Simvastatin therapy attenuates memory deficits that associate with brain monocyte infiltration in chronic hypercholesterolemia

Simvastatin therapy attenuates memory deficits that associate with brain monocyte infiltration in chronic hypercholesterolemia"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Evidence associates cardiovascular risk factors with unfavorable systemic and neuro-inflammation and cognitive decline in the elderly. Cardiovascular therapeutics (e.g., statins and

anti-hypertensives) possess immune-modulatory functions in parallel to their cholesterol- or blood pressure (BP)-lowering properties. How their ability to modify immune responses affects

cognitive function is unknown. Here, we examined the effect of chronic hypercholesterolemia on inflammation and memory function in Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout mice and

normocholesterolemic wild-type mice. Chronic hypercholesterolemia that was accompanied by moderate blood pressure elevations associated with apparent immune system activation characterized

by increases in circulating pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes in ApoE-/- mice. The persistent low-grade immune activation that is associated with chronic hypercholesterolemia facilitates the

infiltration of pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes into the brain of aged ApoE-/- but not wild-type mice, and links to memory dysfunction. Therapeutic cholesterol-lowering through

simvastatin reduced systemic and neuro-inflammation, and the occurrence of memory deficits in aged ApoE-/- mice with chronic hypercholesterolemia. BP-lowering therapy alone (i.e.,

hydralazine) attenuated some neuro-inflammatory signatures but not the occurrence of memory deficits. Our study suggests a link between chronic hypercholesterolemia, myeloid cell activation

and neuro-inflammation with memory impairment and encourages cholesterol-lowering therapy as safe strategy to control hypercholesterolemia-associated memory decline during ageing. SIMILAR

CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HIGH LEVELS OF 27-HYDROXYCHOLESTEROL RESULTS IN SYNAPTIC PLASTICITY ALTERATIONS IN THE HIPPOCAMPUS Article Open access 12 February 2021 AGE-LINKED SUPPRESSION

OF LIPOXIN A4 ASSOCIATES WITH COGNITIVE DEFICITS IN MICE AND HUMANS Article Open access 10 October 2022 APOE-Ε4 MODULATES THE ASSOCIATION AMONG PLASMA AΒ42/AΒ40, VASCULAR DISEASES,

NEURODEGENERATION AND COGNITIVE DECLINE IN NON-DEMENTED ELDERLY ADULTS Article Open access 29 March 2022 INTRODUCTION Cognitive decline is an increasingly common problem that progresses with

age. By gradually interfering with daily functioning and well-being, it poses an enormous burden on affected people and their environment1,2. In recent years, the apparent role of

cardiovascular risk factors as important modifiable elements in the development of cognitive decline has become the subject of clinical as well as pre-clinical research efforts2,3,4. There

exists a prominent link between mid-life chronic hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertension and the development of dementia later in life5,6. As a consequence, the management of cardiovascular

risk factors not only serves to prevent often detrimental acute consequences of hypertension or dyslipidemia, but also to minimize potential adverse cognitive outcomes later on. A number of

observational and randomized studies reported beneficial effects of antihypertensive therapies on cognitive outcome7,8,9. Nonetheless, existing distinctions regarding effectiveness between

different classes of hypertension medication have been shown7. Likewise, the use of statins in controlling risk factors for dementia prevention or treatment is controversially discussed.

Their therapeutic efficacy that initially emerged from findings showing its positive effects on various factors related to memory function10,11 was increasingly argued as case studies raised

concerns regarding a contributory role of statins in development of cognitive problems12,13. Due to the discrepancies observed between studies and the lack of knowledge regarding underlying

mechanisms, strategies to combat cognitive impairment resulting from cardiovascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease (CVD) are yet to be established. Immune system alterations and

inflammation are not only hallmarks of many CVDs and their risk factors but have increasingly been recognized as contributors to impaired cognitive function in older people14,15,16.

Pharmaceuticals directed against inflammation evidently improve cognitive alterations associated with normal aging, CVDs, and classical neurodegenerative diseases17,18. Multiple drugs

commonly used in the cardiovascular field possess immune-modulatory actions in parallel to their principal cholesterol- or blood pressure (BP)-lowering effects19,20. One of the bottlenecks

hampering the targeted use of CVD therapeutics as an approach to minimize CVD-associated cognitive impairment is the lacking understanding of specific inflammatory signatures that relate to

cognitive impairment in patients with increased cardiovascular burden. The herein presented study investigated the effect of chronic exposure to elevated plasma cholesterol levels on

systemic and neuro-inflammation, and memory function in ageing mice. Using mice deficient in Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), which normally facilitates cholesterol clearance in the liver and thus,

controls plasma cholesterol levels, allowed us to mimic a chronically hypercholesterolemic state under normal dietary conditions. To study the effect of chronic hypercholesterolemia (i.e.,

higher-than-normal plasma cholesterol already apparent at 4-months of age) on systemic and neuro-inflammation and memory performance, we compared ApoE-/- mice to normocholesterolemic

wild-type (WT) mice. We tested the efficacy of CVD therapeutics as treatment for memory impairment associated with the increased cardiovascular burden in aged ApoE-/- mice (i.e., increased

plasma cholesterol and higher-than-normal BP). To this end, we therapeutically administered the statin simvastatin that has been attributed a strong anti-inflammatory character by regulating

proliferation and activation of macrophages21,22, and/or the smooth muscle relaxant agent hydralazine, known to reduce leukocyte migration in spontaneously hypertensive rats23. Our findings

provide evidence that early life exposure to chronically high cholesterol levels (i.e., apparent at 4-months of age) rather than increases in plasma cholesterol and BP later in life

negatively affect memory performance. We underscore a role of myeloid cell activation in the development of neuro-inflammation associated with chronic hypercholesterolemia as well as cell

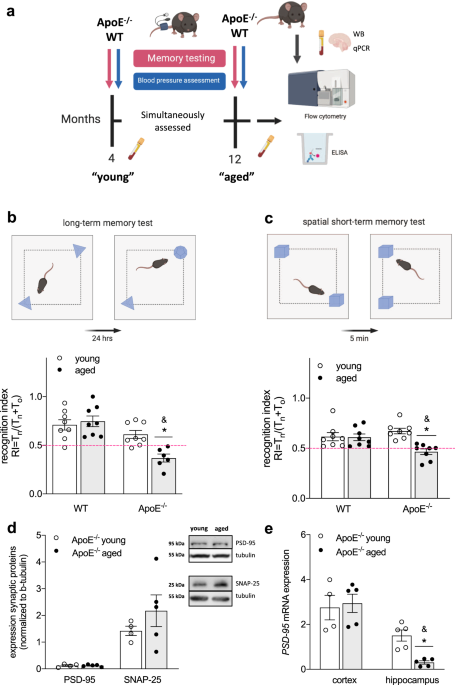

type-specific drug effects that may limit their efficacy. RESULTS CHRONIC HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA CONTRIBUTES TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEMORY IMPAIRMENT To investigate whether chronic exposure to

higher-than-normal plasma cholesterol levels affects important brain functions (i.e., cognition) during ageing, we tested memory function in normocholesterolemic WT and hypercholesterolemic

ApoE-/- mice at 4 and 12 months of age (Fig. 1a). In accordance with the increased cardiovascular burden in aged ApoE-/- compared to WT mice (i.e., chronic hypercholesterolemia as evident

from higher-than-normal plasma cholesterol already apparent at 4 months of age and higher systolic BP at 12 months of age in ApoE-/- mice; Table 1), long-term (hippocampus-dependent) memory

function deteriorated with age in ApoE-/- mice, resulting in significantly lower recognition indices (RI) compared to age-matched WT controls (RI ≤ 0.5; Fig. 1b). Although neither aged WT

nor aged ApoE-/- mice presented with signs of short-term (rhino-cortical) memory impairment when compared to their young controls (Supplementary Table 1), spatial short-term memory was

compromised in aged ApoE-/- mice as evident by a lower RI obtained in an object placement test (RI ≤ 0.5; Fig. 1c). When testing for age-related changes in pre- and post-synaptic proteins in

whole brain lysates of ApoE-/- mice, no differences in expression of synaptosomal associated protein 25 (SNAP-25) or postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) were observed (Fig. 1d). In

accordance with previous studies24, however, ageing affected hippocampal but not cortical PSD-95 mRNA expression in ApoE-/- mice (Fig. 1e). Taken together, these data imply brain

region-specific negative effects of early and chronic hypercholesterolemia on memory function later in life. PRO-INFLAMMATORY MONOCYTES INFILTRATE THE BRAIN OF AGED APOE-/- BUT NOT WT MICE

