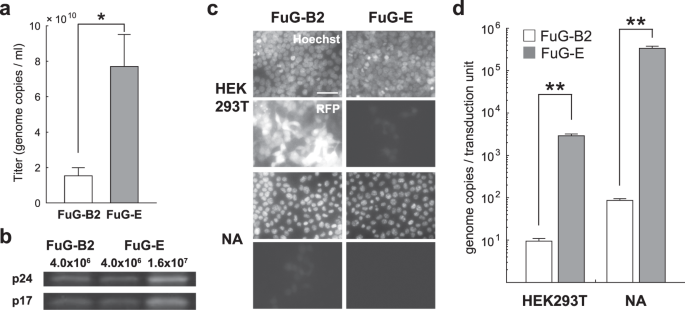

PRODUCTION EFFICIENCY OF THE FUG-B2 AND FUG-E PSEUDOTYPED LENTIVIRAL VECTORS We produced HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors carrying the red fluorescent protein (RFP) transgene by pseudotyping

with FuG-B2 or FuG-E glycoprotein as reported in previous studies17,19. To compare the recovery efficiency of the FuG-E and FuG-B2 pseudotype, the copy number of viral RNA in the vector

stock solutions with the same concentration volume was determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Fig. 1a). The RNA copy number in the vector stock solution of the FuG-E

pseudotype was significantly greater than that of the FuG-B2 pseudotype (Student’s _t_ test, _P_ < 0.05), and this RNA copy number of the FuG-E pseudotype was equivalent to that of the

VSV-G pseudotype (Supplementary Fig. S1). SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that the amount of viral protein (p24 and p17) content in the vector solutions adjusted to the same RNA titer (4.0 × 106

genome copies) did not differ between the FuG-E and FuG-B2 pseudotypes (Fig. 1b). This indicates that the vector stock solutions with identical RNA titer contained an equivalent number of

viral vector particles. We also found that the higher-titer vector solution (1.6 × 107 genome copies) of the FuG-E pseudotype contained more viral protein than the lower-titer vector

solution (Fig. 1b). These results demonstrate that the FuG-E pseudotype has a higher production efficiency than the FuG-B2 pseudotype. As reported in a previous study17, the FuG-B2

pseudotype transduced into HEK293T and Neuro2A cells, whereas the FuG-E pseudotype rarely transduced into these cells (Fig. 1c). The ratio of the RNA copy number to transducing units of the

FuG-E pseudotype was significantly higher than that of the FuG-B2 pseudotype in HEK293T and Neuro2A cell lines (Student’s _t_ test, _P_ < 0.01; Fig. 1d). These results led us to compare

the properties of the HiRet (FuG-B2) and NeuRet (FuG-E) vectors with the same genome titer, but not the functional titer. RETROGRADE GENE TRANSFER OF THE HIRET AND NEURET VECTORS IN MACAQUE

MONKEYS To compare the efficiency of retrograde gene delivery of the HiRet (FuG-B2) and NeuRet (FuG-E) vectors in the brain of macaque monkeys, striatal injections of each vector encoding

the RFP gene were made stereotaxically into both the caudate nucleus and the putamen (Fig. 2a). We first injected the HiRet vector (2.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml, 60 µl) and the NeuRet vector

with an equivalent titer (2.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml, 60 µl). Since the production efficacy of the NeuRet vector is higher than that of the HiRet vector, we then injected the NeuRet vector

with a higher titer (7.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml, 60 µl). To investigate the properties of gene transduction around the injection sites using both vectors with the same titer (2.5 × 1010

genome copies/ml), double immunofluorescence histochemistry was performed for RFP and either of the neuronal marker, neuronal nuclei (NeuN), or the astroglial marker, glial fibrillary acidic

protein (GFAP) (Fig. 2b). The ratio of RFP + NeuN-positive or RFP + GFAP-positive cells to the total RFP-positive cells was analyzed. In the NeuRet vector injection case, almost all

RFP-positive cells co-expressed NeuN (n = 2; 94.1% and 94.3%), while only a few RFP-positive cells co-expressed GFAP (n = 2; 3.2% and 3.5%), as we reported previously29. In the HiRet vector

injection case, on the other hand, a large number of RFP-positive cells also co-expressed GFAP (n = 2; 32.1% and 28.2%), as well as for NeuN (n = 2; 76.3% and 51.5%). Thus, the HiRet vector

exhibited gene transfer into both neurons and glial cells at the injection site, as reported in mice15,17, whereas the NeuRet vector showed marked neuronal specificity. To compare the

efficacy of retrograde gene delivery of the HiRet and NeuRet vectors with the same titer (2.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml), we analyzed the density of neuronal labeling in the substantia nigra

pars compacta (SNc), the centromedian-parafascicular thalamic complex (CM-Pf), and the supplementary motor area (SMA). In the SNc and CM-Pf, somewhat larger numbers of RFP-positive neurons

were found after the injection of the NeuRet than the HiRet vector (Fig. 3a). The average number of RFP-positive neurons transduced with the HiRet or NeuRet vector in the SNc was 456.2 or

