Religion and educational mobility in africa

Religion and educational mobility in africa"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The African people and leaders1,2 have long seen education as a driving force of development and liberation, a view shared by international institutions3,4, as schooling has large

economic and non-economic returns, particularly in low-income settings5. In this study, we examine the educational progress across faiths throughout postcolonial Africa, home to some of the

world’s largest Christian and Muslim communities. We construct comprehensive religion-specific measures of intergenerational mobility in education using census data from 2,286 districts in

21 countries and document the following. First, Christians have better mobility outcomes than Traditionalists and Muslims. Second, differences in intergenerational mobility between

Christians and Muslims persist among those residing in the same district, in households with comparable economic and family backgrounds. Third, although Muslims benefit as much as Christians

when they move early in life to high-mobility regions, they are less likely to do so. Their low internal mobility accentuates the educational deficit, as Muslims reside on average in areas

that are less urbanized and more remote with limited infrastructure. Fourth, the Christian–Muslim gap is most prominent in areas with large Muslim communities, where the latter also register

the lowest emigration rates. As African governments and international organizations invest heavily in educational programmes, our findings highlight the need to understand better the

private and social returns to schooling across faiths in religiously segregated communities and to carefully think about religious inequalities in the take-up of educational policies6.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE EFFECT OF INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY ON FAMILY EDUCATION INVESTMENT: EVIDENCE FROM CHINA Article Open access 25 September 2023 EARLY CHILDHOOD

CIRCUMSTANCES AND EDUCATIONAL WELLBEING INEQUALITY AMONG TRIBAL AND NON-TRIBAL CHILDREN IN INDIA: EVIDENCE FROM A PANEL STUDY Article Open access 14 June 2022 DOES GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION

IMPACT EDUCATIONAL DISPARITIES AMONG ECUADORIANS? A NOVEL TWO-STAGE INEQUALITY DECOMPOSITION METHOD Article Open access 14 November 2024 MAIN Africa hosts vibrant Christian and Muslim

communities and, given the demographic trends, it will be home to the largest numbers of both creeds in the coming decades7. Religiosity is high, with 75% of Christians and Muslims attending

a church and a mosque at least once a week, according to the 2016 Afrobarometer Surveys. Nevertheless, the most important divide between African Muslims and Christians is not their

religion. As we show here, educational gaps circumscribe the religious landscape. This is not a recent phenomenon. At independence, Christians enjoyed more schooling, reflecting colonial

investments and missionary activity8,9,10. In several countries, mostly in West Africa, primary school completion for Christians was more than double that of Muslims or Africans adhering to

local religions (Supplementary Information, section A). Although the share of Africans with no schooling has declined from two-thirds for those born in the 1950s to less than half for the

1990s cohort, religious differences persist. For example, in Nigeria (Africa’s most populous country, roughly equally split between Christians and Muslims), the primary school completion

rate of Christians is 0.88, whereas it is 0.57 for Muslims. In Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous country, 29% of Christians (about two-thirds of the population) born in the 1990s have

completed primary education, with Muslims registering 16%. African Muslims are more educated only in a few countries where they are small minorities—South Africa, Zambia and Rwanda (about

1–2% of the populations of these countries) and Uganda (11%). Policy briefs and reports7,11 have discussed the considerable Muslim–Christian differences in education levels but a

comprehensive account of the evolution of interdenominational educational gaps and their determinants is missing. Although some pioneering case studies analyse the role of religion in

Nigeria12,13, looking among others at the Yoruba14,15, there has been limited comparative work on religion, as the vibrant research in economics on the political economy of African

development mainly focuses on ethnicity16,17,18. Similarly, research on the interplay between religion and economic performance19,20 often focuses on the role of Islam in the Middle East and

Asia21. It is in Africa, though, that the interreligious gaps in education are striking and a plethora of narratives point to their rising salience22. An exception is the parallel work of

refs. 23,24, who report considerable educational differences between Christians and Muslims in 11 African countries in 2017, showing further that gaps are considerable in predominantly

Muslim areas. Focusing on Malawi, Nigeria and Uganda, these studies stress the role of religious leaders and social norms. Most importantly, the considerable body of research quantifying the

role of educational reforms and government policies in the continent has not considered the role of religion25. Likewise, recent works mapping the intergenerational transmission of human

capital across countries26,27, US states28, Chinese provinces29 and African regions30,31,32 do not study the role of religion. Others33 explore regional, caste and religious differences in

intergenerational mobility in education (IM; also referred to as educational mobility) across India; and like us, they uncover lagging educational mobility for the Muslim population, which

contrasts with the rising mobility among the low socioeconomic status castes. We construct statistics on faith-specific IM across 21 African countries and 2,286 regions and uncover

substantial differences between Muslims, Christians and Africans adhering to Traditional (Folk) religions (Animists). (We use the terms Traditionalists and Animists interchangeably

throughout). We then trace the roots of these disparities. Interreligious differences in education levels at independence explain a substantial fraction of the observed variation.

Nevertheless, even when we compare young Africans living in the same district with similarly (un)educated elders in their religious group, in households of comparable size and structure and

in which the household head works in the same broad sector and occupation, IM gaps, albeit attenuated, endure. Muslim children underperform in regions where they are numerous compared to

where they are a minority, a pattern that is not present for Christians and adherents of Traditional religions. Muslims benefit as much as Christians when they move early in life to high-IM

regions. Given the explanatory power of religious segregation and the impact of regions on adherents of all creeds, we conclude with a primer on internal migration differences. Christians

are much more likely to emigrate and exploit opportunities outside their birthplace in almost all countries. The low propensity of Muslims to move accentuates their initial educational

disadvantage, as they typically reside in remote places, far from the capital and the coastline, with limited missionary activity and transportation investments. Muslims register the lowest

emigration rates and largest IM deficits in these religiously segregated areas. DATA AND EDUCATIONAL MOBILITY STATISTICS We construct measures of IM across 2,286 districts in 21 African

countries using information from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) International, which collects and harmonizes censuses, reporting representative (typically 10%) samples

(see ‘Data availability’ in Methods). As the detail of religious denomination differs across censuses, we aggregate into Muslims, adherents of Traditional religions, Christians and two

auxiliary categories (Other and No Religion). Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1 give the shares in our 21-country sample (see also Data section). Our measures of educational IM

reflect how children fare vis-a-vis their cohabiting elder members, mainly parents, in the household. We use primary school completion as the critical educational milestone for Africans born

up until the 1990s, as secondary and college enrolment has increased mainly since the 2000s (Supplementary Fig. A2). Upward IM denotes the likelihood that 14–18-year-old children whose

parents have not completed primary education manage to complete primary school; downward IM gives the likelihood that 14–18-year-old individuals whose parents have completed primary

education will not manage to finish primary school. Our base sample consists of 7,188,717 children between 14 and 18 years of age. We also look at 14–25-year-old children as the sample

increases to 13,018,904 with cohabitation rates of about 75%. We provide details in the Data and educational IM measures section and in Supplementary Information, section B. RELIGIOUS IM

ACROSS AFRICA COUNTRY PATTERNS Table 1 reports the newly constructed faith-based IM statistics across countries, the Christian–Muslim gaps in upward and downward IM and their level of

statistical significance (Supplementary Information, section C provides additional measures.) With the exception of Mozambique, upward IM is lowest for Africans adhering to Traditional

religions (column 4 of Table 1); it is less than 10% in Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Malawi, Uganda and Ethiopia. Upward IM is low for Traditionalists, even in countries with

considerable representation. For example, in Togo where overall IM is 52.6%, Animists register 38.2%; and in Benin their 21.3% IM trails the country average by 8.5 percentage points.

