Accurate and efficient band gap predictions of metal halide perovskites using the dft-1/2 method: gw accuracy with dft expense

Accurate and efficient band gap predictions of metal halide perovskites using the dft-1/2 method: gw accuracy with dft expense"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The outstanding optoelectronics and photovoltaic properties of metal halide perovskites, including high carrier motilities, low carrier recombination rates, and the tunable spectral

absorption range are attributed to the unique electronic properties of these materials. While DFT provides reliable structures and stabilities of perovskites, it performs poorly in

electronic structure prediction. The relativistic GW approximation has been demonstrated to be able to capture electronic structure accurately, but at an extremely high computational cost.

Here we report efficient and accurate band gap calculations of halide metal perovskites by using the approximate quasiparticle DFT-1/2 method. Using AMX3 (A = CH3NH3, CH2NHCH2, Cs; M = Pb,

Sn, X = I, Br, Cl) as demonstration, the influence of the crystal structure (cubic, tetragonal or orthorhombic), variation of ions (different A, M and X) and relativistic effects on the

electronic structure are systematically studied and compared with experimental results. Our results show that the DFT-1/2 method yields accurate band gaps with the precision of the GW method

with no more computational cost than standard DFT. This opens the possibility of accurate electronic structure prediction of sophisticated halide perovskite structures and new materials

design for lead-free materials. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ACCURATE AND EFFICIENT BAND-GAP PREDICTIONS FOR METAL HALIDE PEROVSKITES AT FINITE TEMPERATURE Article Open access 15

November 2022 THE LANDÉ FACTORS OF ELECTRONS AND HOLES IN LEAD HALIDE PEROVSKITES: UNIVERSAL DEPENDENCE ON THE BAND GAP Article Open access 02 June 2022 ANALYZING THE STRUCTURAL,

OPTOELECTRONIC, AND THERMOELECTRIC PROPERTIES OF INGEX3 (X = BR) PEROVSKITES VIA DFT COMPUTATIONS Article Open access 09 October 2024 INTRODUCTION Hybrid organic-inorganic lead halide

perovskites have become the jewel in the crown in the field of photovoltaics since the pioneering work by Kojima _et al_. and Im _et al_.1,2. In just four years the power conversion

efficiency of solar cells based on hybrid perovskites has rapidly increased from an initial promising value of 9%3 to over 22%4. In addition to the outstanding performance, simple and

cost-effective fabrication, i.e. solution-processing techniques, render them one of the most desirable and most studied semiconductor materials in the field of photovoltaics5. Their

extraordinary properties, including high carrier mobilities, low carrier recombination rates, and the tunable spectral absorption range are attributed to the unique electronic properties of

these materials5,6,7. Thanks to the enormous interest from the scientific community, the field of hybrid perovskites has quickly expanded in terms of types of materials by substituting one

or more of the organic or inorganic ions in one of the most studied perovskites, methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3), to obtain the metal halide perovskites AMX3: (A = Cs, CH3NH3,

CH2NHCH2, M = Sn, Pb; X = I, Br, Cl). Despite the rapid progress made in the last few years in terms of the conversion efficiency, the understanding of the fundamental electronic properties

of AMX3 perovskites is rather limited. This is especially true for realistic structures in working devices, which often are compounds with mixtures of more than one organic cation, metal

cation or halide anion with sophisticated surfaces and interfaces1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The challenges to fundamental understanding of the electronic structure of AMX3 perovskites stem from their

rich chemical and physical properties and the interplay of these properties6,7. In this context, a first-principles computational approach capable of reliably calculating the materials

properties (electronic and thermodynamic) is essential. While standard DFT provides reliable structures and stabilities of perovskites, it severely underestimates the band gaps8,9,10. The

relativistic GW approximation has been demonstrated to be able to capture their electronic structure accurately but at an extremely high computational cost. Several research

groups8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 have successfully applied the GW method to predicting electronic structures of AMX3 perovskites. Even _et al_.8 have identified the importance of a giant

spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effect (about 1.0 eV) in the lead iodide perovskites, acting mainly on the conduction band (mainly consisting of Pb states). Taking SOC into account in a

relativistic GW approach, Brivio _et al_.9 predicted an unconventional band dispersion relation and a Dresselhaus splitting at the band edges in pseudo-cubic CH3NH3PbI3, which indicates a

direct-indirect band gap character. This theoretical prediction was recently confirmed6,7 by two groups of researchers independently, revealing the mechanism behind the slow charge

recombination in these materials. Umari _et al_.10 studied the substitution of Pb by Sn and found the SOC effect on Sn perovskites to be much smaller (about 0.4 eV). The same group of

researchers also looked at the substitution of halide ions in CH3NH3PbX3 11 and nicely reproduced experimental findings in optical behavior, such as an increase of the band gap when moving

from I to Cl. A few other theoretical studies at GW level include the investigation of polar phonons12, crystal structure effects and phase transitions13,14, exciton binding energies15, and

band gap trends16 in AMX3. The above mentioned GW studies have been very important in understanding the chemistry and physics of these materials and providing materials design inspirations.