520.6 cells per section (n = 2), respectively (Fig. 3b; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 1.1), while that of RFP-positive CM-Pf neurons in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case was 408.7 or 500.0,

respectively (Fig. 3c; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 1.2). Double immunofluorescence histochemistry for RFP and the dopaminergic neuron marker, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), confirmed that substantially

all RFP-positive neurons in the SNc were also immunostained for TH, and nearly half of the total TH-immunostained neurons expressed the RFP transgene in the NeuRet (46.3%; n = 2) and HiRet

(43.5%; n = 2) vector injection cases. On the other hand, the HiRet and NeuRet vectors with the same titer (2.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml) transduced only a small number of neurons in the SMA,

though neuronal labeling with the NeuRet vector was still noticeable in the ipsilateral hemisphere (Fig. 3a). However, a large number of labeled neurons were observed not only in the

ipsilateral but also in the contralateral SMA after the injection of the NeuRet vector with a higher titer (7.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml). The density of RFP-positive neurons in the case of

injecting the higher-titer NeuRet vector was greater than that in the case of the lower-titer NeuRet vector by approximately 1.9 or 4.0 times in the ipsilateral or contralateral SMA,

respectively (Fig. 3c). RETROGRADE GENE TRANSFER OF THE HIRET AND NEURET VECTORS IN MARMOSETS To compare retrograde gene transfer of the HiRet and NeuRet vectors in the brain of common

marmosets, we injected each vector with the same titer (1.0 × 1010 genome copies/ml, 10 µl) into the striatum (Fig. 4a). For analyzing the extent of glial transduction at the injection site

of each vector, double immunofluorescence histochemistry for RFP and GFAP was performed. Consistent with the results obtained in the macaque monkeys, many RFP-positive cells co-expressed

GFAP in the HiRet vector injection case, while few RFP-positive cells co-expressed GFAP in the NeuRet vector injection case. We analyzed the density of labeled neurons in the SNc, CM-Pf, and

Brodmann’s area 6 m (A6m). In the SNc, many RFP-positive neurons were observed after the NeuRet than the HiRet vector injection (Fig. 4b). The mean number of RFP-positive neurons in the

HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case was 86.0 or 120.0 cells per section (n = 2), respectively (Fig. 4c; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 1.4). Similar, but clearer, data about the superiority of the

NeuRet vector were obtained for neuronal labeling in the CM-Pf (Fig. 4b) and A6m (Fig. 4b). The mean number of RFP-positive CM-Pf neurons in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case was

215.5 or 501.1 cells per section (n = 2), respectively (Fig. 4c; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 2.3). The density of RFP-positive A6m neurons in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case was 34.6 or

70.1 for the ipsilateral hemisphere (n = 2), respectively (Fig. 4d; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 2.0), and it was 18.1 or 36.3 for the contralateral hemisphere (n = 2), respectively (Fig. 4d;

NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 2.0). RETROGRADE GENE TRANSFER OF THE HIRET AND NEURET VECTORS IN RATS To compare the extent of retrograde gene transfer of the HiRet and NeuRet vectors in the rat

brain, we injected each vector with the same titer (1.0 × 1010 genome copies/ml, 2 µl) into the striatum (Fig. 5a). We analyzed the number and density of neuronal labeling in the SNc, Pf,

and the primary motor cortex (M1). In the SNc, the equivalent number of RFP-positive neurons was observed after the injections of the HiRet and NeuRet vectors (Fig. 5b). The mean number of

RFP-positive neurons in the SNc was 95.0 ± 2.7 or 89.3 ± 4.8 cells per section (n = 4) in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case (Student’s _t_ test, _P_ = 0.341; Fig. 5c; NeuRet/HiRet

ratio = 0.9). On the other hand, the significant superiority of the NeuRet vector was obtained for neuronal labeling in the Pf and M1 (Fig. 5b). The average numbers of RFP-positive neurons

in the Pf were 246.1 ± 11.1 or 399.5 ± 24.3 cells per section (n = 4) in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case (Student’s _t_ test, _P_ < 0.01; Fig. 5c; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 1.6). The

density of RFP-positive M1 neurons in the HiRet or NeuRet vector injection case was 84.0 ± 3.7 or 198.7 ± 16.1 for the ipsilateral hemisphere (n = 4), respectively (Student’s _t_ test, _P_

< 0.01; Fig. 5d; NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 2.4), and it was 6.1 ± 0.6 or 68.2 ± 1.8 for the contralateral hemisphere (n = 4), respectively (Student’s _t_ test, _P_ < 0.001; Fig. 5d;