In chronically hypercholesterolemic ApoE-/- mice, ageing associated with apparent immune system activation as evident by a higher number of circulating Ly6Chi monocytes (Fig. 2a) and

elevated plasma levels of interleukin (IL)12/23 (Fig. 2b). The latter is often secreted by activated monocytes/macrophages promoting T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 priming of T cells25, which

secrete IL17 amongst other cytokines and are considered main contributors to tissue inflammation26. Elevated IL17 plasma levels in aged ApoE-/- mice (Fig. 2c) led us to test immune cell

infiltration into brain tissue. FACS analyses revealed an increase of Ly6Chi pro-inflammatory monocytes (Fig. 2d) and a higher percentage of overall T cells (positive for the pan-T-cell

marker CD3) in brain tissue of aged vs. young ApoE-/- mice (Fig. 2e). Transcripts of key chemokines that regulate migration and infiltration of monocytes and macrophages, such as monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and chemokine ligand-2 (CXCL2) were drastically elevated in whole brain tissue of the aged cohort compared to young control mice (Table 2). Moreover, an

mRNA expression pattern typical of a pro-inflammatory phenotype was predominant in whole brain tissue of aged ApoE-/- mice compared to young ApoE-/- controls (Table 2). The degree of

cytokine expression was brain region-dependent as evidenced by a markedly higher hippocampal than cortical IL12 expression in aged ApoE-/- mice compared to young controls (Table 2). IL23

also showed such region-specific expression patterns (Table 2). Besides, Arginase-1 (Arg-1) as commonly used marker for an alternatively activated macrophage phenotype presented with

region-specific expression patterns: while cortical Arg-1 mRNA levels remained unaffected by age, the basally higher hippocampal Arg-1 expression significantly reduced with age (Table 2).

Together, these data point to an apparent age-related inflammation in the hippocampus and may explain the more pronounced hippocampal-dependent memory impairment in aged ApoE-/- mice.

Although WT mice presented with an age-related increase of plasma cholesterol, BP (Table 1) and circulating Ly6Chi pro-inflammatory monocytes (Fig. 2a), the percentage of Ly6Chi monocytes

remained unaltered in the brain of aged WT mice (Fig. 2d). Notably compared to WT mice, ApoE-/- mice already showed a significantly higher proportion of circulating Ly6Chi cells at young age

(Fig. 2a), suggesting a persistent pro-inflammatory state in chronically hypercholesterolemic ApoE-/- mice, which may promote immune infiltration into the brain with implications for memory

function. Correspondingly, the proportion of brain Ly6Chi monocytes was higher in ApoE-/- mice compared to that in age-matched WT mice (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, brain tissue of aged ApoE-/-

mice presented with significantly higher transcripts levels of chemokines MCP-1 and CXCL2 compared to aged-matched WT controls (Supplementary Table 2). Taken together, these data suggest a

key role for Ly6Chi monocyte activation and brain infiltration during chronic hypercholesterolemia where memory deficits were also observed. CHOLESTEROL- AND/OR BP-LOWERING THERAPY ATTENUATE

NEURO-INFLAMMATION IN AGED APOE-/- MICE As chronically hypercholesterolemic ApoE-/- mice at 12 months of age presented with marginally elevated BP compared to 4-months-old ApoE-/- mice, we

subjected aged ApoE-/- mice (i.e., 12 months of age) to lipid-lowering or BP-lowering therapy for 8 consecutive weeks, using the statin simvastatin (0.5 mg/kg/d) or the smooth muscle

relaxant hydralazine (5 mg/kg/d). Because we did not anticipate statin-mediated effects on BP, we also administered a combination of the two drugs to a group of animals (Fig. 3a). The doses

administered correspond to therapeutic doses used in the clinic (20 mg/kg/d and 10 mg/kg/d, respectively). All treatment strategies proved similarly effective in lowering the age-related

elevated systolic BP: longitudinal BP measurements revealed markedly lower BP values in mice post treatment compared to the recorded pre-treatment values (Supplementary Fig. 1). As expected,

simvastatin treatment revealed significant cholesterol-lowering effects (Table 3). In line with other investigations27,28, simvastatin treatment markedly reduced the age-related elevated

heart-to-body weight ratio in our model without significantly affecting heart rate (Table 3). Interestingly, simvastatin’s effects on cardiac hypertrophy and cholesterol were diminished in

the presence of hydralazine (Table 3). Simvastatin revealed considerable anti-inflammatory capacity as evidenced by a reduction of circulating plasma IL12/23 levels (Fig. 3b) and IL17 levels

in vivo (Fig. 3c). In the brain, simvastatin-treated mice revealed lower transcript levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL6 and IL12, MCP-1 and CXCL2 (Table 4).

Notably, hydralazine attenuated simvastatin’s effects for some of the cytokines when administered in combination (Table 4). Treatment affected brain regions to different degrees as supported

by statistically significant differences in hippocampal but not cortical IL12 expression between simvastatin- and hydralazine-treated groups (Table 4). Interestingly, IL23 revealed a

different expression profile with significantly lower cortical IL23 expression in simvastatin-containing treatment groups while hippocampal IL23 expression only significantly changed when

mice received simvastatin alone (Table 4). CHOLESTEROL- AND/OR BP-LOWERING THERAPY AFFECT MICROGLIA PHENOTYPE IN AGED APOE-/- MICE The age-related increase of CD68 (monocyte/macrophage

activation marker) in ApoE-/- mice was significantly lower in groups treated with simvastatin (Fig. 3d). Since a majority of CD68+ cells were positive for ionized calcium-binding adapter

molecule-1 (Iba-1; common microglia/macrophage marker) we assessed how age and treatment affected the number of total and CD68+ brain macrophages, and investigated their morphology by

counting the numbers of ramified (= resting), intermediate and round (= activated) Iba-1+ cells. Ageing associated with increased numbers of CD68 + Iba-1+ cells in two hippocampus regions

that are linked to spontaneous retrieval of episodic contexts and context-dependent retrieval of information, formation of new episodic memories, and spontaneous exploration of novel

environments (i.e., Cornu Ammonis (CA) 1 and Dentate Gyrus (DG), respectively) but not in the cortex of ApoE-/- mice (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 2a), indicative of region-specific

augmentation of macrophage activation. Both hydralazine- and simvastatin-treated mice presented with lower numbers of CD68 + Iba-1+ cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 3e); yet,

only simvastatin revealed similar responses in the DG (Fig. 3f). Neither drug affected CD68 + Iba-1+ cell counts in the cortex (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The total number of Iba-1+ cells

significantly increased with age in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 3g) but not in DG or cortex (Supplementary Fig. 2b/c), suggesting region-specific proliferation of resident

macrophages or accumulation of monocyte-derived macrophages. Yet, significant age-related changes in Iba-1+ cell morphology were only observed in the hippocampal DG region as evidenced by a

reduced proportion of ramified and increased amount of intermediate microglia (Table 5), adding to the notion that age elicits brain region-specific responses in chronically

hypercholesterolemic mice. Treatment differently affected overall Iba-1+ cell number and morphology. While hydralazine treatment showed no apparent effects in any of the investigated brain

regions (Table 5), mice treated with simvastatin presented with a markedly lower overall count of Iba-1+ cells (Fig. 3g) and significantly reduced percentage of ramified and increased

quantity of intermediate Iba-1+ cells compared to aged ApoE-/- mice in the hippocampal CA1 region and in the cortex (Table 5). Interestingly, simvastatin-treated mice presented with overall

lower numbers of Iba-1+ cells compared to young ApoE-/- in both hippocampal DG and cortex (Supplementary Fig. 2) and marked changes in Iba-1+ cell morphology in all brain regions (Table 5).