However, the GW calculations of realistic structures of metal halide perovskites remain challenging because of i) spin-orbit coupling effects ii) the complex structures and phase transitions

in these materials iii) the necessary compromise between the size of the system studied and the extremely high computational cost. This leads to the quest for an accurate and cost effective

theoretical framework for electronic structure calculations of realistic AMX3 structures and possibly the A/M/X mixed compounds. Here, we apply a recently developed approximate

quasiparticle method, namely the DFT-1/2 method17,18, which allows us to accurately model the band gaps of AMX3 perovskites with minimal computational cost. The DFT-1/2 calculated electronic

properties of AMX3 perovskites are compared with those calculated with the GW method and with experimental data. Trends in the interplay of geometrical properties and electronic structure

properties are analyzed systematically. Our results indicate that the DFT-1/2 method yields band gaps with a GW precision, but with a computational cost similar to standard DFT, opening the

way to the study of sophisticated structures and new materials design. COMPUTATIONAL METHODS AND STRUCTURAL MODELS The initial structure optimizations are performed using DFT within the

local density approximation (LDA)19 as implemented in the Vienna _ab-initio_ simulation package (VASP)20. The exchange-correlation (XC) functional is used as parameterized by Perdew and

Zunger21. The outermost _s_, _p_, and _d_ (in the case of Pb and Sn) electrons are treated as valence electrons whose interactions with the remaining ions is modeled by pseudopotentials

generated within the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method22. It is well recognized that the orthorhombic↔tetragonal↔cubic (size-dependent, temperature-dependent, composition-dependent)

phase transitions in AMX3 perovskites can significantly alter their optical as well as electrical properties and thus impact their applications. Therefore, we also considered all three

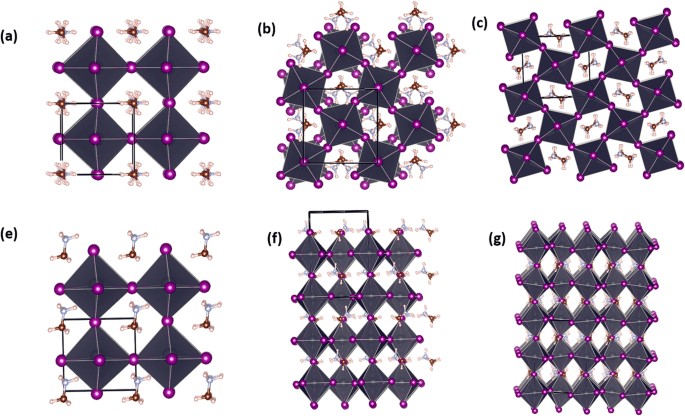

structures. Figure 1 shows the crystal structures and unit cells used in the DFT calculations. Taking CH3NH3PbI3 as an example, unit cells with 12, 48, and (also) 48 atoms are used for the

case of cubic, tetragonal, and orthorhombic crystal structures, respectively. During the optimization, the positions of the atoms, and the shape and volume of the unit cell are all allowed

to relax. Using cubic CH3NH3PbI3 unit cell as an example, an energy cutoff of 400 eV and 6 × 6 × 6 _k_-point are sufficient for fairly good convergence in total energy and lattice

parameters. For the sake of high accuracy, a energy cutoff of 500 eV and 10 × 10 × 10, 8 × 8 × 6, and 6 × 8 × 6 _k_-point meshes (for cubic, tetragonal and orthorhombic structures,

respectively) are used to achieve energy and force convergence of 0.1 meV and 2 meV/Å, respectively. DFT-LDA slightly underestimates the lattice parameters of the AMX3 structures by about 1%

to 3.5% depending on the composition of the compound and its structure. Usually, such an underestimation of lattice parameters leads to a small overestimation of the band gaps, e.g., by

about 70–150 meV for group III/V semiconductors23, taking volume deformation potentials into account. However, the opposite is found for metal halide perovskites, namely, an underestimation

of the band gaps. The deviations of the band gaps (compared to those with experimental lattice constants) are in the range of 100 meV to 250 meV when using LDA-optimized lattice constants.