Christians enjoy the highest upward IM in 15 out of the 21 countries with a cross-country mean of 41.2%. The IM of Muslims exceeds that of Christians in South Africa (87.4% versus 74%),

Zambia (47.6% versus 44.5%, although this difference is not significant at standard confidence levels) and Rwanda (27.4% versus 18.3%), where their shares are tiny (0.8–1.5%) and in Uganda

(48.5% versus 40.4%), Mauritius (96% versus 87.8%) and Liberia (26.6% versus 21.8%), where Muslims constitute between 10% and 16% of the population. The Christian–Muslim gap in upward IM is

considerable in many countries. In Nigeria, Muslim children of illiterate parents are 32 percentage points less likely to complete primary schooling than Christian children born to similarly

uneducated parents (78.6% versus 46.6%). In Ethiopia, a country with very low primary school completion rates, the upward IM for Christians is 13.8%, whereas for Muslims it is 8.2%. The

Christian–Muslim upward IM gap is largest in West Africa (that is, the mean is 22.1%), where Muslims form the majority (Guinea, Senegal and Burkina Faso) or substantial minorities (Nigeria,

Benin, Cameroon and Ghana). Downward IM is high for Muslims (the mean is 27.5%) and Traditionalists (the mean is 42.6%). In West Africa, roughly one out of six Muslim children born to

parents who completed primary schooling will fail to do the same. In Cameroon, the downward IM is 4.1% for Christians and a staggering 19.6% for Muslims. Downward IM for Nigerian Muslims is

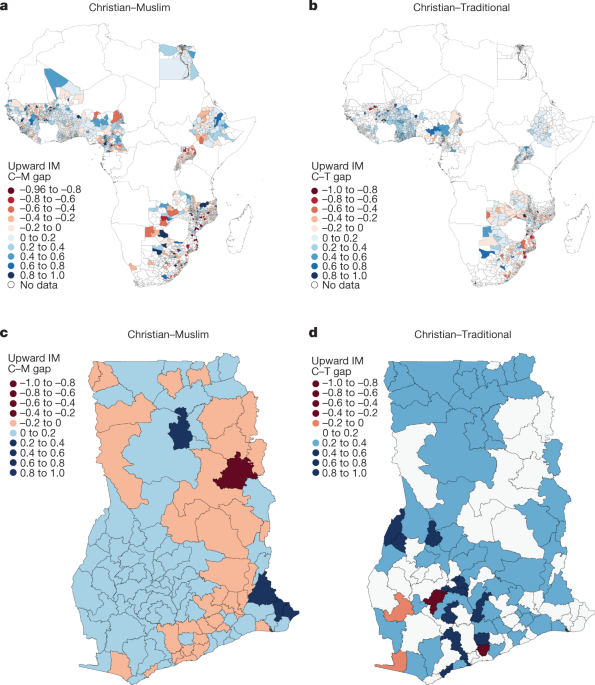

twice that of Christians (16.2% versus 7.8%). This pattern is reversed in countries with small Muslim communities. REGIONAL PATTERNS Figure 1a portrays, for the 1980 and 1990 birth cohorts,

the gap in upward IM between Christians and Muslims and Fig. 1b between Christians and adherents of Traditional religions across 1,731 and 1,071 African districts, respectively.

(Supplementary Table C3 summarizes the districts’ population and land area. Within countries, Muslim-majority districts are comparable in area to Christian). The depicted districts are fewer

than the total number of districts as we need to observe in each district 14–18-year-old individuals born in the 1980 and 1990 cohorts from both religions. Figure 1c,d zoom into Ghana to

illustrate the within-country variation. The Christian–Muslim gap is large in West Africa. (Supplementary Fig. C1 maps upward IM for Christians, Muslims and Traditionalists, respectively).

Extended Data Table 2 reports regional statistics. Within-country variation is notable in Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Ethiopia. Christians fare better than Muslims in almost all the

districts of Senegal and Burkina Faso, despite the numerical dominance of Muslims. In Ghana and Cameroon, the upward IM of Christians exceeds that of Muslims in three out of four districts.

The Christian–Muslim upward IM gap is lower in the southern districts of West African countries, an issue we return to in the section on Religious IM across Africa. Educational outcomes for

Muslims, Traditionalists and Christians move together as the cross-region correlation of religious upward IM is 0.60–0.72 and for downward IM 0.39–0.62 (Supplementary Table C6). However,

Muslims and Traditionalists underperform compared to Christians, even when we zoom in on the same district. In the median region, upward IM for Christians is 0.44, 0.33 for Muslims and 0.21

for Traditionalists. Downward IM for Christians is 0.25, for Muslims 0.29 and 0.35 for Traditionalists (Supplementary Table C4). EXPLAINING THE RELIGIOUS IM GAPS APPROACH We estimate

individual-level regressions that associate the IM of children with their own religious affiliation, using Christians as the omitted category. We drop ‘other religion’ and ‘no religion’ as

these are not comparable across censuses and countries. A large body of research documents non-negligible differences in family arrangements, age of marriage, social practices and

occupational specialization between Christians, Muslims and adherents of Traditional religions (Animists). To explore their role, we examine how the estimates on the Muslim and the

Traditional religion indicators change as we account for: (1) household size and family structure variables, including the age of marriage; (2) proxies of household income (as, for example,

the profession and the industry of employment of the household head); (3) the literacy of the older generation for the individual’s coreligionists in the district; and (4) district constants

interacted with urban–rural household status. These features may interact or be jointly determined by deeper factors. Our objective is not to identify causal effects but to examine the

fraction of the variation in educational mobility gaps explained by these aspects. Figure 2 reports ordinary least-squares (OLS) estimates weighting by the population of a country to account

for differences in IPUMS coverage, whereas Extended Data Fig. 2 reports country-specific estimates of Christian–Muslim differences. (Supplementary Information, section D gives results for

various data subsets). BASELINE IM GAPS The top bars simply condition on country cohort fixed effects and children’s age constants to account for the increase in education over time. Among

children whose parents have not completed primary education, Christians enjoy an advantage of 16 percentage points in completing primary school over Muslims and 20 percentage points over

adherents of Traditional religions born in the same decade and country. Muslim children whose parents have completed primary education are 7 percentage points less likely than Christians to

achieve the same qualification. If anything, Traditionalists have a lower rate of downward mobility than Muslims. HOUSEHOLD STRUCTURE AND SIZE We condition on a rich set of household

features: (1) size, distinguishing between individuals of the generation of the young, the head and the grandparents; (2) indicators for each 14–18-year-old individual regarding his/her

relationship to the household head (for example, biological children, relative, nephews, spouse); (3) family organization indicators (for example, father and mother present, father or mother

only, others only); and (4) mother’s and father’s age at their offspring’s birth. We include all variables concurrently, as our objective is not to identify the most relevant one but to

examine how much the religion coefficients move when we account for a saturated set of household traits. As we show in Supplementary Information, section D, there are important

interreligious differences in household features. Muslim and Animist households are, on average, larger; 14–18-year-old Muslim girls are more likely to be spouses of the household head than

Christian girls of the same age; and Muslim and Animist parents are, on average, younger at their children’s birth than for Christians, reflecting earlier marriages. Despite these

differences in the family organization, the educational gaps do not move much when we account for the former. The upward IM gap drops from 0.165 to 0.15 for Muslims and from 0.20 to 0.18 for

adherents of Traditional religions. Household structure and size play a somewhat bigger role in narrowing the Christian–Muslim IM gap in West Africa but their influence is negligible in

East and Southern Africa (Extended Data Fig. 2). Downward IM differences between Muslims and Christians are more affected by the inclusion of the rich set of household controls closing the

overall gap by roughly 20% from 0.07 to 0.055. HOUSEHOLD AND PARENTAL OCCUPATIONAL DIFFERENCES We then turn to economic features, conditioning in model 3 of Fig. 2 on the following three

(sets of) attributes (1) urban versus rural residence; (2) the industry of employment (six categories); and (3) the occupational specialization (ten categories) of the household head. As

shown in Supplementary Information, section D, adherents of Traditional religions are more likely to live in rural areas (20%) and work in agriculture and are less likely to be professionals

or skilled employees. Christian–Muslim differences in the employment industry, rural–urban status and profession are minor, perhaps masking larger ones owing to the coarse aggregation of

IPUMS. In line with these patterns, differences between Christians and Muslims in living conditions and access to necessities in Afrobarometer Surveys and household income in the surveys7

are also small (although Muslim households are larger). Variations in the industry of employment (broadly defined), occupation and urban–rural residence explain a non-negligible component of

the IM differences between Christians and Traditionalists: the upward IM gap drops from 0.20 to 0.15 and the downward IM gap halves. These economic features do not explain the

Christian–Muslim IM upward gap. If anything, the downward mobility gap becomes more pronounced when we compare children born in households of similar occupational structures. INITIAL