NeuRet/HiRet ratio = 11.2). NEUROINFLAMMATORY RESPONSES OF THE HIRET AND NEURET VECTORS As previously reported in mice17,19, we have shown that the HiRet vector transduces not only neurons

but also glial cells, while the NeuRet vector predominantly transduces neurons in primates. The HiRet vector may thus trigger an immune response due to the introduction of non-self proteins

into antigen-presenting cells around the injection site. In Nissl-stained sections from macaque monkeys injected with the HiRet vector, severe necrosis occurred around the injection site

(Fig. 6a). To clarify whether this tissue damage related to the immune response, immunofluorescence histochemistry for the microglial marker, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1

(Iba1), and the cytotoxic T cell marker, cluster of differentiation 8 (CD8) was performed. Many Iba1- and CD8-positive cells were observed around the injection site in the HiRet vector

injection case, indicating that microglial and lymphocytic infiltration appeared. In contrast to the HiRet vector, no marked necrosis around the injection site was observed after the

injections of lower or higher titer of the NeuRet vector. In the marmoset striatum, similar necrotic and microglial/lymphocytic infiltrative events were seen in the HiRet vector, but not the

NeuRet vector injection case (Supplementary Fig. S2). Following the intrastriatal injections of either vector, no tissue damage was detected in the rat brain (Fig. 6b). DISCUSSION In

previous studies15,16,17,19, it has been reported that pseudotyping a lentiviral vector with modified envelope glycoproteins, formed by RV-G and VSV-G, can improve the efficiency of gene

transfer through retrograde transport of the vector. This capability of the pseudotyped lentiviral vectors enables us to express a foreign gene in a particular circuit and remove/manipulate

the circuit, not only in rodents17,20,21,22,23 but also in nonhuman primates24,25,26. In our present work, we investigated the efficacy of transgene expression by the HiRet (FuG-B2) and

NeuRet (FuG-E) vectors through the intrastriatal injection of each vector in macaque monkeys, marmosets, and rats. First, we showed that the efficiency of retrograde gene delivery of the

NeuRet vector is greater than or equal to that of the HiRet vector, though this depended on the pathway or the species examined. It should be noted, however, that injections of the HiRet

vector and the low-titer NeuRet vector into the macaque striatum did not sufficiently label SMA neurons through the corticostriatal pathway. As also reported elsewhere29, the NeuRet vector

with a higher titer resulted in highly efficient retrograde gene transduction in the corticostriatal pathway, as well as in the nigrostriatal and thalamostriatal pathways. Second, our data

also showed that the NeuRet vector exhibits a smaller degree of tissue inflammation than the HiRet vector. Thus, the NeuRet vector could provide a powerful and safe tool to investigate the

functional roles of a given pathway in both primates and rodents. The pathway/species-dependent differences observed in gene transfer efficacy highlights a critical issue in

pathway-selective gene manipulation. We have shown that injections of the NeuRet vector achieve efficient retrograde gene transduction into nigrostriatal, thalamostriatal, and

corticostriatal neurons not only in macaque monkeys (see also Tanabe _et al_., 2017) but also in marmosets and rats. This indicates that regardless of the striatal input system, the NeuRet

vector successfully transduces foreign genes in multiple species. Of particular interest is that the pseudotyped lentiviral vectors only poorly induced retrograde gene transfer into

nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in mice15,16. It is therefore important to clarify the mechanisms underlying the pathway/species-dependence in retrograde gene transduction efficiency.

Concerning tissue inflammation, there was a significant difference between the NeuRet and HiRet vectors. The former preferentially transduces neuronal cells, whereas the latter induces gene

delivery into glial cells around the injection site. This is crucial because a neurotoxic immune response may be caused by transducing foreign proteins into antigen-presenting cells.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that the capability of AAV9 to transduce antigen-presenting cells in the central nervous systems of rodents and primates provokes the cell-mediated immune

response and neuroinflammation27,28. In the present study, we observed immune/neuroinflammatory responses around the injection site when the HiRet vector was injected into primate brains. On

the other hand, there was no such event in the case of the NeuRet vector injection. It is of interest that in the rat brain, necrosis was not seen around the injection site not only with

the NeuRet vector but also with the HiRet vector, as previously reported in mice17,23. These results emphasize the safety of the NeuRet vector, and inversely raise an alert over the use of

the HiRet vector especially in the primate brain. In addition to the pseudotyped lentiviral vectors, there are some other viral vectors that permit retrograde gene transfer in the central

nervous system. Recombinant glycoprotein-deleted RV and CAV-2 vectors have so far been utilized as tools for manipulating neuronal activity, for example in optogenetics4,5. However, the

potential cytotoxicity of these vectors may constrain long-term experiments or clinical applications. It is therefore necessary to develop a novel non-cytotoxic vector. In this regard, RV