Similarly, combination treatment significantly reduced the number of ramified cells compared to young ApoE-/- mice in all brain regions investigated but markedly increased the proportion of

activated cells compared to aged ApoE-/- in the hippocampal brain region without affecting overall Iba-1+ cell counts (Table 5). Macrophages are highly plastic and adopt a variety of

phenotypes on the scale between classically activated and alternatively activated phenotypes in response to various stimuli29. Simvastatin treatment attenuated the expression of several

markers, characteristic for classical activation (i.e., tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL6, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS); Table 3) and significantly mitigated CD86 expression

(Fig. 3h) that has been shown to involve in pro-inflammatory phenotype-mediated retinal degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)30,31. Of markers typical for alternatively activated

macrophages, only Arg-1 was detected in cortical and hippocampal brain tissue in our model. Arg-1 mRNA expression significantly reduced with age in ApoE-/- mice, but aged mice treated with

simvastatin presented with higher hippocampal Arg-1 mRNA expression (Table 4). Together, these data are suggestive of brain region-specific macrophage activation during ageing in ApoE-/-

mice and an alternatively activated phenotype predominance after simvastatin treatment. Lastly, the age-related accumulation of CD3 was diminished in all treatment groups (Fig. 3i). Using

Western blotting, CD3 was not detected in brain tissue of young ApoE mice. This experimental group is therefore not shown in Fig. 3I. CHOLESTEROL- AND/OR BP-LOWERING THERAPY ATTENUATE MEMORY

DEFICITS IN AGED APOE-/- MICE In an open field test, only simvastatin treatment significantly improved age-related impaired mobility in ApoE-/- mice (Fig. 4a). Combination treatment with

hydralazine revealed no apparent effects on mobility; yet, statistical analysis disclosed no difference to young control. Likewise, hippocampal-dependent memory function (Fig. 4b) and

spatial short-term memory function (Fig. 4c) significantly improved in all treatment groups containing simvastatin. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), an important regulator of white

matter integrity, hippocampal long-term potentiation and consequently, learning and memory32, was negatively affected by age in ApoE-/- mice, and only simvastatin treatment mitigated the

age-related reduction of hippocampal BDNF expression (Fig. 4d). Similarly, immune staining of hippocampal BDNF and the neuronal marker NeuN revealed evident differences between young and

aged mice (Supplementary Table 3, representative images shown in Fig. 4e). When normalized to the number of NeuN+ cells, BDNF expression was significantly lower in aged brains compared to

young ApoE-/- mice, and only significantly higher after treatment with simvastatin alone (Fig. 4e). NeuN immunostaining, however, was significantly higher in all treatment groups that

received simvastatin compared to untreated aged ApoE-/- mice (Supplementary Table 3). Similar to the hippocampus, immune staining for BDNF in the cortex revealed significant differences

between young and aged ApoE-/- mice, but all treatment regimens presented with high BDNF protein expression in this brain region (Supplementary Table 3). Most notably, however, NeuN immune

staining only significantly differed in hippocampus but not cortex where neither age nor treatment affected NeuN expression (Supplementary Table 3), further supporting a prominent

hippocampus-dependent memory impairment in aged chronically hypercholesterolemic ApoE-/- mice. SIMVASTATIN AND HYDRALAZINE EXERT CELL-SPECIFIC EFFECTS The observed differences of simvastatin

and hydralazine treatment on inflammatory responses in vivo, led us to evaluate their effects in vitro using different immune cell subtypes of human origin. Utilizing a human monocytic

cell-line (THP-1) allowed us to assess drug effects not only in monocytes but also in monocyte-derived macrophages after differentiation. Flow cytometric analyses of monocytic or phorbol

12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-differentiated THP-1 cells revealed a strong pro-inflammatory effect of hydralazine in monocytic cells (i.e., augmentation of Lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-associated CD14 + CD16 + surface expression; 2.5-fold; Fig. 5a) compared to PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells where hydralazine did not increase CD14 + CD16 + surface expression (Fig.

5b). Similar cell type-specific effects were observed for the surface expression of the activation marker CD69 that significantly increased with hydralazine but not simvastatin treatment in

monocytic THP-1 cells but not in PMA-differentiated macrophages (Supplementary Table 4). Pro-inflammatory cytokine profiling in THP-1 cells revealed that LPS-induced augmentation of

intracellular IL6 protein abundance was not affected by simvastatin treatment but exacerbated in the presence of hydralazine (Fig. 5c). Hydralazine alone (without LPS pre-stimulation)

disclosed similar pro-inflammatory effects (Fig. 5d). Different from monocytic cells, LPS-induced IL6 expression was similarly reduced in the presence of simvastatin or hydralazine in

PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells (Fig. 5e), indicative of cell type-specific drug responses. Similarly, LPS-induced augmentation of TNF-α mRNA expression only reversed in

simvastatin-containing treatment groups but not with hydralazine in monocytic THP-1 cells (Fig. 5c). In support of this, LPS-induced elevation of TNF-α and IL6 secretion in murine

bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) reduced with both simvastatin and hydralazine treatment (Fig. 5g, h). Moreover, we detected lower surface expression of activation markers (i.e.,

CD86, CD80) in BMDMs of all treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Lastly, we used primary human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages to confirm cell type-specific drug effects:

hydralazine significantly induced cell activation (i.e., increased CD69 expression) that affected monocytes with a higher magnitude than macrophages (Fig. 5i, Supplementary Table 4) while

simvastatin presented with no appreciable effects on CD69 expression (Fig. 5j, Supplementary Table 4). Similar to CD69, hydralazine increased monocyte and macrophage CD3 expression in both

primary human cells and THP-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a–e, Supplementary Table 4), which has been shown to involve in the delivery of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α) by

macrophages.33 Notably, none of the drugs showed effects on T-cell activation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, these data suggest cell type-specific drug effects that may benefit

simvastatin as it exerted anti-inflammatory effects in both activated monocytic cells and activated macrophages. Hydralazine on the other hand, induced pro-inflammatory signatures especially

in monocytic cells with potential implications for conditions characterized by elevated monocyte counts like chronic hypercholesterolemia, which may explain some of the effects we observe

in vivo. DISCUSSION The present study provides compelling evidence that chronic hypercholesterolemia majorly contributes to the development of memory impairment, involving pro-inflammatory

processes. The herein established link between chronically elevated plasma cholesterol and the development of memory impairment in aged mice is based on findings, showing that only early

exposure to elevated plasma cholesterol (i.e., as evident in ApoE-/- mice already at 4 months of age), indicative of chronic hypercholesterolemia, results in reduced long-term and spatial

memory function at an older age (i.e., 12 months of age). This conclusion aligns with data obtained in epidemiological studies supporting a correlation between early- or mid-life cholesterol

levels to dementia later in life34,35. Similar to our findings obtained in aged normocholesterolemic WT mice, no association between cognitive function and cholesterol levels was found in

studies testing older patients36,37. Interestingly, it has been shown that female ApoE-/- mice display greater cognitive impairment than male ApoE-/- mice38,39. The fact that female ApoE-/-

mice develop more severe atherosclerosis and vascular impairment earlier40 supports the hypothesis that atherosclerosis contributes to cognitive dysfunction in this model. This is further

signified by findings showing an absence of cognitive deficits in female brain-specific ApoE-/- mice that are characterized by absence of systemic hypercholesterolemia39. Thus, further

investigations of sex-specific hypercholesterolemia effects on systemic and neuro-inflammation are needed. Although hypercholesterolemia was generally accompanied by higher-than-normal BP in

aged ApoE-/- mice, cholesterol-lowering rather than BP-lowering therapy significantly improved the impaired spatial memory of aged ApoE-/- mice. This further positions early life exposure

to high cholesterol levels as major contributor to cognitive dysfunction in addition to potential BP-mediated structural and functional alterations in the brain3. Unlike statins for

dyslipidemia treatment, hydralazine is not the first line medication for treating elevated BP. Nonetheless, hydralazine appears as first choice of BP-lowering therapy in numerous

experimental studies3,41,42, and is often used in the clinic to treat preeclampsia. Besides its vasorelaxant properties, it is thought to exert effects on the immune system, specifically on