The inclusion of Van der Waal corrections (DFT-D3 and DFT-TS) resulted in significant improvement of the DFT calculated lattice parameters. However, for each scheme, the degree of

improvement are different for different materials. For example, DFT-D3 scheme produce the best results for all inorganic AMX3, such as CsSnI3 and CsPbI3 (slight overestimation of about

0.3%), while DFT-TS performs best results for hybrid AMX3, such as, CH3NH3PbI3 (slight underestimation of about 0.1%). Due to a wide range of materials (both hybrid and all inorganic metal

halide) included in this work, to be consistent, all the electronic structure calculations were performed with corrected lattice parameters by expanding the lattice parameters proportionally

(to match experimental volume of the cells) while keeping the LDA-optimized shape of the cells. This procedure keeps the _ab-initio_ aspects of our approach without compromising accuracy.

As an example, a band gap difference of 0.04 eV was found for CH3NH3PbI3 when using this procedure (DFT-1/2 band gaps of 1.84 eV _vs_ 1.88 eV). The subsequent electronic structure

calculations were performed using the DFT-1/2 method. The DFT-1/2 method stems from Slater’s proposal of an approximation for the excitation energy, a transition state method24,25, to reduce

the band gap inaccuracy by introducing a half-electron/half-hole occupation. Ferreira _et al_.17 extended the method to modern DFT and particularly to solid-state systems, by assuming that

the excited electron in the conduction band of a semiconductor usually occupies Bloch-like states with nearly vanishing self-energy, while the hole left in the valence band is localized with

a finite self-energy. The self-energy of the hole was corrected by modifying the corresponding pseudopotentials of the atoms (in real space) by removing half an electron from the orbitals

that contribute to the top of the valence band17,18. The DFT-1/2 method has been demonstrated to be a successful approximate quasiparticle method for a large range of materials, including

group III/V semiconductors, intermediate and large band gap nitrides, oxides, and other materials17,18. Fortunately, the computational effort is the same as for standard DFT, with a

straightforward inclusion of SOC when coupled with VASP20. In this paper, we have applied the DFT-1/2 method (the LDA-1/2 version of ref.17) by using an occupation number of eight and proper

cutoff radii (CUT) for the M cations and X anions in the AMX3 compounds (Table 1). When determining these parameters, we have followed three rules: (i) the parameter CUT is chosen so as to

maximize the band gap, ii) this parameter is transferable to different chemical environments in the family of metal halide perovskites, iii) the corrections of the A cations were not

included mainly because A cations were demonstrated to not influence the band gap and band edges of metal halide perovskites. A schematic illustration of the application procedure of the

DFT-1/2 method included in Fig. 1S in the Supplementary Material. Also shown in Table 1, the location of the valence band maximum are mostly located in the real space around the anions (Cl,

Br and I) in a certain radius. The values of the CUT radius show an interesting trend: the larger the halogens ions are, the larger the CUT. To validate the application of the DFT-1/2

method, a direct comparison of the band gaps obtained using the DFT-1/2 method with GW band gaps calculated by Brivio _et al_.9 (CH3NH3PbI3, CH2NHCH2SnI3) and Mosconi _et al_.12 (AMX3: A =

CH3NH3/CH2NHCH2, M = Pb/Sn, X = I, Br, Cl) are shown in Table 1S of the Supplementary Material. The agreement between the DFT-1/2 and GW band gaps is excellent, with a maximum difference of

less than 0.2 eV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION COMPARISON OF DFT AND DFT-1/2 APPLIED TO PSEUDO-CUBIC CH3NH3PBI3 To compare the performance of DFT-1/2 with standard DFT in electronic structure

calculations, we choose as an example the most studied metal halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 with a pseudo-cubic structure. It is shown in Fig. 2(a) that DFT (LDA) indeed underestimates the

band gap severely, which is found to be 1.47 eV and 0.39 eV without and with SOC, respectively. The tendency of DFT to underestimate band gaps is traditionally associated with the energy

cost to excite electron-hole pair. Thanks to the self-energy correction, DFT-1/2 (LDA-1/2) performs extremely well with band gaps of 2.77 eV and 1.68 eV without and with SOC, respectively;

see Fig. 2(b). The latter value is only 0.01 eV larger than the value of 1.67 eV calculated by Brivio _et al_.9 using the GW approach. Both values are slightly higher than the experimental