vectors with low cytotoxicity, such as self-inactivated RV vector30 and double-deletion-mutant RV vector31, have recently been introduced. These RV vectors have been shown to express

transgene only transiently and insufficiently, so they rely on Cre- or Flp-mediated recombination and require other helper viral vectors or reporter conditional mouse lines. In addition, a

new variant of adeno-associated viral vector termed rAAV2-retro has been developed to induce transgene expression robustly in a retrograde fashion32. However, this vector has been reported

to have stronger tropisms for particular cell types in mice than the double-deletion-mutant RV vector31. Moreover, a major disadvantage of the AAV vector is the limited packaging size of

transgene (<5 kb)33, compared with the packaging size of lentiviral vectors (<7.5 kb)34. To identify the most appropriate vector for retrograde gene transfer, further investigations

are needed to compare the NeuRet vector with the above vectors from various perspectives, such as their efficiency, cytotoxicity, and the pathways involved. The HIV-1-based lentiviral vector

has been utilized for pathway-selective gene manipulation17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and gene therapeutic approaches to Parkinson’s disease in rodents and nonhuman primates35,36,37,38. Our

study demonstrates that the NeuRet vector achieves a higher efficiency of gene delivery than the HiRet vector in the primate and rodent brains. Moreover, the NeuRet vector induces

immune/inflammatory responses to a lesser extent than does the HiRet vector. This property of the NeuRet vector is ascribable to its high neuronal specificity, which minimizes adverse

side-effects such as neuronal loss adjacent to the injection site. In conclusion, the NeuRet vector pseudotyped with FuG-E might gain easy access to successful pathway-specific gene

manipulations or effective gene therapeutic trials against neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease through improved and safe retrograde delivery. METHODS ANIMALS Ten adult

nonhuman primates of either sex and eight adult male Wistar rats (250–350 g) were used for this study. Of the 10 nonhuman primates, six animals were macaque monkeys (four Japanese monkeys,

5.6–6.2 kg; two rhesus monkeys, 5.6–6.2 kg), and four animals were common marmosets (260–360 g). The experimental procedures were in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Welfare

and Animal Care Committee of the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University (Permission Number: 2015-033), and were conducted in line with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Nonhuman

Primates established by the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University (2010). Since the Guidelines require us to consider 3R-type recommendations in designing monkey experiments, we

decided to use two animals for each purpose. All experiments were performed in a special laboratory (biosafety level 2) designated for _in vivo_ animal infectious experiments that had been

placed at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University. Throughout the entire experiments, the animals were kept in individual cages that were placed inside a special safety cabinet. The

room temperature (23–26 °C for macaque monkeys and rats; 26–30 °C for marmosets) and the light condition (12-hr on/off cycle) were controlled. The animals were fed usually with dietary

pellets and had free access to water. Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering. VIRAL VECTOR PRODUCTION The construction of envelope plasmids (pCAGGS-FuG-B2 and pCAGGS-FuG-E) was

mentioned elsewhere17,19. The transfer plasmid (pCL20c-MSCV-cgfTagRFP) contained the cDNA encoding cysteine- and glycan-free (cgf) TagRFP39 under the control of the murine stem-cell virus

(MSCV) promoter. DNA transfection and viral vector preparation were carried out as previously described19,29. Briefly, HEK293T cells in 72 10-cm tissue culture dishes were transfected with

transfer, envelope, and packaging plasmids (pCAG-kGP4.1R and pCAG4-RTR2) by using the calcium-phosphate precipitation method. Eighteen hours after transfection, the medium was exchanged to a

fresh one, where the cells were incubated for 24 hr. The medium was then harvested and filtered through a 0.45-µm Millex-HV filter unit (Millipore, USA). Viral vector particles were

collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 16–18 hr and resuspended in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The particles were applied to a Sepharose Q FF ion-exchange column (GE

Healthcare, UK) in 0.01 M PBS and eluted with a linear <1.5 M NaCl gradient. The fractions were monitored at 260/280 nm of absorbance wavelength. The peak fractions containing the

particles were collected and condensed to 110 µl by centrifugation through a Vivaspin filter (Vivascience, UK). To measure RNA titer, viral RNA in 50 nl of the vector stock solution was

isolated by using a NucleoSpin RNA virus kit (Takara, Japan), and the copy number of the RNA genome was determined by quantitative PCR with Taq-Man technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

USA). The viral protein signals of the HiRet vector (4.0 × 106 genome copies) and the NeuRet vector (4.0 × 106 and 1.6 × 107 genome copies) were visualized by 4–12% SDS-acrylamide gel

electrophoresis and fluorescent staining (Oriole, BIO-RAD, USA). HEK293T and Neuro2A cells were transduced with the viral vectors (100 genome copies/cell), and stained with Hoechst 33342