T-cell transmigration23 and apoptosis43. However, hydralazine-induced increases of cellular CD3-zeta chain content in T cells are discussed to facilitate excessive drug-induced

auto-immunity44. The pronounced enhancement of monocytic cell activation we observed in the presence of hydralazine might be resultant from reactive metabolites deriving from hydralazine

oxidation45 or from hydralazine-mediated inhibition of DNA methyltransferase46, which are postulated as major mechanisms in drug-induced auto-immunity, might limit its potency to resolve

neuro-inflammatory processes and to improve memory deficits in our model. Moreover, it might limit therapeutic efficacy of other drugs when administered in combination. This effect calls for

the need to test for potential interactions between BP-lowering drugs of different nature and statins for potential consequences on immune regulation and cognitive impairment. It will be of

utmost importance to further investigate the value of different classes of BP-lowering drugs in multi-morbid systems. The activation of the immune system emerged as an important driver in

the aged and vulnerable brain. Experimental studies verified the significance of inflammation in CVD progression47,48 and showed that inflammation associated with cardiovascular risk factors

or CVD negatively affects cognitive function17,18,49,50. However, precise pro-inflammatory mechanisms contributing to accelerated cognitive decline and dementia risk require further

elucidation. Similar to a study that links the Th17 - IL17 pathway to high dietary salt-induced cognitive impairment in mice50, we observe elevated IL17 plasma levels in cognitively impaired

aged ApoE-/- mice with elevated cholesterol and BP levels. Further, the link between circulating IL17 levels and memory performance is strengthened as simvastatin-mediated lowering of

plasma cholesterol, BP and IL17 levels improved memory function. Another experimental study convincingly associates high fat diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in aged ApoE-/- mice not only

with elevated plasma levels of IL6, TNF-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ but also higher transcript levels of pro-inflammatory chemokine MCP-1 in brain tissue of these mice51. In our study, we

witness a similar increase of such key chemokines responsible for regulating migration and infiltration of monocytes in brain tissue of standard chow-fed aged ApoE-/- but not aged-matched WT

mice. Consequently, the accumulation of pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes in the brain was absent in aged WT mice where plasma cholesterol levels only increase later in life and thus,

positions pro-inflammatory monocytes as important contributors to neuro-inflammation emanating from chronic hypercholesterolemia. The concept of hypercholesterolemia-associated

neuro-inflammation was recently investigated in aged hypercholesterolemic ApoE-/- mice where choroid plexus lipid accumulation induced leukocyte infiltration that extended to the adjacent

brain parenchyma, demonstrating that lipid-triggered complement cascade activation promotes leukocyte infiltration into the choroid plexus with implications for immune system activation,

cognitive decline in late onset AD and atherosclerotic plaque formation52. Together with the finding that brain-specific ApoE deficiency protects from cognitive decline in the absence of

hypercholesterolemia39, this further signifies the importance of chronic hypercholesterolemia in neuro-inflammatory and -degenerative processes observed in our model. The herein

characterized brain region-specific neuro-inflammation (i.e., brain macrophage proliferation and activation, cytokine and classical/alternative microglia activation marker expression)

together with distinct brain region-specific changes after cholesterol-lowering therapy, however, also suggest additional simvastatin-mediated mechanisms independent of cholesterol-lowering.

Our experimental strategy demonstrates that simvastatin therapy proves effective in reducing neuro-inflammation associated with chronic hypercholesterolemia in aged ApoE-/- mice. In

particular, its beneficial hippocampal-specific effects on Iba-1+ cell number and morphology, CD86 and Arg-1 expression in our model point towards additional therapeutic mechanisms

independent of cholesterol-lowering. Simvastatin’s anti-inflammatory character might be resultant from its potency to regulating proliferation and activation of monocytes and

macrophages19,21, and to modulating myeloid cell phenotype53 and secretory function54,55. The presented in vitro findings describe simvastatin’s direct therapeutic effect on monocyte and

macrophage activation and extent previous reports that showed an effective reduction of cytokine secretion in PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells pre-treated with simvastatin54. In its role as

modulator for IL secretion from monocytes and macrophages, simvastatin was shown to indirectly inhibit IL17 secretion from CD4+ T cells56. Moreover, simvastatin has been shown to directly

inhibit the expression of a transcription factor responsible for controlling IL17 production in CD4+ T cells56. These findings support our herein presented data showing a reduction of IL17

plasma levels in vivo only after simvastatin treatment. However, it remains to be determined whether the simvastatin effects in our model are mediated through direct modulation of Th17

responses, indirectly through modulation of myeloid cell activation or primarily through its lipid-lowering capacity. Because simvastatin has also been associated with Th2 immune response

and neuronal recovery57,58 we cannot exclude a potential therapeutic effect on T cells in our model. Nonetheless, our results point to therapeutic effects through monocyte modulation, which

aligns with studies conducted in patients at high risk for vascular events where a simvastatin-induced downregulation of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor on monocytes but not T cells

significantly affected angiotensin II activity and thus, contributes to its anti-inflammatory profile and therapeutic effects in CVD59. Moreover, in patients with hypercholesterolemia,

simvastatin was shown to reduce monocyte secretory function55,60. Most interestingly in respect to neurodegeneration is a study reporting a lowering of the CD14 + CD16 + “intermediate”

monocyte subset in purified monocytes isolated from peripheral blood of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients in response to an ex vivo treatment with simvastatin, as this particular

subset of monocytes is closely linked to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders53. In contrast to case reports discussing adverse effects of statins on cognitive function12,13, our study

describes favorable outcomes for memory function in aged ApoE-/- mice after statin therapy, supporting findings from two large randomized control trials on simvastatin61 and pravastatin62

where no link between statin use and cognitive decline was observed. Although lipophilic statins, such as simvastatin are thought to cross the blood–brain barrier, leading to a reduction of

cholesterol availability and thereby, disturbing the integrity of the neuronal and glial cell membrane63, simvastatin treatment had no negative effects on hippocampal neurons, and

significantly increased hippocampal and cortical BDNF expression in our model. Most beneficial effects of simvastatin in the brain are thought to root from the promotion of hippocampal

neurogenesis, the inhibition of mesangial cell apoptosis64,65, the enhancement of neurotrophic factors, and the restriction of inflammation66. In light of this, simvastatin treatment

markedly increased hippocampal expression of BDNF, which has been linked to improved functional recovery after stroke and the amelioration of depressive-like behavior67,68, and may underlie

the improvements in hippocampal-dependent memory function we observe in our model. Besides, preventative simvastatin treatment resulted in lower Aβ 40/42 levels in cerebrospinal fluid of AD

mice, attenuated neuronal apoptosis, and improved cognitive competence of the hippocampal network69, suggesting that statin treatment may prevent the age-related, progressive neuropathy

characteristic for 3xTg-AD mice. Further investigation of Amyloid β accumulation in respect to neuro-inflammation and its modifiability by cholesterol-lowering or anti-inflammatory therapies

would certainly elevate the impact of statin therapy beyond the field of CVD and associated target organ damage. Taken together, our study convincingly links chronic hypercholesterolemia to

myeloid cell activation, neuro-inflammation, and memory impairment, supporting the notion that early rather than late-life exposure to cardiovascular risk factors promotes the development

of cognitive dysfunction. Cholesterol-lowering therapy provides effectiveness to improving memory function potentially by reducing monocyte-driven inflammatory events and hence, emerges as

safe therapeutic strategy to control CVD-induced memory impairment and represents another benefit of statins in patients with hypercholesterolemia. STUDY LIMITATIONS AND OUTLOOK

Controversies regarding BP phenotype in ApoE-/- mice persist; however, it is difficult to draw conclusions from the current literature as studies differ in duration, diet, and animal age.