value of about 1.60 eV27,28. As compared to DFT, both the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) calculated with DFT-1/2 shifts downwards and upwards in energy, resulting in a band gap

widening of about 1.30 eV both with and without SOC. (see Supplementary Material) In addition, the inclusion of SOC also leads to an indirect gap of 1.64 eV between the highest VB state and

lowest CB state, which is 0.04 eV lower than the direct band gap. In comparison to other theoretical predictions of 20 meV of this difference using the HSE06 hybrid fuctional29, and 75 meV7

using self-consistent GW, our value is the close to the very recent experimental finding of an activation energy of 47 meV6. It should be noted that the direct-indirect character of the band

gap in CH3NH3PbI3 is also found by us in CH3NH3PbBr3 and CH3NH3PbCl3 for a pseudo-cubic structure, with energy differences of about 0.03 eV (not shown). DFT-1/2 RESULTS FOR AMX3 (A =

CH3NH3, CH2NHCH2, CS, M = PB, SN, X = I, BR, CL) We applied the DFT-1/2 methodto calculate the electronic structure of nine AMX3 perovskites with their preferred crystal structures at room

temperature30,31,32,33,34,35,36: i) (pseudo-) cubic for CH3NH3PbBr3 30, CH3NH3PbCl3 30, and CH3NH3SnCl3 36 ii) tetragonal for CH3NH3PbI3 30, CH2NHCH2PbI3 31, and CH3NH3SnI3 35 iii)

orthorhombic for CsPbI3 32, CH2NHCH2SnI3 33, and CsSnI3 34. Table 2 and Fig. 3 summarize DFT-optimized lattice parameters and DFT-1/2 calculated band gaps and their comparison with

experimental data and GW results from literature37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. Despite the approximation made in the procedure of adapting to the experimental lattice parameters (see Section

computational methods) and the use of relatively small unit cells of the structures, the DFT-1/2 band gaps are in good agreement with experimental and GW results. The maximum discrepancy is

about 0.2 eV, with the majority of the band gaps slightly overestimated and a few slightly underestimated. Special attention needs to be paid to the case of CsPbI3 due to the fact that the

room-temperature crystal structure is uncertain, which is an indication of a metastable phase at the experimental conditions. Therefore, one has to be careful when comparing a band gap value

obtained from theoretical calculations for a certain structure that is different in experiments. The relatively large overestimation of the band gap of CsPbI3 can be understood by assuming

in the experiment an intermediate configuration between a cubic and orthorhombic assembling structure. Indeed, the average band gap of cubic (α-) CsPbI3 and orthorhombic (γ-) CsPbI3 is 1.72

eV, which is only 0.02 eV lower than the experimental value of 1.74 eV. A few general trends are observed from Fig. 3 and Table 2: * i) For the same composition, the band gap decreases with

increasing ordering in the crystal, namely orthorhombic >tetragonal >cubic. The magnitude of the differences is generally small for systems with CH3NH3, intermediate for CH2NHCH2, and

large for Cs cations. Two extreme cases are CH3NH3PbI3 with a difference of 0.03 eV (cubic _vs_ tetragonal) and CsSnI3 with a difference of 0.52 eV (cubic _vs_ orthorhombic). The small band

gap value of CsSnI3 in a cubic structure was also predicted using the GW method13,15 (DFT-1/2: 0.82 eV, GW: 0.60 eV and 1.01 eV). This is probably related to the strong relaxation and

reorientation of the organic cation (CH3NH3, CH2NHCH2) within the inorganic framework, resulting in pseudo-cubic structure (which is very close to a tetragonal structure), whereas the effect

of Cs on the crystal structure is small, maintaining the perfect cubic structure. * ii) In general, the band gap increases with an increase of electronegativity of the M and X ions: from I

to Br to Cl and from Pb to Sn. * iii) There is no general trend when considering the effect of the A cations. The effect of the A cations will be discussed in the following band structure

analysis. ELECTRONIC BAND STRUCTURES AND DENSITY OF STATES (DOS) To provide a better insight into the trends in the electronic structures of the nine AMX3 perovskites, we plot the electronic

band structures in Fig. 4. We group the compounds in terms of crystal structures and variations in only one of the ions (A/M/X): CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br, Cl) with a pseudo-cubic structure,