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The transducing unit was estimated by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences, USA). The RNA copy number of each vector was divided by the transduction

unit to calculate the ratio of the RNA copy number to transducing units in each five individual experiment. SURGICAL PROCEDURES The macaque monkeys were initially sedated with ketamine

hydrochloride (5 mg/kg, i.m.) and xylazine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg, i.m.), and then anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (20 mg/kg, i.v.). During the surgery, the monkeys were kept

hydrated with a lactated Ringer’s solution (i.v.). An antibiotic (Ceftazidime; 25 mg/kg, i.v.) and an analgesic (Meloxicam; 0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) were applied at the initial anesthesia. After

removal of a portion of the skull, multiple injections of each vector were made unilaterally into the striatum by means of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided navigation system

(Brainsight Primate, Rogue Research, Canada). In total, 60 µl of the FuG-B2 (2.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml) or FuG-E (2.5 × 1010 or 7.5 × 1010 genome copies/ml) pseudotyped lentiviral vector

was injected through a 10-µl Hamilton microsyringe into both the caudate nucleus and the putamen at six rostrocaudal levels (3–5 µl/site, two sites per track, eight tracks per monkey; three

tracks for the caudate nucleus and five tracks for the putamen). After the injections, the scalp incision was sutured. The monkeys were monitored until the full recovery from the anesthesia.

The marmosets were initially sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (50 mg/kg, i.m.) and xylazine hydrochloride (2 mg/kg, i.m.), and then anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (15 mg/kg,

i.p.). An antibiotic (Cefmetazole; 25 mg/kg, i.m.) and 10 ml of acetated Ringer’s solution (s.c.) were administrated before and after the operation. After the craniotomy, multiple injections

of each vector were made unilaterally into the striatum of which coordinates were measured by using MRI. In total, 10 µl of the FuG-B2 or FuG-E pseudotyped lentiviral vector (each 1.0 ×

1010 genome copies/ml) was injected through a 10-µl Hamilton microsyringe into both the caudate nucleus and the putamen at three rostrocaudal levels (1 µl/site, two sites per track, five

tracks per marmoset; three tracks for the caudate nucleus and two tracks for the putamen). After the injections, the scalp incision was sutured, and an analgesic (Meloxicam; 1 mg/kg, s.c.)

was applied. The rats were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine hydrochloride (50 mg/kg, i.m.) and xylazine hydrochloride (4 mg/kg, i.m.). In total, 2 µl of the FuG-B2 or FuG-E

pseudotyped lentiviral vector (each 1.0 × 1010 genome copies/ml) was stereotaxically injected into the right dorsal striatum (0.5 µl/site, four sites) through a glass microinjection

capillary connected to a microinfusion pump. The anteroposterior, mediolateral, and dorsoventral coordinates (mm) from the bregma and dura were 1.5/2.8/5.8, 1.5/2.8/4.0, 0.0/3.5/5.5 and

0.0/3.5/4.0 for the dorsal striatum according to an atlas of the rat brain40. IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY After a survival period of four weeks, the animals were deeply anesthetized with an

overdose of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.v., for macaque monkeys; 50 mg/kg, i.p., for marmosets; 100 mg/kg, i.p., for rats) and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M PBS, followed by 10%

formalin in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The removed brains were postfixed in the same fresh fixative overnight at 4 °C, and saturated with 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS at 4 °C. A freezing microtome

was used to cut coronal sections serially at the 50-µm thickness for macaque monkeys and the 40-µm thickness for marmosets and rats. Every tenth section was mounted onto gelatin-coated glass

slides and Nissl-stained with 1% Cresyl violet. Immunoperoxidase staining for tRFP was performed as described previously29. The sections were pretreated with 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min, rinsed

three times in 0.1 M PBS, and immersed in 1% skim milk for 1 hr. Then, the sections were incubated for 2 days at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal anti-tRFP antibody (1:2,500 dilution; Thermo

Fisher Scientific) in 0.1 M PBS containing 2% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. The sections were subsequently incubated with biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1,000

dilution; Jackson laboratories, USA) in the same fresh medium for 2 hr at room temperature, followed by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex kit (ABC Elite; 1:200 dilution; Vector

laboratories, USA) in 0.1 M PBS for 2 hr at room temperature. The sections were reacted for 10–20 min in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.04% diaminobenzine tetrahydrochloride