LITERACY In model 4 of Fig. 2, we control for the share of the older generation with completed primary education in the district for each religious group. This accounts for initial,

group-specific regional development and schooling, stemming from the location of Christian missionaries, colonial educational investments and the spread of Islam34. The Christian–Muslim

upward IM gap drops from 0.15 to 0.085. Likewise, the Christian–Muslim downward IM gap goes from 0.07 to 0.04, whereas the Christian–Traditionalist downward IM is eliminated. Differences in

religious literacy rates of the older generation across districts seem first order, consistent with our earlier work31, showing that initial literacy is the most important correlate of

regional IM. REGIONAL FEATURES As recent studies30,31,32 show that regions have a chief role in educational mobility, in model 5 of Fig. 2, we augment the specification with

district-specific constants interacted with urban indicators (the interaction with the urban indicator does not affect the estimates). Regions explain a non-negligible fraction of the IM

gaps, as there is considerable segregation across most African countries35 and Muslims (and Traditionalists) reside in places with low opportunity (see below). The coefficient on the

indicator for Traditional religions in the upward IM specification is not much affected (stays around 0.08), whereas the downward IM gap is eliminated. Accounting for regional features

reduces the Christian–Muslim upward IM gap to 0.05 and the downward IM to 0.03. The explanatory power of regions for the Muslim–Christian mobility gaps seems first order in many countries,

mainly in West Africa, where religious segregation is the highest (Extended Data Fig. 2). In Benin, Cameroon, Ghana and Senegal, the Christian–Muslim gap in upward IM halves when we account

for residence (and initial differences in literacy). In Nigeria, the upward IM gap drops from 0.30 to 0.10, whereas in Mozambique, it goes from 0.08 to nil. This pattern echoes the patterns

across India36 of considerable heterogeneity in relative educational mobility across castes and religions in narrow geographic areas. In the last row, we restrict estimation to half of the

regions where interreligious differences in completed primary education of the older generation are the smallest to better account for ‘initial’ conditions in the district. The

Christian–Muslim gap in upward IM continues to be close to 5 percentage points and 2 percentage points for downward IM. TAKING STOCK The analysis shows the following. First, differences in

household structure between Muslims and Traditionalists, on the one hand, and Christians, on the other, explain a small fraction of educational mobility differences. Second, broad economic

features have no role in the Christian–Muslim upward gap but reduce the Christian–Animist difference. Third, the literacy of the older generation in the district for each religious group and

region-specific features explain roughly two-thirds of the interreligious IM gaps; this is especially the case in West Africa, where segregation is the highest. Fourth, Christian–Muslim

educational gaps remain, even when we compare children with the same parental background and family composition residing in the same region (with comparable literacy rates in the older

generation of the various religious groups). SORTING AND CHILDHOOD REGIONAL EXPOSURE The prominence of regions gives rise to a plethora of questions ranging from their independent impact on

the educational IM of the different denominations to unpacking the relevant regional characteristics. In this section, we address the former and, in the next section, the latter.

Supplementary Information, section E gives descriptive statistics and further evidence. EMPIRICAL DESIGN To isolate regional childhood exposure effects from spatial sorting, we use the

approach of refs. 37,38 and leverage differences in the age of children’s moves across districts39. The specification, detailed in the Methods, associates primary school completion for

children of uneducated parents (upward educational IM) with the age of children’s move and differences in educational mobility between birthplace (_o_) and destination district (_d_) among

non-movers of the same cohort _b_\([{\varDelta }_{odb}=\overline{{\rm{IM}}}\_{{\rm{up}}}_{bd}^{{\rm{nm}}}-\overline{ \% \,{\rm{IM}}}\_{{\rm{up}}}_{bo}^{{\rm{nm}}}]\).

\(\overline{{\rm{IM}}}\_{{\rm{up}}}_{b}^{{\rm{nm}}}\) summarizes all features of the economic, social, educational and institutional environment, shaping IM in a given district. These could

reflect, among many others, local returns to schooling, school quality and quantity, accessibility, schooling fees and teacher–pupil ratios that differ considerably in low-income

countries40.The age-specific parameters on destination minus origin IM, \({\beta }_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}\), capture how a child’s probability of completing primary schooling varies with the age

of their move to districts with higher or lower mobility. If regions matter for mobility, the earlier the move, the greater the impact. The variation comes from children born in the same

place and decade moving to regions with different IM. Differences in the age-of-move slopes reflect the impact of an extra year in the high IM district—regional childhood exposure effects.

The main identifying assumption, backed by our earlier work31, is that the timing of moving for households is unrelated to children’s ability. SAMPLE Not all censuses record the age of the

move. These estimates come from a sample of 276,686 14–25-year-old individuals from 13 countries. These countries come from all major African regions; they are both former British and French

colonies and non-colonized (Ethiopia); relatively poor and rich. RESULTS Figure 3 plots the age-of-move estimates, \({\hat{\beta }}_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}\), for Christians and Muslims against

the child’s age at the time of the household move. In Fig. 3a,b, origin–destination upward IM differences are calculated using all non-movers independently of religious affiliation, whereas

in Fig. 3c,d, we use non-movers of the same religious group. The estimates for Traditionalists (not reported) are similar but imprecise, reflecting the small sample and the blending of

heterogeneous religions. The figure uncovers two sets of patterns. First, the age-of-move slopes, \({\hat{\beta }}_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}\), are large for early-in-life moves and decline until

around the age of 12–14 years. Children moving to ‘better’ districts earlier in life have a higher propensity to complete primary schooling. The relationship between age at move and exposure

is negative and approximately linear, implying ‘regional childhood exposure effects’: moves in higher (lower) mobility districts are beneficial (detrimental) for younger kids. A further

year of exposure before the age of 12 years for a child of illiterate parents to higher mobility district increases her chances for completing primary school by roughly 2 percentage points.

Exposure effects are also 2% for Muslims and Christians when we compare them to their coreligionists. Both Muslim and Christian children benefit (lose) from early moves into high (low)

upward mobility regions. Extrapolating over 14 years of childhood, Muslim and Christian children who move at birth to a district with one percentage point higher upward IM among Muslims will

pick up roughly 30% of this difference through the impact of the region. Second, the slopes are significantly positive, even for children moving after 13–14 years. As moves after that age

are unlikely to affect primary education, they reflect selection. Parametric specifications imposing a piecewise linear structure of exposure effects from 1 to 11 and from 12 to 18 yields

similar regional childhood exposure estimates for Christians and Muslims. Besides, within-household specifications exploiting variation in the time of move across siblings also yield

regional childhood exposure effects of about 2% for both faiths (Supplementary Information, section E). TAKING STOCK We obtained two results: (1) although spatial sorting is considerable,

children whose families move earlier to areas where residents (of all faiths or of their religion only) have higher IM are more likely to complete primary school and (2) regional childhood

exposure effects are comparable for Christians and Muslims. RELIGIOUS IM GAPS ACROSS AFRICAN REGIONS Why do region-specific constants explain roughly half of the religious IM gaps? There are

two possible explanations: (1) religious segregation, coupled with regional differences in educational opportunity, arising, for example, from more accessible and better-quality schools,

make upward mobility more challenging for Muslims and adherents of Traditional religions and (2) the same regional feature may influence followers of different religions differently.