CH3NH3MI3 (M = Pb, Sn) in a tetragonal structure, CsMI3 (M = Sn, Pb) with an orthorhombic structure, ASnI3 (A = Cs, CH2NHCH2) with an orthorhombic structure. For CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I, Br, Cl)

with a pseudo-cubic structure, see Fig. 4(a), the band gaps and the trend in the increasing band gap when moving from I to Cl are in excellent agreement with experiments. The maximum

discrepancy is less than 0.02 eV, which is within the inherent accuracy of the methodology. The agreement of our results with experiments, especially for the cases of CH3NH3PbBr3 and

CH3NH3PbCl3, are better than in the work of Mosconi _et al_.11 using the GW method, where sizable overestimations were found for a tetragonal structure. This again highlights the importance

of the crystal structure of the studied materials when comparing with experiments. The common feature of all the simulated band structure are significant SOC effect with direct-indirect band

gaps. The substitution of I by Br (Cl) has little influence on the band dispersion of the CB (consisting mainly of Pb 6p states) but leads to sizable changes in the VB (consisting mainly of

halide _n_p states and to some extent of Pb 6 s states). More dispersion in the VB is found when substituting I by Br (Cl), evidenced by the downshifting of the bands at the Γ point (Fig.

4(a)). We pay special attention to two very important materials for photovoltaic applications, tetragonal CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3. Figures 4(b) and 5 show the band structures and densities

of states (DOS), respectively, together with a comparison with results from Umari10. As shown in Table 2, the band gap of 1.14 eV of CH3NH3SnI3 is in excellent agreement with the

experimental value of 1.21 eV and the GW value of 1.10 eV. Similar to the case of CH3NH3PbX3, the CB dispersion characteristics are almost unchanged. The substitution of Pb by Sn leads to a

slight shift of the CB to higher energy by about 0.03 eV (see Fig. 5). On the contrary, the VB maximum is shifted upwards much more strongly by about 0.67 eV and the band dispersion

increases (see the band dispersion between Γ and X, M and A, and at Z). These electronic structure differences between CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 agree nicely with experimental findings in

optical absorption spectra of a red-shift and an increased absorption intensity near the absorption onset42. In addition, our calculated DOS and band edge alignment is in good agreement with

results using the GW method by Umari _et al_.10: 0.67 (0.03) _vs_ 0.7 (0.2) eV for VB (CB) energy shifts. For CsMI3 (M = Sn, Pb) with an orthorhombic structure (Fig. 4(c)), a very similar

trend is found as for CH3NH3MI3 (M = Sn, Pb). The substitution of Pd by Sn leads to a smaller band gap. It should be noted that the DFT-1/2 band gaps of CsMI3 are slightly larger than those

of CH3NH3MI3: 2.00 (1.30) eV _vs_ 1.81 (1.14) eV for M = Pb (Sn). The difference in band gaps between CsMI3 and CH3NH3MI3 could be a result of variation in structures, unit cell sizes, and

the detailed interactions of the A, M, and I ions. Common explanations for the difference are counteracting each other. For example, the volume of the CsPbI3 unit cell is 7% smaller than

that of the unit cell of CH3NH3PbI3 (usually leading to a smaller band gap), whereas the degree of the tilting of the PbI6 octahedral framework in CsPbI3 is larger than that for CH3NH3PbI3

(usually leading to a larger band gap). While both the volume and the tilting of the octahedral framework of CsSnI3 are slightly smaller than those of the MASnI3by less than 2% (both usually

leading to a smaller band gap), the calculated band gap of CsSnI3 is in fact larger than that of CH3NH3SnI3. This unexpected result may be explained by taking into account the different

chemistry and interactions of Cs and CH3NH3 with the inorganic matrix of AMX3. As expected, for ASnI3 (A = Cs, CH2NHCH2) with an orthorhombic structure (Fig. 4(d)), the change of cation from

Cs to CH2NHCH2 yields almost no change in band dispersion and a slight band gap decrease. This is in agreement with one of the commonly accepted features of metal halide perovskites: the A

cation only weakly interacts with the inorganic matrix, with little electronic contribution at the band edges, and mainly plays a role in changing the volume of the lattice. The band gap

differences between CH2NHCH2SnI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 are again due to combinations of differences in unit cell volume (CH2NHCH2SnI3 > CsSnI3), tilting of the octahedral framework (CH2NHCH2SnI3