Dinh and colleagues reported a lack of BP elevation in aged ApoE-/- mice subjected to high-fat diet compared to WT mice on conventional diet51. Another study reports that high-fat diet

increases BP already after 12 weeks70. In contrast to the herein presented results, an earlier study suggested no differences in BP between aged ApoE-/- and WT mice on normal chow diet (140

± 7.6 mmHg in ApoE-/- mice and 136 ± 7.4 mmHg in WT mice)71. The study, however, did not assess BP differences between young and aged ApoE-/- mice. Considering the current knowledge in the

field, it remains to be further investigated whether or not changes in systemic BP contribute to the inflammatory and the brain phenotype described in this model. Furthermore, neither memory

impairment nor neuro-inflammation in our study were assessed longitudinally. However, our data convincingly show apparent memory deficits and obvious signs of neuro-inflammation and

-degeneration in ApoE-/- mice at the age of 12 months, which goes in line with findings of previously published studies38,39. It is therefore likely that the applied treatment regimens not

only attenuate but also reverse brain degeneration in aged ApoE-/- mice. In order to decipher cell type-specific treatment effects on circulating immune cells, systemic assessment of

different immune-related tissue compartments would be necessary. Moreover, understanding the mechanism of action by which simvastatin or other CVD therapeutics influence neuro-inflammatory

events and affect monocyte and macrophage polarization in vivo will require further investigation using more advanced single-cell techniques, which have recently provided important insight

into the plasticity of these cell types and the existence of a wide stimuli-driven network of myeloid cell behavior72,73 that may drastically impact neurological performance. In line with

that, it would be of interest how cholesterol- and BP-lowering therapies affect atherosclerosis progression (i.e., lesion size and plaque stability) in this model and to what extent this

affects memory functions. Although statins are thought to cause regression of atherosclerosis in humans, it has been shown that the amount of lesion regression is small compared with the

magnitude of the observed clinical benefit. Similarly, preclinical studies also showed beneficial statin effects on plaque stability in ApoE-/- mice74,75; however, there seems to be an

ongoing debate about their ability to actually reduce lesion size. Lastly, sex-specific differences need to be investigated as our study was solely performed in male mice. Especially since

previous studies convincingly showed an increased susceptibility of female mice to the development of cognitive impairment in response to chronic hypercholesterolemia38,39, treatment

responses may also differ sex-specifically. METHODS MATERIALS All chemical reagents and solutions were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Gll chem, Sweden), Saveen & Werner (Limhamn,

Sweden) or Sigma-Aldrich (Stockholm, Sweden) unless otherwise stated. Commercially available primary antibodies against CD3 (Bio-techne, UK), PSD-95, SNAP-25, NeuN and BDNF (Abcam, UK), CD68

(Invitrogen, Sweden), and Iba-1 (Wako, Japan) were used for immunofluorescence. Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, goat anti-rabbit, or goat anti-rat Fluor

594 (Nordic Biosite, Sweden) were used for visualization. Primers for qPCR were purchased from Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany). ANIMALS This investigation conforms to the Guide for Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals published by the European Union (Directive 2010/63/EU) and with the ARRIVE guidelines. All animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the institutional

animal ethics committees at the University of Barcelona (CEEA) and Lund University (5.8.18-12657/2017) and conducted in accordance with European animal protection laws. Male wild-type (WT)

C57Bl/6 J mice and Apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE-/-) mice (B6.129P2-Apoe (tm1Unc)/J) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and bred in a conventional animal facility under standard

conditions with a 12 h:12 h light-dark cycle, and access to food (standard rodent diet) and water ad libitum. Mice with a body weight BW ≥ 25 g were housed in groups of 4–5 in conventional

transparent polycarbonate cages with filter tops. ApoE-/- and C57Bl/6 J (WT) mice at the age of 4 and 12 months (_N_ = 10 per group) were used to assess the effect of ageing on inflammatory

status and brain phenotype (Fig. 1a). At the age of 12 months, another group of ApoE-/- mice was randomly assigned to the following experimental groups using the computer software _Research

Randomizer_ (http://www.randomizer.org/): aged control, aged + hydralazine (25 mg/L), aged + simvastatin (2.5 mg/L), and aged + hydralazine/simvastatin combination (_N_ = 10 for simvastatin

and hydralazine treatment; _N_ = 8 for combination treatment). The calculated doses given to the mice were 5 mg/kg/d for hydralazine and 0.5 mg/kg/d for simvastatin, which corresponds to 10

mg/kg/d and 20 mg/kg/d in humans, respectively (allometric scaling was used to convert doses amongst species76). Treatment was administered via drinking water over a course of two months.

The mice in this experimental cohort were 14 months of age at time of sacrifice (Fig. 2b). ApoE-/- mice at the age of 4 months were used as young controls (_N_ = 10). To ensure blinding,

experiments were performed after the animals and samples had received codes that did not reveal the identity of the treatment. In order to obey the rules for animal welfare, we designed

experimental groups in a way that minimizes stress for the animals and guarantees maximal information using the lowest group size possible when calculated with a type I error rate of _α_ =

0.05 (5%) and Power of 1-_β_ > 0.8 (80%) based on preliminary experiments. At termination, brain tissue was distributed to the different experiments as follows: Young (4 months) and aged

(12 months) WT and ApoE-/- mice (_N_ = 10 each) for flow cytometric assessment of one hemisphere, _N_ = 5 each for cortex and hippocampus fractionation of one hemisphere and _N_ = 5 for

whole hemisphere RNA and protein isolation (Fig. 1a). Young (4 months), aged (14 months), hydralazine- and simvastatin treated (_N_ = 5 each), and combination-treated (_N_ = 3) ApoE-/- mice

for whole brain cryo-sectioning, cortex and hippocampus fractionation of one hemisphere (_N_ = 5 each) as well as one hemisphere (_N_ = 5 each) for whole hemisphere RNA and protein isolation

(Fig. 2b). OPEN FIELD TESTING To test novel environment exploration, general locomotor activity, and screen for anxiety-related behavior mice were subjected to an open field exploration

task using a video tracking system and the computer software EthoVision XT® (Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands) as described before17. Mice were placed individually into an arena

(56 × 56 cm), which was divided into a grid of equally sized areas. The software recorded each line crossing as one unit of exploratory activity. The following behavioral parameters were

measured: activity, active time, mobile time, slow activity, mobile counts, and slow mobile counts. NOVEL OBJECT RECOGNITION (NOR) As previously described3,17,77, a NOR task was employed to

assess non-spatial memory components. Briefly, mice were habituated to the testing arena for 10 min over a period of 3 days. On test day, each mouse was exposed to two objects for 10 min. 5

min or 24 h later, mice were re-exposed to one object from the original test pair and to a novel object. The movements of the animal were video tracked with the computer software EthoVision

XT® (Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). A delay interval of 5 min was chosen to test short-term retention of object familiarity, and with a delay interval longer of 24 h, we tested

long-term hippocampus-dependent memory function3,78. OBJECT PLACEMENT TASK To test spatial recognition memory, mice were placed individually into an arena (56 × 56 cm). Each mouse was

exposed to two objects for 10 min. 5 min later, mice were re-exposed to both objects, of which one remained in the original place and the second object was moved to a novel place.

Exploration of the objects was assessed manually with a stopwatch when mice sniffed, whisked, or looked at the objects from no more than 1 cm away. The time spent exploring the objects in

new (novel) and old (familiar) locations was recorded during 5 min. BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENTS BP was measured in conscious mice using tail-cuff plethysmography (Kent Scientific, CODA, UK).

After a one-week handling period, mice were acclimatized to the restrainers and the tail cuff for a training period of 7 days. Data were recorded once mice presented with stable readings

over the course of one week. During BP measurements, 30 inflation cycles were recorded of which the first 14 were regarded as acclimatization cycles and only cycles 15–30 were included in

the analyses. FLUORESCENCE ACTIVATED CELL SORTING Whole blood from mice was collected in EDTA-coated tubes and red blood cells were lysed before samples were incubated in Fc block solution

followed by primary antibodies. After washing and centrifugation, the supernatant was decanted, and pellets were re-suspended in FACS buffer. Brain tissue was enzymatically digested and

homogenized. After density separation using Percoll (GE Healthcare), pellets were reconstituted in Fc block prior to staining with antibodies (Supplementary Table 5). Data acquisition was

carried out in a BD LSR Fortessa cytometer using FacsDiva software Vision 8.0 (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed with FlowJo software (version 10, TreeStar Inc., USA). Cells were

plotted on forward versus side scatter and single cells were gated on FSC-A versus FSC-H linearity. HISTOLOGY AND IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE Coronal brain sections (10 μm thickness) were incubated

with antibody against NeuN, BDNF, Iba-1, and CD68 (Supplementary Table 6). After several washes, sections were incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor-coupled antibodies (Life Technologies,