DIFFERENCES IN RESIDENCE ACROSS FAITHS In Methods and in Extended Data Fig. 3 we explore how the residence characteristics compare across religious groups. On average, Muslims and

Traditionalists reside in regions that, at the end of the colonial period, were less densely populated and more agriculture-oriented than Christians. Besides, Muslims and Traditionalists

reside away from the capitals and the coastline; they live in districts with fewer colonial investments, away from colonial railroads, roads and Christian missions. Consequently, the lower

representation of Muslims in regions with better initial conditions is of first-order importance for explaining the observed Christian–Muslim IM gap. APPROACH We estimate within-country

district-level specifications associating regional Christian–Muslim and Christian–Animist differences in upward IM to various regional characteristics. Figure 4 reports standardized

coefficients. As the literacy rate of the older generation is the strongest correlate of IM (Fig. 2), we also run specifications conditioning on it (Extended Data Fig. 6). Extended Data

Figures 4 and 5 present regional specifications separately for adherents of Christianity, Islam and Traditional religions and compare the magnitudes of the coefficients. Although the

analysis does not have a causal interpretation, it allows for characterizing the geography of the considerable variation in religious educational IM within countries. Besides, it complements

the evidence in Fig. 3, as the movers’ design that distinguishes spatial sorting from childhood exposure effects does not pin down which regional features correlate with religious IM. EARLY

DEVELOPMENT, HISTORICAL INVESTMENTS AND GEOGRAPHY Drawing on research on the roots of African development41, we start examining the role of geographic, historical and at-independence

features. As Extended Data Fig. 4 shows, upward IM is higher and downward IM is lower in more densely populated and urbanized regions, more specialized in services and manufacturing, close

to the capitals, the coast and missionary activity and transportation infrastructure. However, these features do not explain the Christian–Muslim and the Christian–Traditionalist IM gaps, as

the correlations are similar across groups. SEGREGATION We then turn to religious fragmentation and segregation. Our exploration is motivated by three observations. First, religious IM gaps

are larger in segregated countries and Muslim educational mobility is the highest in countries with small Muslim communities. Second, US-centred research shows that racial segregation moves

in tandem with underinvestments in education42,43. Third, recent work44 shows that Muslims underperform (in education and health) in areas with precolonial Islamic states (for example, in

Northern Nigeria and Cameroon and Senegal) owing to weak penetration of the colonial state and limited public-goods investments by missionaries. By contrast, in areas with modest Muslim

communities, religious competition pushed Muslims (elites) to adopt Western education. Figure 4d looks at the association between the IM gaps and religious composition. Diversity, as

captured by the Herfindahl index, is not a significant correlate. But the religious upward IM gaps are strongly correlated with segregation. The Christian–Muslim upward IM gap is

significantly higher (lower) in predominantly Muslim (Christian) regions; Muslims underperform in districts where they are majorities. Evidently, the share of Muslims in the district is the

strongest correlate of the Christian–Muslim upward IM differences. Figure 5 further unpacks this association. Figure 5a plots the Christian–Muslim gap in upward IM against the fraction of

Muslims across districts, whereas Fig. 5b conditions on the religion-specific literacy rates of the older generation in the district that correlates strongly with IM. The strong positive

association remains intact. Figure 5c,d plot the correlation between upward IM and own-religion share separately for Christians and Muslims, conditioning on the literacy of the elders. The

likelihood that Christian children of parents without much education will complete primary school is similar in places with small, modest and prominent Christian communities. By contrast,

completion of primary education for Muslims is high in regions with small Muslim communities but (very) low in (predominantly) Muslim districts. The negative association between educational

opportunity and own-religion share for Muslims echoes US-based evidence that African American children underinvest in education in segregated communities and ghettos. Besides, it squares

with India-based results36, showing a negative association between caste segregation and relative educational mobility. TAKING STOCK We arrived at two takeaways. First, for all faiths,

upward IM is higher and downward IM is lower in more developed regions, closer to the capital and the coast, with relatively more colonial investments. However, as Muslims and adherents of

Traditional religions reside in less developed, more remote regions with less colonial infrastructure, they are at a disadvantage. Second, religious segregation seems instrumental (although

the correlations do not identify causal effects). Christians do well independently of residence, whereas Muslim children underperform compared with other coreligionists in areas where

Muslims seem in greater numbers, even when we account for differences in the literacy of the older coreligionists in each district. INTERNAL MIGRATION Motivated by the evidence on regional

childhood exposure effects for both Muslims and Christians (Fig. 3) and the significant correlation between segregation and religious IM gaps (Fig. 5), we zoom in on internal migration.

DIFFERENTIAL INTERNAL MIGRATION We tabulate internal migration rates by religious affiliation. We classify as migrants those individuals who, at the time of the census, reside elsewhere than

their birthplace district. Figure 6a plots the internal migrant shares for Christians, Muslims and Traditionalists, pooling all censuses across 20 countries (data unavailable for Nigeria).

In Fig. 6a and 6b we indicate whether the probability of migration is significantly different between Christians and Muslims in each country. In 17 countries, Christians move at higher rates

than Muslims. On average the propensity of Christians to migrate is 0.298 compared to 0.222 for Muslims and 0.194 for Traditionalists. In Cameroon, 40% of Christians reside somewhere other

than their birthplace district, whereas the corresponding share for Muslims is 25%. In Ethiopia, the Christian–Muslim difference in emigration is 7 percentage points, whereas in Malawi it is

15 percentage points. The emigration rates of Muslims exceed those of Christians only in Rwanda (by 10.8 percentage points), Uganda (by 4.3 percentage points) and Mozambique (by 0.9

percentage points). Migration decisions reflect the associated costs and benefits of doing so that may differ across religious lines. Muslims probably face higher migration costs as they

reside in relatively remote regions with limited investments. Thus, in Fig. 6b, we report internal migration shares, netting out the mean at the individual’s birthplace (weighted by the

population of the region in the country) to account for interreligious differences in residence (Extended Data Fig. 3). Differences in internal migration are evident, even when we compare

individuals born in the same district, with Christians being 3.6 percentage points more likely to move out than Muslims. Only in Uganda, South Africa, Mozambique and Rwanda, where Muslims

are in the minority, are they on average 4 percentage points more likely to move from their birth region compared to Christians. Which other factors shape the uncovered differences,

economic, cultural or institutional (interacted with religion), remains uncertain45,46,47. MIGRATION AND RELIGIOUS SEGREGATION Motivated by the low educational mobility of Muslims in

predominantly Muslim districts, we explored the association between migration propensity and religious segregation. Figure 7 illustrates the patterns, plotting internal migration rates for

Christians and for Muslims against their own-religion population shares. The (within-country) association is negative for both religious groups but starker for Muslims. The correlation

between internal migration and own population share in the birthplace is three times larger for Muslims (coefficient (standard error) −0.33 (0.0248)) than for Christians (estimate (standard

error) −0.12 (0.0234)). Muslims, compared to Christians, have a much lower propensity to move out of regions with sizable Muslim communities, exacerbating their initial educational

disadvantage. DISCUSSION We construct religion-specific educational mobility measures since independence across African countries and regions and explore their origins. Three regularities

emerge. First, there are significant differences in IM between Christians and Muslims, even comparing Africans living in the same district, with similarly (un)educated elders in their

religious group, in households with comparable size and structure and with household heads in the same broad sector and occupation. Second, although Muslims benefit as much as Christians

when they move early in life to high-mobility regions, they seem less likely to do so. The comparatively low internal mobility of Muslims accentuates their educational IM deficit, as they

(and Traditionalists) reside in less urbanized areas, far from the capital and the coastline areas with limited infrastructure. Third, in areas with large Muslim communities, the

Christian–Muslim IM gap is greatest; these highly segregated areas also have the lowest emigration rates among Muslims. Our study begets more questions than it answers. First, as there is a

great deal of variation within faiths, research should explore within-denomination variation distinguishing, for example, between Maliki and Shafi Suni, Ahmadis and Shia Muslims and between

Protestants, Copts and Catholics. Doing so would allow delving into the probable causes, teasing apart the role of (1) social norms, (2) faith-specific schooling infrastructure, including

_maktabs_ and _madrasas_ for Muslims and (3) religious leaders and their interaction with state institutions24,44,45. Second, our measures of intergenerational mobility in education do not

capture how much learning takes place in schools and recent studies stress the low quality of schooling in the continent48,49. This may partially rationalize why the first-order differences

in education between African Christians and Muslims do not translate into a stark interfaith gap in well-being and occupational specialization. It also highlights the need to estimate

faith-specific private and social returns to schooling, both actual and perceived50, in religiously segregated labour markets with denomination-specific risk-sharing institutions. The

voluminous literature we review in Supplementary Information, section A1, documenting higher returns to primary education in low-income settings and Africa in particular5,6, has paid little

attention to the role of religion. Third, as millions are moving to Africa’s new megacities, research should explore, and policy-makers should rethink, potential heterogeneity along

religious lines of the economic return to migration, linking it with migration costs and labour markets both at the origin and the destination. Finally, as international institutions and

African governments invest heavily in education with school construction programmes, abolishing fees and expanding access and georeferenced data on schools, educational quality and learning

become available40,51, future work on educational reforms needs to carefully explore the roots of inequalities in the take-up of educational policies by religious groups25. METHODS DATA AND

EDUCATIONAL IM MEASURES DATA REPORTING No experiments were performed. No statistical methods were used to predetermine the sample size of the harmonized census data provided by IPUMS.