> CsSnI3), and chemical bonding characteristics. To summarize, our analysis emphasizes the fact that the electronic structure of AMX3 perovskites is a result of the interplay of several

properties: chemical environment, crystal structure, unit cell size, and thermodynamics of the materials. Therefore, an accurate electronic structure description of AMX3 perovskites requires

not only a reliable _ab-initio_ method but also a proper understanding of the interplay of several chemical and physical properties of the materials. In conclusion, we have applied an

approximate quasiparticle method, the DFT-1/2 method, to electronic structure calculations of AMX3 perovskites (A = CH3NH3, CH2NHCH2, Cs; M = Pb, Sn, X = I, Br, Cl) with several crystal

structures. Our results show that the DFT-1/2 method yields accurate band gaps showing very good agreement with experimental findings and results from the computationally much more demanding

GW method. Nevertheless, the computational cost is comparable to that of a standard DFT method. In addition, the trends in electronic structure properties were identified by varying only

one of the three A/M/X ions. In general, the band gaps increase with an increase in electronegativity of the M and X ion, and increase with a decrease of the symmetry of the crystal

structures: cubic < tetragonal < orthorhombic. There is no single applicable rule governing the trend in band gaps when only varying the A cation. Here, the interplay of several

aspects, such as unit cell size, crystal structure, chemical bonding, and thermodynamics of the material is decisive. Our work demonstrates the success of the DFT-1/2 method in predicting

the electronic structure of the AMX3 perovskites with minimal computational cost and opens the pathway towards studying large and complex structures in working devices and efficiently

designing new metal halide perovskite materials for solar cell applications. REFERENCES * Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as

visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 131, 6050–6051, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja809598r (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Im, J. H., Lee, C. R.,

Lee, J. W., Park, S. W. & Park, N. G. 6.5% efficient perovskite quantum-dot-sensitized solar cell. _Nanoscale_ 3, 4088–4093, https://doi.org/10.1039/C1NR10867K (2011). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide

perovskites. _Science_ 338, 643–647, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228604 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Saliba, M. _et al_. Incorporation of rubidium cations into

perovskite solar cells improves photovoltaic performance. _Science_ 354, 206–209, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5557 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Moser, J. E.

Perovskite photovoltaics: Slow recombination unveiled. _Nat. Mater._ 16, 4–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4796 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hutter, E. M. _et al_.

Direct–indirect character of the bandgap in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. _Nat. Mater._ 16, 115–120, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4765 (2017). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Azarhoosh, P., McKechnie, S., Frost, J. M., Walsh, A. & Van Schilfgaarde, M. (2016). Research Update: Relativistic origin of slow electron-hole recombination in hybrid halide

perovskite solar cells. _APL Mater._ 4, 091501, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4955028 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Even, J., Pedesseau, L., Jancu, J. M. & Katan, C.

Importance of spin–orbit coupling in hybrid organic/inorganic perovskites for photovoltaic applications. _J. Phys. Chem. Lett._ 4, 2999–3005, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz401532q. (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Brivio, F., Butler, K. T., Walsh, A. & Van Schilfgaarde, M. Relativistic quasiparticle self-consistent electronic structure of hybrid halide perovskite

photovoltaic absorbers. _Phys. Rev. B_ 89, 155204, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.155204 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Umari, P., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F.

Relativistic GW calculations on CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3SnI3 perovskites for solar cell applications. _Sci. Rep._ 4, 4467, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04467 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Mosconi, E., Umari, P. & De Angelis, F. Electronic and optical properties of MAPbX3 perovskites (X = I, Br, Cl): a unified DFT and GW theoretical

analysis. _Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys._ 18, 27158–27164, https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP03969C (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bokdam, M. _et al_. Role of Polar Phonons in the Photo

Excited State of Metal Halide Perovskites. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 28618, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28618 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Even, J., Pedesseau,

L., Jancu, J. M. & Katan, C. DFT and k· p modelling of the phase transitions of lead and tin halide perovskites for photovoltaic cells. _Phys. Status Solidi RRL_ 8, 31–35,

https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.201308183 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gao, W. _et al_. Quasiparticle band gap of organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites: Crystal structure, spin-orbit

coupling, and self-energy effects. _Phys. Rev. B_ 93, 085202, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.0852 02 (2016). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Huang, L. Y. & Lambrecht, W. R.

Electronic band structure, phonons, and exciton binding energies of halide perovskites CsSnCl3, CsSnBr3, and CsSnI3. _Phys. Rev. B_ 88, 165203, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.88.165203

(2013). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Castelli, I. E., García-Lastra, J. M., Thygesen, K. S. & Jacobsen, K. W. Bandgap calculations and trends of organometal halide perovskites.