Sweden) at room temperature. Sections were then mounted in aqueous DAPI-containing media (DapiMount, Life Technologies, Sweden). The specificity of the immune staining was verified by

omission of the primary antibody and processed as above, which abolished the fluorescence signal. QUANTIFICATION OF IMMUNE-HISTOLOGICAL EXPERIMENTS For quantification of hippocampal NeuN+

cells, three regions of interest (ROI) in the cortex and three brain sections representing the hippocampus were selected. The number of NeuN+ cells in the pyramidal layer of the CA3 region,

of the CA1 region and the granule cell layer of the DG as well as in the cortical ROIs was determined using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.48 v, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). First, a binary image

was generated from the original images. To measure the total number of stained cells the analyze particle feature was chosen and the threshold was maintained at the level that is

automatically provided by the program, no size filter was applied. BDNF immune staining in the same three brain regions was quantified, and by dividing the obtained value by the

corresponding number of NeuN+ cells the ratio of BDNF per NeuN+ cell was obtained for the respective area. Staining was analyzed in three images per area and mouse. For each experimental

group _N_ = 5. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. BRAIN MACROPHAGE ANALYSIS Coronal brain sections (10 μm thickness) of each experimental group were immune-stained with Iba-1 (WAKO, Japan)

and CD68 (Invitrogen, Sweden). The total number of Iba-1+ cells was counted in two regions of the hippocampus (dentate gyrus; DG and the cornu ammonis 1; CA1) in each hemisphere and in five

ROIs of the cortex using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager.M2, Zeiss). The cells were classified into three activation state groups based on morphology where _Ramified_ (resting state)

denotes Iba-1+ cells with a small cell body and extensive branched processes, _Intermediate_ denotes Iba-1+ cells with enlarged cell body and thickened, reduced branches not longer than

twice the cell body length and _Round_ (active state) denotes Iba-1+ cells with round cell body without visible branches. In all sections, the total numbers of CD68 + Iba-1+ cells were

recorded. WESTERN BLOTTING For protein isolation, tissue lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton-X, 0.1% sodium-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS,

140 mM NaCl, and 25 μg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates underwent five freeze–thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen. The resulting lysates were centrifuged for 30 min at 15,000 _g_ and

4°C to remove insoluble material. Protein concentration was determined by PIERCE BCA protein assay. Western blotting was carried out according to standard protocols. Briefly, samples were

heated for 10 min at 95°C in sample buffer (2.0 ml 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% 14.7 M pH mercaptoethanol 12.5 mM EDTA, 0.02% bromophenol blue). Proteins were then

separated on 12% Bis-acrylamid mini gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Biorad, Sweden). The membranes were blocked for 60 min in 1% bovine serum albumin (in phosphate-buffered saline

containing 1% Tween 20 (PBST); 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.76 mM K2HPO4; pH 7.4) and sequentially incubated with the primary and secondary antibodies. An antibody-specific

dilution for the primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 7), and 1:40,000 for the HRP-labeled secondary antibody (BioNordika, Sweden) were utilized. All antibodies were diluted in 1% bovine

serum albumin or 5% milk in PBS-T. A standard chemiluminescence procedure (ECL Plus) was used to visualize protein binding. The developed membranes were evaluated densitometrically using

Image Lab 6.0.1 (Biorad, Sweden). All blots derive from the same experiment and were processed in parallel. QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME PCR (QPCR) RNA was isolated from brain tissue (_N_ = 5 per

group) using a Trizol® method. As per instructions using a “High-Capacity Reverse Transcriptase” kit (AB Bioscience, Stockholm, Sweden), 500 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed with

random hexamer primers. The resulting cDNA was diluted to a final volume of 250 μg and subsequently used as a template for qPCR reactions. qPCR was performed in triplicates using _Power_

SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technology, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each reaction comprised 2 ng cDNA, 3ul master mix and 0.2uM final concentration of each

primer (see list of primers; Supplementary Table 8). Cycling and detection were carried out using a CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System and data quantified using Sequence CFX

Manager™ Software (Biorad, Sweden). qPCR was performed for a total of 40 cycles (95°C 15 s, 60°C 60 s) followed by a dissociation stage. All data were normalized to species specific

housekeeping genes L14 (mouse) and GPI (human) and quantification was carried out via the absolute method using standard curves generated from pooled cDNA representative of each sample to be

analyzed. CELL CULTURE Bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated by culturing freshly isolated mouse bone marrow cells from C57Bl/6 J mice in IMDM medium (Gibco) supplemented

with 10% FCS (GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 U/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM glutamine and 20% (v/v) L929 conditional medium for 7 days. Human monocytic THP-1 cells (ATCC

#TIB-202) were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in large culture flasks. Cell cultures were maintained at

37°C with 5% CO2 and split 1:4 at a seeding density of 106 cells. For differentiation, THP-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells and treated with 2.5 ng/ml PMA

for 48 h. Prior to LPS activation and treatment, cells were allowed to rest in culture media for 24 h. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll-Paque Plus

(GE healthcare) density gradient centrifugation from donated blood of healthy volunteers. After centrifugation, the PBMC layers were isolated and washed with PBS to remove erythrocytes and

granulocytes. PBMCs purification was performed using anti-human CD14 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Monocytes were maintained in RPMI 1640

(Gibco) with 10% FCS (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). For macrophage differentiation and maturation, human monocytes were plated onto

tissue culture-treated 24-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well. The medium was supplemented with 100 ng/mL recombinant human M-CSF using CellXVivoTM kit (R&D Systems) and

differentiated for 5–7 days prior to use. Cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml LPS (Invitrogen, Sweden) for 6 h prior to a 12 h treatment with 1 µM simvastatin (Bio-techne, UK), 10 µM

hydralazine, and/or a combination of both. The concentrations were chosen based on the dosing regimen administered in the in vivo studies. After incubation, cells were detached using cold

PBS containing EDTA (5 mM) and either stained for flow cytometry or centrifuged and processed for RNA and protein isolation using the Trizol method. ELISA TNF-α and IL6 protein levels in

cell supernatant and plasma IL12/23 and IL17 protein levels were determined using DuoSet Elisa (R&D systems) as per manufacturer’s instruction. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS All data are

expressed as mean ± SEM, where _N_ is the number of animals or independent cell experiments. For comparisons of young and aged WT and ApoE-/- mice, two-way ANOVA with Sidak post hoc testing

was used to assess the effects of genotype and age. For comparison of multiple independent groups, the parametric one-way ANOVA test was used, followed by Tukey’s post hoc testing with exact

_P_-value computation. In case of non-normally distributed data (tested with Shapiro–Wilk test), the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc testing and exact _P_-value

computation was used for multiple comparisons. For comparison of two groups a two-tailed unpaired _t_-test was utilized. Differences were considered significant at error probabilities of _P_

≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Version 8.1.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc). REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature

Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary Material. REFERENCES *

Wimo, A. et al. The economic impact of dementia in Europe in 2008-cost estimates from the Eurocode project. _Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry_ 26, 825–832 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Meissner, A. Hypertension and the brain: a risk factor for more than heart disease. _Cerebrovasc. Dis._ 42, 255–262 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Meissner, A.,

Minnerup, J., Soria, G. & Planas, A. M. Structural and functional brain alterations in a murine model of Angiotensin II-induced hypertension. _J. Neurochem._ 140, 509–521 (2016). Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gasecki, D., Kwarciany, M., Nyka, W. & Narkiewicz, K. Hypertension, brain damage and cognitive decline. _Curr. Hypertens. Rep._ 15, 547–558 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moreira, E. L. et al. Age-related cognitive decline in hypercholesterolemic LDL receptor knockout mice (LDLr-/-): evidence of

antioxidant imbalance and increased acetylcholinesterase activity in the prefrontal cortex. _J. Alzheimers Dis._ 32, 495–511 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Vliet, P.