Supplementary Information, section B1 details our procedure for going from the IPUMS data to the sample used in the empirical analysis. DATA IPUMS International records religious affiliation

in 45 censuses from 20 African countries plus Nigeria, for which data come from household surveys between 2006 and 2010. The spatial disaggregation allows us to analyse a maximum of 2,304

districts, typically admin-2 or admin-3 regions. The number of districts used to construct faith-specific IM measures varies by cohort and whether one imposes restrictions in terms of

sampling. (See also Supplementary Tables C4 and C5 and the discussion in Supplementary Information, section C3) Extended Data Table 1 reports religious shares by country. Egypt, Senegal,

Mali and Guinea are predominantly Muslim (shares exceeding 85%), as well as Sierra Leone (77%) and Burkina Faso (59%). The share of those following Traditional religions is substantial in

West Africa, Togo (29%), Benin (22%) and Burkina Faso (19%). When we weigh by the population of a country to account for the limited observations from Nigeria, Christians are about 50%,

Muslims 42.7% and Traditionalists about 3% (Extended Data Fig. 1). We discuss conversion dynamics and their implications for IM in educational attainment estimates in Supplementary

Information, section B3. SAMPLE REPRESENTATIVENESS In 2020, the 21 countries hosted roughly 750 million of Africa’s 1.35 billion people. North Africa is under-represented, as we have data

only from Egypt. The sample includes both relatively rich, educated, with strongly institutionalized countries (for example, South Africa and Botswana with gross domestic product (GDP) per

capita of about US $4,000–4,500 in 1995) and relatively poor, weakly institutionalized countries (for example, Ethiopia, Malawi and Mozambique with GDP per capita of about US $250 in 1995).

The sample includes former British (Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Malawi), French (Burkina Faso, Senegal and Guinea), German-Belgian (Rwanda) and Portuguese (for example, Mozambique) colonies

and protectorates, besides Liberia and Ethiopia. The sample also includes low-state capacity countries with lasting civil wars (Sierra Leone, Mozambique, Rwanda, Liberia and Ethiopia) and

more stable ones (South Africa and Botswana). Supplementary Information, section B5 shows that the 21 countries are representative of the continent. INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY Our measures

of educational IM reflect how 14–18-year-old children fare vis-a-vis cohabiting older generation members, typically biological parents, using primary school completion as the critical

educational milestone (Supplementary Fig. A2). Absolute upward IM in education: IM_up_igbcrt_ = 1 in the case of child _i_, of religious affiliation _g_, born in decade _b_ in country _c_

(and residing in region _r_), observed in census-year _t_, born to parents who have not completed primary schooling completes primary education. Absolute downward IM in education:

IM_down_igbcrt_ = 1 in the case of child _i_ whose parents have completed primary schooling does not complete primary education. The IPUMS codebooks suggest that attendance at Christian and

Islamic schools is accounted for as long as they do not solely cover religious topics. EDUCATIONAL DYNAMICS AND IM The literature on IM uses various statistics52, like (one minus) the

intergenerational coefficient obtained from a regression of children on parental schooling53, rank–rank coefficients and rank movements29. Other studies54,55,56,57 focus, as we do, on

absolute transitions. Absolute mobility reflects both overall increases in education over time and movements in the distribution; hence relative and absolute IM measures are not necessarily

correlated. See refs. 58,59 for a discussion on the link between absolute IM, relative IM, inequality and growth. We compile new statistics and study absolute upward and downward IM, using

primary school completion as the educational cutoff. Focusing on the differences in upward and downward IM across denominations sheds light on the steady-state (ss) differences in

educational achievement across religious groups. We can express the evolution of the share of completed primary education for birth cohort _b_ + 1, of a religious group _g_, _ϕ__g,b_+1, as a

function of the share of those with completed primary education in the previous birth cohort, _ϕ__g,b_, and the rates of upward IM, _u__g,b_, and downward IM, _d__g,b_.

$$\begin{array}{c}{\phi }_{g,b+1}={\phi }_{g,b}(1-{d}_{g,b})+(1-{\phi }_{g,b}){u}_{g,b}\;\iff \;\varDelta {\phi }_{g,b+1}\\ \,\,=\;{u}_{g,b}-{\phi }_{g,b}({u}_{g,b}+{d}_{g,b})\iff {\phi

}_{g,{\rm{ss}}}=\frac{{u}_{g,b}}{{u}_{g,b}+{d}_{g,b}}.\end{array}$$ COHABITATION We need to observe children’s and parental education to build IM statistics. To maximize coverage, we use the

average attainment of individuals one generation older than the child in the household. (The results are similar when we take the minimum or maximum or only the father’s or mother’s

education). Matching young individuals to cohabiting older generation members raises concerns, as the transmission of education may differ for children living with and without older family

member(s) and across religions. We focus on individuals aged 14–18 years, as primary education is mostly complete by then and cohabitation rates are high57. Supplementary Information,

section B2 gives details. Cohabitation rates with older generation relatives, mainly biological parents and sometimes uncles and aunts, hover between 82% and 91%, without much difference

between Christians, Muslims and Traditionalists. RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION ACROSS GENERATIONS We explore the transmission of religious affiliation from parents to 14–18 year-old children. On the

one hand, there is high intergenerational inertia for both Muslims and Christians. The likelihood that children of Muslim or Christian parents will report a different creed is, on average,

less than 3%; in most countries, it is less than 1%. These estimates are close to the ones reported by ref. 60 across 19 African countries. On the other hand, it is common for African

Muslims and Christians to follow traditional religious rituals and ceremonies15. However, the Census does not record ‘mixed/dual’ religious affiliation. To the extent that educated Africans

adhering to Traditional religions alongside Christianity or Islam will respond that they are Christians or Muslims, the upward IM estimates for Traditionalists will be underestimated.

Supplementary Information, section B3 gives details and graphical illustrations of the conversion dynamics across denominations and discusses their implications for our patterns. ETHNICITY

AND RELIGION Given the voluminous research on ethnicity in Africa16,17,18, we examine the interplay between religion and ethnicity by tabulating censuses in which both are recorded. Religion

transcends ethnicity (Supplementary Information, section B4). Although a few ethnicities are monoreligious (for example, Wolof and Fula in Senegal and the Somali in Ethiopia are Muslim and

the Agew in Ethiopia and the Acholi in Uganda are Christian), most ethnicities, large and small, are multireligious. For example, the Oromo in Ethiopia, the Yoruba in Nigeria and the Sena in

Mozambique are split between Christianity and Islam, whereas many groups in West Africa are split between Christianity and Traditional religions. There are dozens of ethnicities split

between Traditional religions, Islam and Christianity, like the Gurma, the Basari and the Goulmancema in West Africa. Supplementary Figure D3 reports the religious IM gaps leveraging both

cross-ethnicity and within-ethnicity variation (across individuals for whom IPUMS records ethnicity). (See also Supplementary Information, section D2.2). EXPLAINING RELIGIOUS EDUCATIONAL IM

GAPS METHODOLOGY To arrive at the Christian–Muslim and the Christian–Animist gaps in upward IM and downward IM in Fig. 2, we estimate the following regression with OLS:

$${{\rm{I}}{\rm{M}}}_{ibchdt}^{{\rm{rel}}}={\alpha }_{cb}+{\gamma }_{m}{\rm{Muslim}}+{\gamma }_{a}{\rm{Animist}}+{\delta }_{h}{{\bf{H}}}_{h}^{{\prime} }+{\theta }_{h}{{\bf{I}}}_{h}^{{\prime}

}+\psi {{\bf{E}}}_{e,r,b-1}^{{\prime} }+{\phi }_{d,u/r}+{{\epsilon }}_{ibchdt}.$$ The dependent variable denotes upward or downward IM for child _i_ of religious affiliation rel, born in

decade _b_, in household _h_, residing in district _d_ in country _c_, recorded in census _t_. ‘Muslim’ is an indicator for adherents to Islam; ‘Animist’ identifies children of