(Wako, Japan), 0.04% NiCl2, and 0.002% H2O2. The reaction time was set to make the density of background immunostaining almost identical. These sections were counterstained with 0.5% Neutral

red, mounted onto gelatin-coated glass slides, dehydrated, and coverslipped. For double immunofluorescence histochemistry for RFP and one of NeuN, GFAP, and TH, the sections were immersed

in 1% skim milk for 1 hr and incubated for 2 days at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal anti-tRFP antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and mouse monoclonal antibodies; anti-NeuN

antibody (1:2000 dilution; Millipore, USA), anti-GFAP antibody (1:500 dilution; Sigma, USA), and anti-TH antibody (1:500 dilution; Millipore). The sections were subsequently incubated for 2

hr at room temperature with a cocktail of Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:400 dilution; Jackson laboratories) and Alexa 647-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:400

dilution; Jackson laboratories) in the same fresh medium. For double immunofluorescence histochemistry for Iba1 and CD8, rabbit monoclonal anti-Iba1 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Wako), mouse

monoclonal anti-CD8 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Bio-Rad, USA), Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson laboratories), and Alexa 647-conjugated donkey

anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson laboratories) were used following the staining protocol described above. IMAGE ACQUISITION AND HISTOLOGICAL ANALYSES To capture brightfield

microscopic images, an optical microscope equipped with a high-grade charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Biorevo, Keyence, Japan) and a scientific CMOS camera (In Cell Analyzer 2200, GE

Healthcare) were used. A confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM800, Carl Zeiss, USA) were used to take fluorescent microscopic images. The number or density of RFP-positive cells in each

brain region were calculated with Neurolucida software (MicroBrightField, USA) and Matlab software (Mathworks, USA), as previously described29. For counts of RFP-positive cells in the SNc,

11, 7, or 6 sections were used in macaque monkeys (500-μm apart), marmosets (400-μm apart) or rats (320-μm apart), respectively. For counts of RFP-positive cells in the CM-Pf or Pf thalamic

nucleus, 7, 4, or 4 sections were used in macaque monkeys, marmosets or rats, respectively. For measurements of the density of RFP-positive cells in the cortical areas, 10, 8, or 4 sections

were used for the macaque SMA in macaque monkeys, area A6m in marmosets, or M1 in rats, respectively. Stereological cell counting assisted with StereoInvestigator software (MBF Biosciences,

USA) was performed to estimate the ratio of RFP + NeuN-positive or RFP + GFAP-positive cells to the total RFP-positive cells at the injection sites and the ratio of RFP-positive cells to the

total TH-positive cells in the SNc. Labeled cells in 100-μm × 100-μm counting frames equally spaced across a 500-μm × 500-μm grid were counted with an 18-μm-high optical dissector.

STATISTICS Values were expressed as the mean ± SEM of the data. For statistical comparisons, Student’s _t_ tests were used with significance set at *_P_ < 0.05, **_P_ < 0.01, or ***_P_

< 0.001. REFERENCES * Dölen, G., Darvishzadeh, A., Huang, K. W. & Malenka, R. C. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. _Nature_

501, 179–184 (2013). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schwarz, L. A. _et al_. Viral-genetic tracing of the input-output organization of a central noradrenaline

circuit. _Nature_ 524, 88–92 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wallace, M. L. _et al_. Genetically distinct parallel pathways in the entopeduncular nucleus

for limbic and sensorimotor output of the basal ganglia. _Neuron_ 94, 138–152 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Namburi, P. _et al_. A circuit mechanism for

differentiating positive and negative associations. _Nature_ 520, 675–678 (2015). ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rajasethupathy, P. _et al_. Projections from neocortex

mediate top-down control of memory retrieval. _Nature_ 526, 653–659 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Carter, M. E., Soden, M. E., Zweifel, L. S. &

Palmiter, R. D. Genetic identification of a neural circuit that suppresses appetite. _Nature_ 503, 111–114 (2013). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Osakada, F.

_et al_. New rabies virus variants for monitoring and manipulating activity and gene expression in defined neural circuits. _Neuron_ 71, 617–631 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Gong, Y. _et al_. High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. _Science_ 350, 1361–1366 (2015). Article ADS CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kim, J. _et al_. Changes in the excitability of neocortical neurons in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are not specific to

corticospinal neurons and are modulated by advancing disease. _J. Neurosci._ 37, 9037–9053 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Naldini, L. _et al_. _In Vivo_ Gene

Delivery and Stable Transduction of Nondividing Cells by a Lentiviral Vector. _Science._ 272, 263–267 (1996). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Naldini, L., Blömer, U., Gage, F.

H., Trono, D. & Verma, I. M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. _Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci._ 93, 11382–11388 (1996). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mazarakis, N. D. _et al_. Rabies virus glycoprotein pseudotyping of lentiviral vectors

enables retrograde axonal transport and access to the nervous system after peripheral delivery. _Hum. Mol. Genet._ 10, 2109–2121 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kato, S. _et

al_. Efficient gene transfer via retrograde transport in rodent and primate brains using a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vector pseudotyped with rabies virus glycoprotein. _Hum.