Cholesterol and late-life cognitive decline. _J. Alzheimers Dis._ 30, S147–S162 (2012). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hajjar, I. et al. Effect of antihypertensive therapy on

cognitive function in early executive cognitive impairment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. _Arch. Intern. Med._ 172, 442–444 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Rigaud, A. S., Olde-Rikkert, M. G., Hanon, O., Seux, M. L. & Forette, F. Antihypertensive drugs and cognitive function. _Curr. Hypertens. Rep._ 4, 211–215 (2002). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Peters, R. et al. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a

double-blind, placebo controlled trial._Lancet Neurol._ 7, 683–689 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jick, H., Zornberg, G. L., Jick, S. S., Seshadri, S. & Drachman, D. A.

Statins and the risk of dementia. _Lancet_ 356, 1627–1631 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rockwood, K. et al. Use of lipid-lowering agents, indication bias, and the risk of

dementia in community-dwelling elderly people. _Arch. Neurol._ 59, 223–227 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Suraweera, C., de Silva, V. & Hanwella, R. Simvastatin-induced

cognitive dysfunction: two case reports. _J. Med. Case Rep._ 10, 83 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wagstaff, L. R., Mitton, M. W., Arvik, B. M. & Doraiswamy,

P. M. Statin-associated memory loss: analysis of 60 case reports and review of the literature. _Pharmacotherapy_ 23, 871–880 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pietschmann, P. et al.

The effect of age and gender on cytokine production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and markers of bone metabolism. _Exp. Gerontol._ 38, 1119–1127 (2003). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Tan, Z. S. & Seshadri, S. Inflammation in the Alzheimer’s disease cascade: culprit or innocent bystander? _Alzheimer’s Res. Ther._ 2, 6 (2010). Article Google Scholar

* McRae, A., Dahlstrom, A., Polinsky, R. & Ling, E. A. Cerebrospinal fluid microglial antibodies: potential diagnostic markers for immune mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. _Behav.

Brain Res._ 57, 225–234 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Meissner, A. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha underlies loss of cortical dendritic spine density in a mouse model of

congestive heart failure. _J. Am. Heart Assoc_ 4, e001920 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Don-Doncow, N., Vanherle, L., Zhang, Y. & Meissner, A. T-cell

accumulation in the hypertensive brain: a role for Sphingosine-1-Phosphate-mediated chemotaxis. _Int. J. Mol. Sci._ 20, 537 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar * Alaarg, A.

et al. Multiple pathway assessment to predict anti-atherogenic efficacy of drugs targeting macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. _Vasc. Pharmacol._ 82, 51–59 (2016). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Sparrow, C. P. et al. Simvastatin has anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic activities independent of plasma cholesterol lowering. _Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol._ 21,

115–121 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rezaie-Majd, A. et al. Simvastatin reduces expression of cytokines interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 in circulating monocytes from hypercholesterolemic patients. _Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol._ 22, 1194–1199 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mullen, L., Ferdjani, J.

& Sacre, S. Simvastatin inhibits TLR8 signaling in primary human monocytes and spontaneous TNF production from rheumatoid synovial membrane cultures. _Mol. Med._ 21, 726–734 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rodrigues, S. F. et al. Hydralazine reduces leukocyte migration through different mechanisms in spontaneously hypertensive and

normotensive rats. _Eur. J. Pharmacol._ 589, 206–214 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Masliah, E. et al. Neurodegeneration in the central nervous system of apoE-deficient

mice. _Exp. Neurol._ 136, 107–122 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Aggarwal, S., Ghilardi, N., Xie, M. H., de Sauvage, F. J. & Gurney, A. L. Interleukin-23 promotes a

distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. _J. Biol. Chem._ 278, 1910–1914 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Damsker, J. M.,

Hansen, A. M. & Caspi, R. R. Th1 and Th17 cells: adversaries and collaborators. _Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci._ 1183, 211–221 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Patel, R. et al. Simvastatin induces regression of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improves cardiac function in a transgenic rabbit model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

_Circulation_ 104, 317–324 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Takemoto, M. et al. Statins as antioxidant therapy for preventing cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. _J.

Clin. Investig._ 108, 1429–1437 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ma, Y., Wang, J., Wang, Y. & Yang, G. Y. The biphasic function of microglia in ischemic

stroke. _Prog. Neurobiol._ 157, 247–272 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhou, T. et al. Microglia polarization with M1/M2 phenotype changes in rd1 mouse model of retinal

degeneration. _Front. Neuroanat._ 11, 77 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, F. et al. Acute hypoxia induced an imbalanced M1/M2 activation of microglia

through NF-kappaB signaling in Alzheimer’s disease mice and wild-type littermates. _Front. Aging Neurosci._ 9, 282 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar *

Bekinschtein, P. et al. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 105, 2711–2716 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Rodriguez-Cruz, A. et al. CD3(+) macrophages deliver proinflammatory cytokines by a CD3- and transmembrane TNF-dependent pathway and are increased at the BCG-infection site.

_Front. Immunol_. 10, 2550 (2019). * Whitmer, R. A., Sidney, S., Selby, J., Johnston, S. C. & Yaffe, K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. _Neurology_

64, 277–281 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zambon, D. et al. Higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment in familial hypercholesterolemia. _Am. J. Med._ 123, 267–274

(2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Arvanitakis, Z. et al. Statins, incident Alzheimer disease, change in cognitive function, and neuropathology. _Neurology_ 70,

1795–1802 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kivipelto, M. & Solomon, A. Cholesterol as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease—epidemiological evidence. _Acta Neurol. Scand.

Suppl._ 185, 50–57 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Raber, J. et al. Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice:

increased susceptibility of females. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 95, 10914–10919 (1998). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lane-Donovan, C. et al. Genetic restoration

of plasma ApoE improves cognition and partially restores synaptic defects in ApoE-deficient mice. _J. Neurosci._ 36, 10141–10150 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Caligiuri, G., Nicoletti, A., Zhou, X., Tornberg, I. & Hansson, G. K. Effects of sex and age on atherosclerosis and autoimmunity in apoE-deficient mice. _Atherosclerosis_ 145,

301–308 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Itani, H. A. et al. Activation of Human T Cells in hypertension: studies of humanized mice and hypertensive humans. _Hypertension_ 68,

123–132 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Iulita, M. F. et al. Differential effect of angiotensin II and blood pressure on hippocampal inflammation in mice. _J.

Neuroinflammation_ 15, 62 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ruiz-Magana, M. J. et al. The antihypertensive drug hydralazine activates the intrinsic pathway of

apoptosis and causes DNA damage in leukemic T cells. _Oncotarget_ 7, 21875–21886 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Januchowski, R. & Jagodzinski, P. P. Effect of

hydralazine on CD3-zeta chain expression in Jurkat T cells. _Adv. Med. Sci._ 51, 178–180 (2006). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Uetrecht, J. Current trends in drug-induced autoimmunity.

_Autoimmun. Rev._ 4, 309–314 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Arce, C. et al. Hydralazine target: from blood vessels to the epigenome. _J. Transl. Med._ 4, 10 (2006). Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Berg, K. E. et al. Elevated CD14++CD16- monocytes predict cardiovascular events. _Circulation. Cardiovasc. Genet._ 5, 122–131 (2012). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Meissner, A. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signalling-a key player in the pathogenesis of Angiotensin II-induced hypertension. _Cardiovasc. Res._ 113, 123–133

(2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Don-Doncow, N., Zhang, Y., Matuskova, H. & Meissner, A. The emerging alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate signalling and immune cells: from

basic mechanisms to implications in hypertension. _Br. J. Pharm._ 176, 1989–2001 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Faraco, G. et al. Dietary salt promotes neurovascular and cognitive

dysfunction through a gut-initiated TH17 response. _Nat. Neurosci._ 21, 240–249 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dinh, Q. N. et al. Advanced atherosclerosis is

associated with inflammation, vascular dysfunction and oxidative stress, but not hypertension. _Pharmacol. Res._ 116, 70–76 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yin, C. et al.

ApoE attenuates unresolvable inflammation by complex formation with activated C1q. _Nat. Med._ 25, 496–506 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yadav, A., Betts,

M. R. & Collman, R. G. Statin modulation of monocyte phenotype and function: implications for HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders. _J. Neurovirology_ 22, 584–596 (2016). Article

CAS Google Scholar * McFarland, A. J., Davey, A. K. & Anoopkumar-Dukie, S. Statins reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine and inflammatory mediator release in an in vitro model of

microglial-like cells. _Mediat. Inflamm._ 2017, 2582745 (2017). * Krysiak, R. & Okopien, B. Monocyte-suppressing effects of simvastatin in patients with isolated hypertriglyceridemia.