Traditionalists. \({{\bf{H}}}_{h}^{{\prime} }\) is a vector of household features, including size, composition and family organization. \({{\bf{I}}}_{h}^{{\prime} }\) reflects occupation and

industry indicators for the older generation in the household. \({{\bf{E}}}_{e\,,r\,,b-1}^{{\prime} }\) denotes the share of the older generation with completed primary education in the

district for each religious group. \({{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}_{d,u/r}\) is a vector of district-specific constants interacted with an urban indicator. Parameters _γ__m_ and _γ__a_ reflect the

educational gap of Muslims and Traditionalists vis-a-vis Christians, the omitted category. CHILDHOOD REGIONAL EXPOSURE EFFECTS METHODOLOGY To isolate regional childhood exposure effects from

spatial sorting, we use an approach37 that exploits differences in the timing of children’s moves across districts with different levels of upward IM, adjusting it to derive

religion-specific exposure38. The regional childhood exposure effects, reported in Fig. 3, are estimated from the following OLS specification:

$$\begin{array}{c}{\text{IM\_up}}_{ihbmcod}^{{\rm{rel}}}={\alpha }_{ob}+{\alpha }_{m}+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{m=1}^{18}{{\rm{\beta }}}_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}\times I({m}_{i}=m)\times \,{\varDelta

}_{odb}^{{\rm{nm}}}\\ \,\,\,+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{b={b}_{0}}^{B}{k}_{b}\times I({b}_{i}=b)\times {\varDelta }_{odb}^{{\rm{nm}}}+{{\epsilon }}_{ihbmcod}\end{array}$$ The specification

relates primary education completion for child _i_, from household _h_, of birth cohort _b_, whose parents have not completed primary school, who moved from birthplace district _o_ in

country _c_ to destination district _d_ at age _m_ in the same country, to differences in upward IM between origin and destination, among non-movers of the same cohort \(b({\varDelta

}_{{odb}}=\overline{{\rm{IM}}}{\text{\_up}}_{{bd}}^{nm}-\overline{{\rm{IM}}}{\text{\_up}}_{{bo}}^{nm}\,)\). \(\overline{{\rm{IM}}}\_{{\rm{up}}}_{b}^{{\rm{nm}}}\) summarizes the economic,

social and institutional environment which shapes educational mobility in a district. We construct an overall measure of origin–destination differences in upward IM (\({\varDelta

}_{odb}^{{\rm{all}}}\)) and a religion-specific one (\({\varDelta }_{odb}^{{\rm{rel}}}\)). Origin-region × birth-decade fixed effects, _α__ob_, account for unobserved factors of the child’s

cohort and birthplace. The specification also includes interactions of destination–origin cohort IM differences with cohort effects to account for potential differential measurement error

across cohorts (this has no effect). The parameters of interest, \({\beta }_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}\), capture how children’s attainment varies with the age of their move to districts with higher

or lower upward IM, conditional on age-of-move constants, _α__m_, which absorb disruption and other age-specific features affecting education. If regions matter for mobility, the earlier the

move, the greater the impact. As we include origin cohort specific constants, we leverage variation among children born in the same district and decade, moving to regions with different

educational mobility. Differences in the age-of-move slopes, \({\gamma }_{m}={\beta }_{m}^{{\rm{rel}}}-{\beta }_{m+1}^{{\rm{rel}}}\), reflect the impact of an extra year in the high-mobility

district, regional childhood exposure effects. SAMPLE For the implementation of the movers’ design in the section on Sorting and childhood regional exposure (Fig. 3) that teases apart

childhood exposure regional effects from spatial sorting, we need data not only on the district of birth and residence but also on the length of stay in the current location. IPUMS provides

such information for 13 countries (Supplementary Table B1). The 13 countries come from all African regions. (1) Southern Africa: we have data from three (out of five) countries in the

southern part of the continent, South Africa, Zambia and Malawi, missing Mozambique and Botswana. (2) Western Africa: the childhood exposure effects are estimated using data from six (out of

ten) West African countries, Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Togo, Mali and Cameroon. (3) East Africa: we have all countries from Eastern Africa (Uganda, Rwanda and Ethiopia) except Mauritius. (4)

North Africa: the mover’s design includes Egypt, the only North African country. The 13-country sample includes French and British colonies and covers relatively poor (with meagre education)

nations and more advanced economies. REGIONAL CORRELATES OF INTERRELIGIOUS EDUCATIONAL MOBILITY DIFFERENCES RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCES IN RESIDENCE We explore differences in residence attributes

among adherents of the three main religions, running country–birth cohort fixed-effects regressions associating geographic/location, at-independence development and historical features to

indicator variables for Muslims and Traditionalists, respectively, with Christians serving as the omitted category. The specification reads: $$\begin{array}{l}{Y}_{i,c,b,r}={\alpha

}_{c,b}+{\psi }_{1}{{\rm{Muslim}}}_{i,c,b,r}+{\psi }_{2}{{\rm{Traditional}}}_{i,c,b,r}+{\zeta }_{i,r,c,b}.\end{array}$$ Extended Data Figure 3 reports population-weighted least-squares

estimates that reflect average differences in the respective outcomes, _Y__i,c,b,r_, between Christians and Muslims and Christian and Traditionalists partialling out country cohort

constants, _α__c,b_. Our exploration relates to research on the spread of Christianity and Islam in Africa. The following patterns emerge when we compare residence attributes between Muslims

and Christians: (1) Muslims reside in less developed and densely populated regions, are more reliant on agriculture and are somewhat less urbanized; (2) Muslims reside in regions away from

the capitals and the coastline, in line with works showing that missionaries mostly settled along the coast; and (3) Muslims reside in districts further away from colonial roads and

railroads and far from Protestant and Catholic missions. Turning to Animists, the tabulations show the following: (1) similar to Muslims, Africans adhering to Traditional religions reside in

less densely, more rural, agriculture-oriented regions; (2) adherents of Traditional religions reside in districts even further away from the capitals than Muslims; (3) Animists are more

likely to settle in malaria-prevalent districts; and (4) Traditionalists are found in districts far from the colonial infrastructure. SPECIFICATION OF REGIONAL CORRELATES OF RELIGIOUS IM GAP

The specification on the correlates of regional differences in upward IM between Christians and Muslims and Christians and Traditionalists reads:

$$\begin{array}{c}\mathop{{\overline{{\rm{IM}}}}_{r,c,b}^{{\rm{C}}}}\limits^{}-\mathop{{\overline{{\rm{IM}}}}_{r,c,b}^{{\rm{M,T}}}}\limits^{}={\gamma }_{{\rm{c}}}+{\phi }_{1}{D}_{r,c}+{\phi

}_{2}{G}_{r,c}+{\phi }_{3}{H}_{r,c}+{\phi }_{4}{R}_{r,c}+\lambda {E}_{r,c}^{{\rm{old}}}+{{\epsilon }}_{r,c,b}.\end{array}$$ The dependent variable is the difference in upward IM between

Christians and Muslims and between Christians and Traditionalists born in decade (birth cohort) _b_, in region _r_, in country _c_. (Hats denote regional averages across birth cohort

regions). The explanatory variables are regional proxies of early (at independence) development (_D_), geography-location (_G_), historical aspects (_H_) and religious composition (_R_),

which we include one by one in the empirical model as our objective is to characterize regional religious IM differences (rather than identify causal effects). As the specifications include

country constants (_γ_c), the coefficients capture the within-country correlation. SPECIFICATION OF REGIONAL CORRELATES OF IM, BY RELIGION We also estimate the regional specifications

separately for Muslims, Christians and adherents of Traditional religions and compared the coefficient estimates of the location, early development and historical and compositional

statistics. Extended Data Figure 4 reports the regional correlates of mobility separately for adherents of each religious group. Extended Data Figure 5 reports otherwise similar

specifications, also controlling for the share of the older generation with completed primary education in the district that is the strongest correlate of educational mobility. REPORTING

SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY All newly built statistics on faith-specific

absolute upward and downward educational IM by country, region and sex are based on census data compiled, processed and harmonized by IPUMS. IPUMS International microdata are publicly

available free of charge. To access them, the prospective user may submit an electronic authorization form providing name, electronic address and institutional affiliation here:

https://international.ipums.org/international/. Because our analyses are based on secondary, de-identified, publicly available data, we do not have an IRB waiver. CODE AVAILABILITY The code

used to construct and analyse the data was written in R v.4.2.2 and Python v.3.11. The replication code and data files are available on https://github.com/imreligionafrica/imreligionafrica

CHANGE HISTORY * _ 12 DECEMBER 2023 A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06886-9 _ REFERENCES * Nkrumah, K. _Consciencism_ (Monthly Review Press,

1964). * Nyerere, J. K. _Freedom and Development_ (Oxford Univ. Press, 1973). * _World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise_ (World Bank, 2018). * Wodon, Q.,

Male, C., Montenegro, C., Nguyen, H. & Onagoruwa, A. _Educating Girls and Ending Child Marriage: A Priority for Africa_ (World Bank, 2018). * Psacharopoulos, G. & Patrinos, H.

Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. _Edu. Econ._ 26, 445–458 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Montenegro, C. E. & Patrinos, H. A.

_Comparable Estimates of Returns to Schooling Around the World_ (World Bank, 2014). * _Religion and Education Around the World_ (Pew Research Center, 2016). * Nathan, N. Religious conversion

in colonial Africa. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 100, 147–152 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Jedwab, R., Meier Zu Selhausen, F. & Moradi, A. _The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence

from Africa and Implications for Development_ (Univ. of Oxford, 2018). * Julia, C. & Valeria, R. The long-term effects of the printing press in sub-Saharan Africa. _Am. Econ. J. Appl.

Econ._ 8, 69–99 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Majgaard, K. & Mingat, A. _Education in Sub-Saharan Countries: A Comparative Analysis_ (World Bank, 2011). * Abernerthy, D. B. _The

Political Dilemma of Popular Education: An African Case_ (Stanford Univ. Press, 1969). * Fafunwa, B. A. _History of Education in Nigeria_ (Routledge, 1964). * Laitin, D. D. _Hegemony and

Culture: Politics and Religious Change among the Yoruba_ (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1986). * Peel, J. D. Y. _Aladura_: _A Religious Movement Among the Yoruba_ (Oxford Univ. Press, 1968). *

Posner, D. N. _Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa_ (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005). * Bates, R. H. _Markets and States in Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policies_

(Univ. of California Press, 2005). * Christensen, D. & Laitin, D. D. _African States Since Independence: Order, Development, and Democracy_ (Yale Univ. Press, 2019). * Guiso, L.,

Sapienza, P. & Zingales, L. People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes. _J. Monet. Econ._ 50, 228–282 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Becker, S. O., Rubin, J. & Woessmann, L.

in _The Handbook of Historical Economics_ (eds Bisin, A. & Federico, G.) 585–639 (Elsevier, 2021). * Kuran, T. Islam and economic performance: historical and contemporary links. _J.

Econ. Lit._ 56, 1292–1359 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Manglos-Weber, N. D. Identity, inequality, and legitimacy: religious differences in primary school completion in sub-Saharan

Africa. _J. Sci. Study Relig._ 56, 302–322 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Platas, M. R. _The Religious Roots of Inequality in Africa_. PhD thesis, Stanford Univ. (2016). * Platas, M. R.

_Culture and the Persistence of Educational Inequality: Lessons from the Muslim–Christian Education Gap in Africa_ (New York Univ., 2018). * Evans, D. K. & Acosta, A. M. Education in

Africa: what are we learning? _J. African Econ._ 30, 13–54 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Narayan, A. et al. _Fair Progress?:_ _Economic Mobility Across Generations Around the World_

(World Bank, 2018). * Hertz, T. in _Unequal Chances: Family Background and Economic Success_ (eds Bowles, S. et al.) 165–191 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005). * Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline,

P. & Saez, E. Where Is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. _Q. J. Econ._ 129, 1553–1623 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Geng, Y.

_Intergenerational Mobility in China across Space and Time_ (Univ. Pompeu Fabra, 2018). * Alesina, A., Hohmann, S., Michalopoulos, S. & Papaioannou, E. Intergenerational mobility in

Africa. _Econometrica_ https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA17018 (2021). * Wantchekon, L., Klasnja, M. & Novta, N. Education and human capital externalities: evidence from colonial Benin. _Q. J.

Econ._ 130, 703–757 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Carillo, B., Charris, C. & Iglesias, W. Moved to poverty? A legacy of apartheid in South Africa. _Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ._ (in

the press). * Asher, S., Novosad, P. & Rafkin, C. _Intergenerational Mobility in India: Estimates From New Methods and Administrative Data_ (World Bank, 2018). * Michalopoulos, S.,

Naghavi, A. & Prarolo, G. Trade and geography in the spread of Islam. _Econ. J._ 128, 3210–3241 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Alesina, A. & Zhuravskaya, E. Segregation and the

quality of government in a cross section of countries. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 101, 1872–1911 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Asher, S., Novosad, P. & Rafkin, C. _Intergenerational Mobility

in India: New Methods and Estimates Across Time, Space, and Communities_ (2020); http://paulnovosad.com/pdf/anr-india-mobility.pdf. * Chetty, R. & Hendren, N. The impacts of

neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: childhood exposure effects. _Q. J. Econ._ 133, 1107–1162 (2018). Article MATH Google Scholar * Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R. &

Porter, S. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: an intergenerational perspective. _Q. J. Econ._ 135, 711–783 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Finkelstein, A., Gentzkow, M.

& Williams, H. Place-based drivers of mortality: evidence from migration. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 111, 2697–2735 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Walter, T. F.

_Misallocation of State Capacity? Evidence from Two Million Primary Schools_. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science (2020). * Michalopoulos, S. & Papaioannou, E.

Historical legacies and African development. _J. Econ. Lit._ 58, 53–128 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Cutler, D. M. & Glaeser, E. L. Are ghettos good or bad? _Q. J. Econ._ 112,

827–872 (1997). Article Google Scholar * Cutler, D. M., Glaeser, E. L. & Vigdor, J. L. When are ghettos bad? Lessons from immigrant segregation in the United States. _J. Urban Econ._

63, 759–774 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Bauer, V., Platas, M. R. & Weinstein, J. The historical legacies of Islamic rule in Africa: colonial responses and contemporary

development. _World Dev._ 152, 105750 (2022). * Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. A. _Culture, Institutions and Social Equilibria: A Framework_ (NBER, 2021); https://www.nber.org/papers/w28832

* Bisin, A. & Verdier, T. _On the Joint Evolution of Culture and Institutions_ (NBER, 2017); https://www.nber.org/papers/w23375 * Munshi, K. & Rosenzweig, M. Networks and

misallocation: insurance, migration, and the rural–urban wage gap. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 106, 46–98 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Singh, A. Learning more with every year: school year

productivity and international learning divergence. _J. Euro. Econ. Assoc._ 18, 1770–1813 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Sandefur, J. Internationally comparable mathematics scores for

fourteen African countries. _Econ. Educ. Rev._ 62, 267–286 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Jensen, R. The (perceived) returns to education and the demand for schooling. _Q. J. Econ._ 125,

515–548 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Angrist, N., Djankov, S., Goldberg, P. K. & Patrinos, H. A. Measuring human capital using global learning data. _Nature_ 592, 403–408 (2021).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Black, S. E. & Devereux, P. J. in _The Handbook of Labor Economics_ Vol. 4B (eds Card, D. & Orley Ashenfelter, O.)

1487–1541 (Elsevier, 2011). * Hertz, T. et al. The inheritance of educational inequality: international comparisons and fifty-year trends. _B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Poli._

https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.1775 (2008). * Davis, J. & Mazumder, B. _The Decline in Intergenerational Mobility After 1980_ (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 2020). * Derenoncourt,

E. Can you move to opportunity? Evidence from the great migration. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 112, 369–408 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Chetty, R. et al. Fading American dream: trends in

absolute income mobility since 1940. _Science_ 356, 398–406 (2017). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Card, D., Domnisoru. C. & Taylor, L. The intergenerational transmission

of human capital: evidence from the Golden Age of upward mobility. _J. Labor Econ._ 40, S39–S95 (2022). * Berman, Y. The long run evolution of absolute intergenerational mobility. _Am. Econ.