Gene Ther._ 18, 1141–1151 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Carpentier, D. _et al_. Enhanced pseudotyping efficiency of HIV-1 lentiviral vectors by a Rabies/Vesicular

Stomatitis Virus chimeric envelope glycoprotein. _Gene Ther._ 19, 761–774 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kato, S. _et al_. A lentiviral strategy for highly efficient

retrograde gene transfer by pseudotyping with fusion envelope glycoprotein. _Hum. Gene Ther._ 22, 197–206 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kato, S. _et al_. Neuron-specific

gene transfer through retrograde transport of lentiviral vector pseudotyped with a novel type of fusion envelope glycoprotein. _Hum. Gene Ther._ 22, 1511–152 (2011). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Kato, S. _et al_. Selective neural pathway targeting reveals key roles of thalamostriatal projection in the control of visual discrimination. _J. Neurosci._ 31, 17169–17179

(2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schoderboeck, L. _et al_. Chimeric rabies SADB19-VSVg-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors mediate long-range retrograde

transduction from the mouse spinal cord. _Gene Ther._ 22, 357–364 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kato, S., Kobayashi, K. & Kobayashi, K. Improved transduction efficiency

of a lentiviral vector for neuron-specific retrograde gene transfer by optimizing the junction of fusion envelope glycoprotein. _J. Neurosci. Methods_ 227, 151–158 (2014). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Sooksawate, T. _et al_. Viral vector-mediated selective and reversible blockade of the pathway for visual orienting in mice. _Front. Neural Circuits_ 7, 162 (2013).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ishida, A. _et al_. Causal link between the cortico-rubral pathway and functional recovery through forced impaired limb use in rats with

stroke. _J. Neurosci._ 36, 455–467 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Matsuda, T. _et al_. Distinct neural mechanisms for the control of thirst and salt appetite in

the subfornical organ. _Nat. Neurosci._ 20, 230–241 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kato, S. _et al_. Action selection and flexible switching controlled by the intralaminar

thalamic neurons. _Cell Rep._ 22, 2370–2382 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Inoue, K. _et al_. Immunotoxin-mediated tract targeting in the primate brain: selective

elimination of the cortico-subthalamic “hyperdirect” pathway. _PLoS ONE_ 7, e39149, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039149 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Kinoshita, M. _et al_. Genetic dissection of the circuit for hand dexterity in primates. _Nature_ 487, 235–238 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tohyama, T. _et

al_. Contribution of propriospinal neurons to recovery of hand dexterity after corticospinal tract lesions in monkeys. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 114, 604–609 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ciesielska, A. _et al_. Cerebral infusion of AAV9 vector-encoding non-self proteins can elicit cell-mediated immune responses. _Mol. Ther._ 21, 158–166

(2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Samaranch, L. _et al_. AAV9-Mediated expression of a non-self protein in nonhuman primate central nervous system triggers widespread

neuroinflammation driven by antigen-presenting cell transduction. _Mol. Ther._ 22, 329–337 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tanabe, S. _et al_. The use of an

optimized chimeric envelope glycoprotein enhances the efficiency of retrograde gene transfer of a pseudotyped lentiviral vector in the primate brain. _Neurosci. Res._ 120, 45–52 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Cibatti, E., González-Rueda, A., Mariotti, L., Morgese, F. & Tripodi, M. Life-long genetic and functional access to neural circuit using

self-inactivating rabies virus. _Cell_ 170, 1–11 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Chatterjee, S. _et al_. Nontoxic, double-deletion-mutant rabies viral vectors for retrograde targeting of

projection neurons. _Nat. Neurosci._ 21, 638–646 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tervo, D. G. R. _et al_. A designer AAV variant permits efficient retrograde

access to projection neurons. _Neuron_ 92, 372–382 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thomas, C. E., Ehrhardt, A. & Kay, M. A. Progress and problems with the

use of viral vectors for gene therapy. _Nat. Rev. Genet._ 4, 346–358 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * al Yacoub, N., Romanowska, M., Hartinova, N. & Foerster, J.

Optimized production and cocentration of lentiviral vectors containing large inserts. _J. Gene Med._ 9, 579–584 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Björklund, A. _et al_. Towards

a neuroprotective gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease: use of adenovirus, AAV and lentivirus vectors for gene transfer of GDNF to the nigrostriatal system in the rat Parkinson model.

_Brain Res._ 886, 82–98 (2000). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kordower, J. H. _et al_. Neurodegeneration prevented by lentiviral vector delivery of GDNF in primate models of Parkinson’s

disease. _Science_ 290, 767–773 (2000). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Palfi, S. _et al_. Lentivirally delivered glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor increases the

number of striatal dopaminergic neurons in primate models of nigrostriatal degeneration. _J. Neurosci._ 22, 4942–4954 (2002). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ridet,

J. L., Bensadoun, J. C., Déglon, N., Aebischer, P. & Zurn, A. D. Lentivirus-mediated expression of glutathione peroxidase: neuroprotection in murine models of Parkinson’s disease.