_Eur. J. Intern. Med._ 24, 255–259 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, X., Jin, J., Peng, X., Ramgolam, V. S. & Markovic-Plese, S. Simvastatin inhibits IL-17 secretion

by targeting multiple IL-17-regulatory cytokines and by inhibiting the expression of IL-17 transcription factor RORC in CD4+ lymphocytes. _J. Immunol._ 180, 6988–6996 (2008). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Arora, M. et al. Simvastatin promotes Th2-type responses through the induction of the chitinase family member Ym1 in dendritic cells. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_

103, 7777–7782 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hakamada-Taguchi, R. et al. Inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase reduces Th1 development

and promotes Th2 development. _Circulation Res._ 93, 948–956 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Marino, F. et al. Simvastatin treatment in subjects at high cardiovascular risk

modulates AT1R expression on circulating monocytes and T lymphocytes. _J. Hypertens._ 26, 1147–1155 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Krysiak, R. & Okopien, B. Different

effects of simvastatin on ex vivo monocyte cytokine release in patients with hypercholesterolemia and impaired glucose tolerance. _J. Physiol. Pharmacol._ 61, 725–732 (2010). CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Heart Protection Study Collaborative, G. Randomized trial of the effects of cholesterol-lowering with simvastatin on peripheral vascular and other major vascular outcomes

in 20,536 people with peripheral arterial disease and other high-risk conditions. _J. Vasc. Surg._ 45, 653–644 (2007). 645-654; discussion. Article Google Scholar * Shepherd, J. et al.

Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. _Lancet_ 360, 1623–1630 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Miron, V. E.

et al. Statin therapy inhibits remyelination in the central nervous system. _Am. J. Pathol._ 174, 1880–1890 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robin, N. C. et

al. Simvastatin promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis by enhancing Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. _Stem Cell Rep._ 2, 9–17 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Qiao, L. J., Kang, K. L.

& Heo, J. S. Simvastatin promotes osteogenic differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells via canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. _Mol. Cells_ 32, 437–444 (2011). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Esposito, E. et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin in an experimental model of spinal cord trauma: involvement of PPAR-alpha. _J.

Neuroinflammation_ 9, 81 (2012). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, J. et al. Atorvastatin treatment is associated with increased BDNF level and improved functional

recovery after atherothrombotic stroke. _Int. J. Neurosci._ 127, 92–97 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ludka, F. K. et al. Atorvastatin Protects from Abeta1-40-induced cell

damage and depressive-like behavior via ProBDNF Cleavage. _Mol. Neurobiol._ 54, 6163–6173 (2016). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hu, X., Song, C., Fang, M. & Li, C. Simvastatin

inhibits the apoptosis of hippocampal cells in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. _Exp. Ther. Med._ 15, 1795–1802 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kennedy, D. J. et al. CD36 and

Na/K-ATPase-alpha1 form a proinflammatory signaling loop in kidney. _Hypertension_ 61, 216–224 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hartley, C. J. et al. Hemodynamic changes in

apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. _Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol._ 279, H2326–H2334 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Xue, J. et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis

reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. _Immunity_ 40, 274–288 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Peet, C., Ivetic, A., Bromage, D. I. &

Shah, A. M. Cardiac monocytes and macrophages after myocardial infarction. _Cardiovasc. Res._ 116, 1101–1112 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nie, P. et al. Atorvastatin

improves plaque stability in ApoE-knockout mice by regulating chemokines and chemokine receptors. _PLoS ONE_ 9, e97009 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Bea, F.

et al. Simvastatin promotes atherosclerotic plaque stability in apoE-deficient mice independently of lipid lowering. _Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol._ 22, 1832–1837 (2002). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Nair, A. B. & Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. _J. Basic Clin. Pharm._ 7, 27–31 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Lidington, D. et al. CFTR therapeutics normalize cerebral perfusion deficits in mouse models of heart failure and subarachnoid hemorrhage. _JACC Basic Transl.

Sci._ 4, 940–958 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Baker, K. B. & Kim, J. J. Effects of stress and hippocampal NMDA receptor antagonism on recognition memory in

rats. _Learn. Mem._ 9, 58–65 (2002). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank Dr. Anna Planas for contributing aged ApoE-/-

mice and allowing us to use her behavioral platform, Francisca Ruiz for help with the treatment of the ApoE-/- mice and the support with Elisa experiments, Dr. Harry Björkbacka for providing

aged ApoE-/- mice and access to his flow cytometer, Yun Zhang for help with running some of the flow cytometry, and Dr. Joao Duarte for sharing antibodies for SNAP-25 and PSD-95. This work

was supported by the following funding sources: The Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation [2015.0030; AM]; Swedish Research Council [VR; 2017-01243; AM]; German Research Foundation [DFG; ME

4667/2-1; AM]; Åke Wibergs Stiftelse [M19-0380; AM]; Hedlund Stiftelse [M-2019-1101; AM], Inger Bendix Stiftelse [AM-2019-10; AM]; Stohnes Stiftelse [AM], Demensfonden [AM], Direktör Albert

Påhlsson Stiftelse [AM], and startup funds provided by the Wallenberg Centre for Molecular and Translational Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Sweden [AH]. FUNDING Open access funding

provided by Lund University. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Experimental Medical Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Nicholas Don-Doncow, Lotte Vanherle,

Frank Matthes, Hana Matuskova & Anja Meissner * Wallenberg Centre for Molecular Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Nicholas Don-Doncow, Lotte Vanherle, Frank Matthes, Hana Matuskova

& Anja Meissner * Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Wallenberg Centre for Molecular and Translational Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Lund, Sweden Sine Kragh Petersen &

Anetta Härtlova * Department of Neurology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany Hana Matuskova * German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Bonn, Germany Hana Matuskova & Anja

Meissner * Department of Clinical Science, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Sara Rattik Authors * Nicholas Don-Doncow View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Lotte Vanherle View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Frank Matthes View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sine Kragh Petersen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hana Matuskova View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sara Rattik View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anetta Härtlova View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anja Meissner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, N.D.D., S.R., L.V., F.M., H.M. and A.M.; validation, A.M. and A.H.; formal analysis, N.D.D., L.V., S.R. and A.M.; data curation, N.D.D., S.R., L.V.,

F.M., H.M., S.K.P., A.H. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, N.D.D., L.V., H.M., A.H. and A.M.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.M. and A.H.;

project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M. and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Anja

Meissner. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Don-Doncow, N., Vanherle, L., Matthes, F. _et al._

Simvastatin therapy attenuates memory deficits that associate with brain monocyte infiltration in chronic hypercholesterolemia. _npj Aging Mech Dis_ 7, 19 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-021-00071-w Download citation * Received: 09 November 2020 * Accepted: 28 May 2021 * Published: 04 August 2021 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-021-00071-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

Does neurovascular bundle preservation at the time of radical prostatectomy improve urinary continence?Access through your institution Buy or subscribe boxed-textBurkhard FC _ et al_. (2006) Nerve sparing open radical retro...

Bulk coca cola amazon deal that means they are less than 31p a canIF YOU WANT TO STOCK UP ON COCA COLA, AMAZON HAVE A GREAT DEAL 17:10, 21 May 2025 This article contains affiliate links,...

Page Not Found (404) | WFAE 90.7 - Charlotte's NPR News SourceWe're sorry; the page you're looking for cannot be found. Please use the search option at the top of the page to find wh...

Extra! Extra! Read all about it! | va phoenix health care | veterans affairsAre you missing out on what’s happening at the Phoenix VA Health Care System? Do you feel like the last one to know? Is ...

The fluxcom ensemble of global land-atmosphere energy fluxesABSTRACT Although a key driver of Earth’s climate system, global land-atmosphere energy fluxes are poorly constrained. H...

Latests News

Simvastatin therapy attenuates memory deficits that associate with brain monocyte infiltration in chronic hypercholesterolemiaABSTRACT Evidence associates cardiovascular risk factors with unfavorable systemic and neuro-inflammation and cognitive ...