J._ _Appl. Econ._14, 61–83 (2022). * Deutscher, N. & Mazumder, B. Measuring intergenerational income mobility: a synthesis of approaches. _J. Econ. Lit._ _Appl. Econ._ (in the press)_._

* _Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa_ (Pew Research Center, 2010). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The paper is dedicated to A.A., who passed away

while we were revising the manuscript. We will never forget his boundless curiosity, drive and charm. We terribly miss his wit, smile and can-do attitude. We thank M. Chatzigakis for his

superb assistance with the data and codes and R. Chetty, E. Glaeser, N. Hendren and M. Poschke for their suggestions and comments. We have received helpful feedback and comments from seminar

participants at the RIDGE Conference, the NBER Summer Institute, the AEA Conference (2021), the CEPR Conference on The Economics of Religion, King’s College, Harvard, Zurich, the New

Economic School, Trinity College Dublin, the World Bank, Hebrew University and Pantheon-Sorbonne. We also thank R. Jedwab, A. Storeygard, J. Cage, V. Rueda and N. Nunn for sharing their

data. E.P. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC consolidator grant ORDINARY) and the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development at the London Business School. All

errors and omissions are our responsibility. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Economics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA Alberto Alesina * Sihlquai 10,

Adliswil, Switzerland Sebastian Hohmann * Department of Economics, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA Stelios Michalopoulos * London Business School, London, UK Elias Papaioannou Authors

* Alberto Alesina View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sebastian Hohmann View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Stelios Michalopoulos View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Elias Papaioannou View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS A.A., S.H., S.M. and E.P. were the joint principal investigators for this project. A.A. designed the study, supervised the

analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. S.H. designed the study, supervised all parts of the analysis, analysed the data and wrote and edited the paper. S.M. designed the study,

supervised all parts of the analysis, analysed the data and wrote and edited the paper. E.P. designed the study, supervised all parts of the analysis, analysed the data, wrote and edited the

paper. The study has no local authors as the analysis is based on secondary data, harmonized and made publicly available by IPUMS International. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to

Stelios Michalopoulos or Elias Papaioannou. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. PEER REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature_ thanks Sudhanshu

Handa, David Laitin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. EXTENDED DATA FIGURES AND TABLES EXTENDED DATA FIG. 1 MAJOR RELIGIONS.

21 AFRICAN COUNTRIES. The figure plots the population share of the main religions in our sample of 21 African countries. Panel (a) reports the shares across 82,037,564 individuals of all

ages. Panel (b) reports weighted shares using the countries’ populations in 1980. The Christian share combines various denominations, like Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant, available in

some censuses. Likewise, the Muslim share combines various branches, like Sunni and Shia. Traditional also combines various indigenous religions, like Vodun, Animist, and Traditional

religions. Supplementary Fig. A2 gives country-specific details. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 2 CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM IM GAP DRIVERS, BY COUNTRY. The figure portrays how the Christian–Muslim gap in

educational upward IM (panel (a)) and downward IM (panel (b)) changes as we add controls for the household structure (model (2), in green), parental occupational specialization, the industry

of employment, and rural–urban residence (model (3), in red), the share completed primary education of the older generation of the same religious group in the district (model (4), in

purple), and district x rural/urban fixed effects (model (5), in dark yellow) for each country. The last permutation (model (6), in light blue) restricts estimation in half of each country’s

districts, where differences in completed primary education of the older generation between Christians and Muslims are the smallest. The bars on the top (model (1), in dark blue) reflect

the baseline inter-religious differences in IM, conditioning on birth cohort fixed effects and age constants. The figure gives linear probability model (OLS) estimates. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 3

DISTRICT CORRELATES OF RESIDENCE BY RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION. The figure plots OLS regression coefficients associating the variable listed on the left of the graph to indicator variables for

Muslims and Traditionalists, with Christians serving as the omitted category, conditioning on country–birth cohort fixed effects. The estimates have, therefore, a within-country–birth-decade

test of means interpretation. There are three categories of independent variables. (i) Regional proxies of development before independence. (ii) Regional geographic and location features.

(iii) Historical variables of colonial investments and precolonial statehood. Supplementary Section F gives variable definitions and sources. Two-standard-error bands based on

heteroskedasticity adjusted clustered at the country level are also reported. The point estimates (green and blue dots in the figure) were obtained by running separate regressions of the

district-level Christian–Muslim and Christian - Traditional IM gap respectively on each district-level variable (indicated on the vertical axis of the figure). The IM gap is defined as the

average IM of Christians minus the average IM of Muslims or Traditionalists in the district. Before running each regression, we standardize the dependent and independent variable by

subtracting its sample mean and dividing by its sample standard deviation. EXTENDED DATA FIG. 4 REGIONAL IM CORRELATES BY RELIGION, COUNTRY FIXED EFFECTS. The figure plots correlations

(standardized “beta” coefficients) between intergenerational mobility (IM) and various regional characteristics for Christians (red star), Muslims (green rhombus), and Traditionalists (blue

square). Panel (a) examines upward IM that reflects the likelihood that young individuals, aged 14–18, residing in households where the older generation has not completed primary schooling,

will complete primary education. Panel (b) examines downward IM that reflects the likelihood that young individuals, aged 14–18, residing in households where the older generation has

completed primary schooling will fail to do so. There are four categories of IM correlates. (i) Proxies of development before independence. (ii) Location and geographic features. (iii)

Historical variables, including colonial-era investments and precolonial statehood. (iv) Homogeneity, captured by the shares of each of the three religious groups. Supplementary Section F

gives variable definitions and sources. All specifications include country fixed effects (constants not reported). Standard errors are clustered at the country level. The point estimates

(green and blue dots in the figure) were obtained by running separate regressions of the district-level Christian–Muslim and Christian - Traditional IM gap respectively on each

district-level variable (indicated on the vertical axis of the figure). The IM gap is defined as the average IM of Christians minus the average IM of Muslims or Traditionalists in the

district. Before running each regression, we standardize the dependent and independent variable by subtracting its sample mean and dividing by its sample standard deviation. EXTENDED DATA

FIG. 5 REGIONAL IM CORRELATES, COUNTRY FE, COND. ON OWN RELIGION OLD’S COMPLETED PRIMARY. The figure plots correlations (standardized “beta” coefficients) between intergenerational mobility

(IM) and various regional characteristics for Christians (red star), Muslims (green rhombus), and Traditionalists (blue square), conditioning on their own religious group older generation’s

completed primary education in the district. Panel (a) examines upward IM that reflects the likelihood that young individuals, aged 14–18, residing in households where the older generation

has not completed primary schooling, will complete primary education. Panel (b) examines downward IM that reflects the likelihood that young individuals, aged 14–18, residing in households

where the older generation has completed primary schooling will fail to do so. There are four categories of IM correlates. (i) Proxies of development before independence. (ii) Location and

geographic features. (iii) Historical variables, including colonial-era investments and precolonial statehood. (iv) Homogeneity, captured by the shares of each of the three religious groups.

Appendix Section F gives variable definitions and sources. All specifications include country fixed effects (constants not reported). Standard errors are clustered at the country level. The

point estimates (green and blue dots in the figure) were obtained by running separate regressions of the district-level Christian–Muslim and Christian–Traditionalist IM gap, respectively,

on each district-level variable (indicated on the vertical axis of the figure). The IM gap is defined as the average IM of Christians minus the average IM of Muslims or Traditionalists in

the district. Before running each regression, we standardize the dependent and independent variable by subtracting its sample mean and dividing by its sample standard deviation. EXTENDED

DATA FIG. 6 DISTRICT CORRELATES OF CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM AND CHRISTIAN–TRADITIONALIST IM GAPS, CONDITIONAL ON OLDER GENERATION’S COMPLETED PRIMARY. The figure plots correlations (standardized

“beta” coefficients) between upward IM gaps of Christians and Muslims (green circle) and Christians and Traditionalists (blue square), averaged across individuals in a district, and various

regional characteristics. (i) Proxies of development before independence. (ii) Location and geographic features. (iii) Historical variables of colonial investments and precolonial statehood.

(iv) Homogeneity, captured by the shares of each of the three religious groups. Supplementary Section F gives variable definitions and sources. All specifications include country fixed

effects (constants not reported). Two-standard-error bands based on heteroskedasticity adjusted clustered at the country level are also reported. The point estimates (green and blue dots in

the figure) were obtained by running separate regressions of the district-level Christian–Muslim and Christian–Traditionalist IM gap respectively on each district-level variable (indicated