_APL Mater._ 2, 081514, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4893495 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ferreira, L. G., Marques, M. & Teles, L. K. Approximation to density functional

theory for the calculation of band gaps of semiconductors. _Phys. Rev. B_ 78, 125116, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.78.125116 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ferreira, L. G.,

Marques, M. & Teles, L. K. Slater half-occupation technique revisited: the LDA-1/2 and GGA-1/2 approaches for atomic ionization energies and band gaps in semiconductors. _AIP Adv._ 1,

032119, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3624562 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. _Phys.

Rev._ 140, A1133, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1133 (1965). Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar * Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy

calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. _Comp. Mat. Sci._ 6, 15–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. _Phys. Rev. B_ 23, 5048, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.23.5048

(1981). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. _Phys. Rev. B_ 59, 1758,

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758 (1999). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Belabbes, A., Panse, C., Furthmüller, J. & Bechstedt, F. Electronic bands of III-semiconductor

polytypes and their alignment. _Phys. Rev. B_ 86, 075208, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.86.075208 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Slater, J. C. Statistical

exchange-correlation in the self-consistent field. _Adv. Quantum Chem._ 6, 1–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-3276(08)60541-9 (1972). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Slater, J. C.

& Johnson, K. H. Self-consistent-field X α cluster method for polyatomic molecules and solids. _Phys. Rev. B_ 5, 844, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.5.844 (1972). Article ADS Google

Scholar * Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. _J. Appl. Cryst._ 44, 1272–1276,

https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889811038970 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yamada, Y., Nakamura, T., Endo, M., Wakamiya, A. & Kanemitsu, Y. Near-band-edge optical responses of

solution-processed organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 on mesoporous TiO2 electrodes. _Appl. Phys. Express_ 7, 032302, https://doi.org/10.7567/APEX.7.032302/meta (2014). Article

ADS CAS Google Scholar * Chen, L. C. & Weng, C. Y. (2015). Optoelectronic Properties of MAPbI3 Perovskite/Titanium Dioxide Heterostructures on Porous Silicon Substrates for Cyan

Sensor Applications. _Nanoscale Res. Lett._ 10, 404, https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1114-x (2015). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Motta, C. _et al_.

Revealing the role of organic cations in hybrid halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3. _Nat. Commun_. 6, doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8026 (2015). * Poglitsch, A. & Weber, D. Dynamic

disorder in methylammoniumtrihalogenoplumbates (II) observed by millimeter‐wave spectroscopy. _J. Chem. Phys._ 87, 6373–6378, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.453467 (1987). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Weller, M. T., Weber, O. J., Frost, J. M. & Walsh, A. Cubic perovskite structure of black formamidinium lead iodide, α-[HC (NH2) 2] PbI3, at 298 K. _J. Chem. Phys.

Lett._ 6, 3209–3212, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01432 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Trots, D. M. & Myagkota, S. V. High-temperature structural evolution of caesium

and rubidium triiodoplumbates. _J. Phys. Chem. Solids_ 69, 2520–2526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Koh, T. M. _et al_.

Formamidinium tin-based perovskite with low E g for photovoltaic applications. _J. Mater. Chem. A_ 3, 14996–15000, https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA00190K (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Yamada, K. _et al_. Structural phase transitions of the polymorphs of CsSnI3 by means of rietveld analysis of the X-ray diffraction. _Chem. Lett._ 20, 801–804,

https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.1991.801 (1991). Article Google Scholar * Phuong, L. Q. _et al_. Free Carriers versus Excitons in CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Thin Films at Low Temperatures: Charge

Transfer from the Orthorhombic Phase to the Tetragonal Phase. _J. Phys. Chem. Lett._ 7, 2316–2321 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Papavassiliou, G. & Koutselas, I. Structural,

optical and related properties of some natural three- and lower-dimensional semiconductor systems. _Synth. Met._ 71, 1713–1714 (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ryu, S. _et al_.

Voltage output of efficient perovskite solar cells with high open-circuit voltage and fill factor. _Energy Environ. Sci._ 7, 2614–2618, https://doi.org/10.1039/C4EE00762J (2014). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Papavassiliou, G. C. & Koutselas, I. B. Structural, optical and related properties of some natural three-and lower-dimensional semiconductor systems. _Synth. Met._

71, 1713–1714, https://doi.org/10.1016/0379-6779(94)03017-Z (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar * Dimesso, L., Quintilla, A., Kim, Y. M., Lemmer, U. & Jaegermann, W. Investigation of

formamidinium and guanidinium lead tri-iodide powders as precursors for solar cells. _Mater. Sci. Eng. B_ 204, 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2015.11.006 (2016). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Koh, T. _et al_. Formamidinium-containing metal-halide: an alternative material for near-IR absorption perovskite solar cells. _J. Phys. Chem. C_ 118, 16458–16462,

https://doi.org/10.1021/jp411112k (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhumekenov, A. A. _et al_. Formamidinium lead halide perovskite crystals with unprecedented long carrier dynamics

and diffusion length. _ACS Energy Lett._ 1, 32–37, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00002 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * McMeekin, D. P. _et al_. A mixed-cation lead

mixed-halide perovskite absorber for tandem solar cells. _Science_ 351, 151–155, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5845 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Protesescu, L.