_Neurobiol. Dis._ 21, 29–34 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Suzuki, T. _et al_. Development of cysteine-free fluorescent proteins for the oxidative environment. _PLoS ONE_ 7

(2012). * Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. _The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates_. _7th ed_. (Academic Press, New York, 2013). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to M.

Sugawara for purification of the vectors, K. Kimura, K. Nagaya, and N. Nagaya for technical assistance, and Dr. A. MacIntosh for language editing of the manuscript. This work was supported

at least in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (26112002 to K.K., 15H05879 and 17H 05565 to K.I. and 16H02454 to M.T.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science,

and Technology of Japan and by Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS: JP17dm0207052 to K.K. and JP17dm0207003 to M.T.) from Japan Agency for Medical

Research and Development (AMED). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Systems Neuroscience Section, Department of Neuroscience, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University,

Inuyama, Aichi, 484-8506, Japan Soshi Tanabe, Shiori Uezono, Hitomi Tsuge, Maki Fujiwara, Ken-ichi Inoue & Masahiko Takada * Cognitive Neuroscience Section, Department of Neuroscience,

Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Inuyama, Aichi, 484-8506, Japan Miki Miwa & Katsuki Nakamura * Department of Molecular Genetics, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Fukushima

Medical University School of Medicine, Fukushima, Fukushima, 960-1295, Japan Shigeki Kato & Kazuto Kobayashi * PRESTO, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Kawaguchi, Saitama, 332-0012,

Japan Ken-ichi Inoue Authors * Soshi Tanabe View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shiori Uezono View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hitomi Tsuge View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maki Fujiwara View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Miki Miwa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shigeki Kato View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Katsuki Nakamura View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kazuto Kobayashi View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ken-ichi Inoue View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Masahiko Takada View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.T., K.K., K.I. and M.T. designed the experiments. S.K. and K.K. prepared

the viral vectors. M.F. and K.I. performed the _in vitro_ experiments. S.T., S.U., H.T., M.M., K.N. and K.I. performed the _in vivo_ experiments. S.T. and K.I. analyzed the data. S.T., K.I.

and M.T. wrote the manuscript, and all authors discussed the data and commented on the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Ken-ichi Inoue or Masahiko Takada. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use

is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Tanabe, S., Uezono, S., Tsuge, H. _et al._ A note on retrograde gene transfer

efficiency and inflammatory response of lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with FuG-E vs. FuG-B2 glycoproteins. _Sci Rep_ 9, 3567 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39535-1 Download

citation * Received: 30 May 2018 * Accepted: 04 January 2019 * Published: 05 March 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39535-1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following

link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature

SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

Police shut down 'vessel' claims after death of two children on popular beachPolice in Dorset have ruled out contact between a vessel and swimmers who were injured at Bournemouth Beach on Wednesday...

Undiksha institutional repository system undiksha repositoryCahyani, Ida Ayu Dita Safitri (2025) _TINJAUAN HUKUM HAK ASASI MANUSIA TERHADAP DISKRIMINASI LESBIAN GAY BISEKSUAL DAN T...

Fourteen leicester city january transfer rumours and what happened nextThe transfer rumour mill hasn’t produced quite so many Leicester City links as is typical for a January window, but perh...

Kelsey asbille chow age: how old is yellowstone star kelsey chow?Kelsey Asbille Chow is an American actress who is proud of her Chinese roots, and she has previously starred in Pair of ...

Sodium butyrate enhances stat 1 expression in plc/prf/5 hepatoma cells and augments their responsiveness to interferon-αSUMMARY Although interferon-α (IFN-α) has shown great promise in the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis, the anti-tumo...

Latests News

A note on retrograde gene transfer efficiency and inflammatory response of lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with fug-e vs. Fug-b2 glycoproteinsABSTRACT Pseudotyped lentiviral vectors give access to pathway-selective gene manipulation via retrograde transfer. Two ...

Daniel levy sets stance on sacking tottenham boss jose mourinhoTottenham chairman Daniel Levy is highly unlikely to axe Jose Mourinho midway through the season with Spurs still compet...

Why the promised fourth industrial revolution hasn’t happened yetIt’s nearly a decade since the term “fourth industrial revolution” was coined, yet many people won’t have heard of it, o...

Massachusetts governor may challenge gay marriageBOSTON — Gov. Mitt Romney said Friday that he might turn to the courts in his fight to keep Massachusetts from issuing s...

Page Not Found很抱歉,你所访问的页面已不存在了。 如有疑问,请电邮[email protected] 你仍然可选择浏览首页或以下栏目内容 : 新闻 生活 娱乐 财经 体育 视频 播客 新报业媒体有限公司版权所有(公司登记号:202120748H)...