_et al_. Nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): novel optoelectronic materials showing bright emission with wide color gamut. _Nano Lett._ 15, 3692–3696,

https://doi.org/10.1021/nl5048779 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stoumpos, C. C., Malliakas, C. D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Semiconducting tin and lead

iodide perovskites with organic cations: Phase transitions, high mobilities, and near-infrared photoluminescent properties. _Inorg. Chem._ 52, 9019–9038 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Kitazawa, N., Watanabe, Y. & Nakamura, Y. Optical properties of CH3NH3PbX3 (X = halogen) and their mixed-halide crystals. _J. Mater. Sci._ 37, 3585–3587,

https://doi.org/10.1023/A: 1016584519829 (2002). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS S.X. Tao acknowledge funding by the Computational Sciences for Energy

Research (CSER) tenure track program of Shell, NWO, and FOM (Project number15CST04-2). The authors acknowledge Dr. Peter Klaver for technical support in the use of VASP and Dr. Ross Hatton,

Dr. Selina Olthof, and Prof. René Janssen for useful discussions. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Center for Computational Energy Research, Department of Applied Physics,

Eindhoven University of Technology, P.O. Box 513, 5600MB, Eindhoven, The Netherlands Shu Xia Tao, Xi Cao & Peter A. Bobbert Authors * Shu Xia Tao View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xi Cao View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Peter A. Bobbert View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS S.X.T. and P.A.B. conceived the project; S.X.T. implemented the DFT-1/2 method to calculate band structures, and

performed all DFT calculations. X.C. analyzed the results and made the figures and tables under the guidance of S.X.T. All authors contributed to the discussions and writing of the

manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Shu Xia Tao. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare that they have no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to

obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Tao, S.X., Cao, X. & Bobbert, P.A. Accurate and efficient band gap predictions of metal halide perovskites using the DFT-1/2 method: GW accuracy with DFT expense. _Sci Rep_ 7,

14386 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14435-4 Download citation * Received: 28 June 2017 * Accepted: 18 September 2017 * Published: 30 October 2017 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14435-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

He lost his home, but not his community | members onlyChristopher Fielden is no stranger to floods. Over the 18 years he’s lived in Swannanoa, North Carolina, 10 miles east o...

Tariffs could raise car prices, but there are still ways to saveFord recently announced a promotion that offers employee pricing on most 2024 and 2025 Ford and Lincoln models through J...

Can you get medicare supplemental insurance under 65?Memorial Day Sale! Join AARP for just $11 per year with a 5-year membership Join now and get a FREE gift. Expires 6/4 G...

The page you were looking for doesn't exist.You may have mistyped the address or the page may have moved.By proceeding, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and our ...

A father-son trip of a lifetime | members only_This essay, originally published in the June/July 2023 digital edition of_ AARP The Magazine, _won a Gold Award for Adv...

Latests News

Accurate and efficient band gap predictions of metal halide perovskites using the dft-1/2 method: gw accuracy with dft expenseABSTRACT The outstanding optoelectronics and photovoltaic properties of metal halide perovskites, including high carrier...

SOUTHERN OREGON STORIES: Janet L. NelsonSOPTV Stories of ServiceSOUTHERN OREGON STORIES: Janet L. NelsonClip: Season 1 | 6m 8sStudent at McKinley High School (n...

Kids now spend nearly as much time watching tiktok as youtube in us, uk and spain | techcrunchA new study on kids’ app usage and habits indicates a major threat to YouTube’s dominance, as kids now split their time ...

The eu's desire to punish britain is risking a no-deal brexit | thearticleThe EU brokered a Withdrawal Agreement with the UK and it is not prepared to renegotiate the deal, now that Britain is r...

Investment firms differ on lucent's outlook | rcr wireless newsWall Street has generally had a harsh view of Lucent Technologies Inc. The company’s stock is trading near its 52-week l...