Ovarian carcinosarcoma is a distinct form of ovarian cancer with poorer survival compared to tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma

Ovarian carcinosarcoma is a distinct form of ovarian cancer with poorer survival compared to tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Ovarian carcinosarcoma (OCS) is an uncommon, biphasic and highly aggressive ovarian cancer type, which has received relatively little research attention. METHODS We

curated the largest pathologically confirmed OCS cohort to date, performing detailed histopathological characterisation, analysis of features associated with survival and comparison against

high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC). RESULTS Eighty-two OCS patients were identified; overall survival was poor (median 12.7 months). In all, 79% demonstrated epithelial components

of high-grade serous (HGS) type, while 21% were endometrioid. Heterologous elements were common (chondrosarcoma in 32%, rhabdomyosarcoma in 21%, liposarcoma in 2%); chondrosarcoma was more

frequent in OCS with endometrioid carcinomatous components. Earlier stage, complete resection and platinum-containing adjuvant chemotherapy were associated with prolonged survival; however,

risk of relapse and mortality was high across all patient groups. Histological subclassification did not identify subgroups with distinct survival. Compared to HGSOC, OCS patients were older

(_P_ < 0.0001), more likely to be FIGO stage I (_P_ = 0.025), demonstrated lower chemotherapy response rate (_P_ = 0.001) and had significantly poorer survival (_P_ < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION OCS represents a distinct, highly lethal form of ovarian cancer for which new treatment strategies are urgently needed. Histological subclassification does not identify patient

subgroups with distinct survival. Aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered for all cases, including those with early-stage disease. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

CLINICAL FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PROGNOSIS IN LOW-GRADE SEROUS OVARIAN CARCINOMA: EXPERIENCES AT TWO LARGE ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS IN KOREA AND TAIWAN Article Open access 17 November 2020 A

LARGE-SCALE MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL STUDY EVALUATING PROGNOSTIC ASPECTS OF POSITIVE ASCITES CYTOLOGY AND EFFECTS OF THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS IN EPITHELIAL OVARIAN CANCER Article Open access 26

July 2021 HETEROGENEITY AND TREATMENT LANDSCAPE OF OVARIAN CARCINOMA Article 02 October 2023 BACKGROUND Ovarian carcinosarcoma (OCS)—previously also known as mixed malignant Müllerian

tumour—is an uncommon, highly aggressive cancer of the female genital tract [1]. Unlike more common ovarian cancers, OCS is biphasic, comprising malignant epithelial (carcinomatous) and

malignant mesenchymal (sarcomatous) populations. While it was originally thought that OCS may represent collisions of separate carcinomas and sarcomas [2, 3], molecular studies have revealed

a clonal relationship between these two malignant cell populations [4], pointing to a shared malignant ancestor cell. Much of our understanding of OCS is inferred from uterine

carcinosarcoma (UCS), a more common cancer in women [5]. However, it is well recognised that cancers presenting on the ovary bear stark clinical and molecular differences compared to those

of the uterus that demonstrate similar histology [6,7,8,9,10]. Indeed, limited available data suggest differences in the molecular landscape of OCS compared to UCS, though the number of

comprehensively characterised OCS samples to date is extremely low [4, 11]. OCS are highly heterogeneous, defined by the presence of both high-grade carcinomatous and high-grade sarcomatous

cell populations [12]. Carcinomatous elements may be of any ovarian high-grade carcinoma type (high-grade serous (HGS), endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous). The sarcomatous compartment may

be classified as homologous—demonstrating either non-specific appearance or differentiation native to the female genital tract—or heterologous, showing differentiation physiologically

foreign to the adnexa [1, 12]. The most common heterologous sarcomatous elements are chondroid (chondrosarcoma) and rhabdoid differentiation (rhabdomyosarcoma), with other heterologous

elements noted only in rare cases (angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma and liposarcoma; <5% of cases) [1, 12]. Despite its aggressive behaviour [13, 14], OCS has received relatively little

research attention to date. A limited number of studies have characterised an appreciable number of OCS patients in detail [15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, these studies have focussed on

describing patient outcome and typically have not performed contemporary pathology review to confirm OCS diagnosis; moreover, these studies have not described the histopathological

characteristics of cases in detail. Currently, detailed histopathological classification of the carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements is not routinely performed in OCS diagnosis. Little is

therefore known about the relationship between different histopathological features of OCS or whether these features are related to distinct clinical characteristics of OCS patients. We

sought to robustly curate a large cohort of OCS cases, performing detailed clinical and histopathological characterisation to improve our understanding of this highly aggressive tumour type.

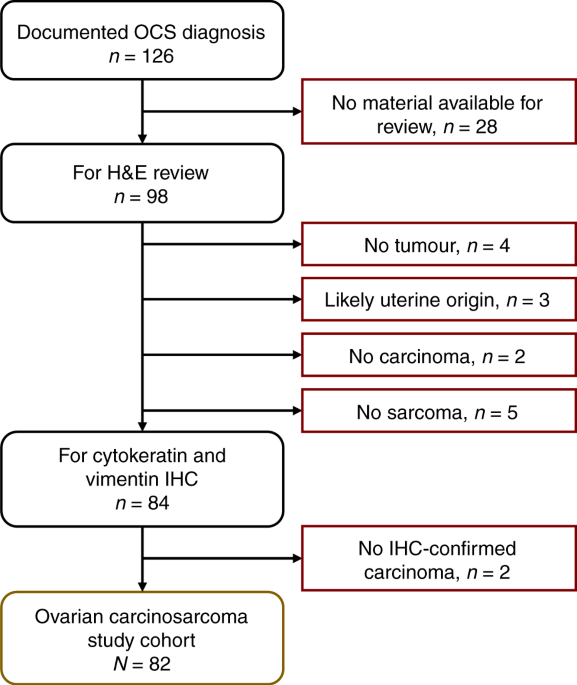

METHODS COHORT IDENTIFICATION AND CLINICAL ANNOTATION All ovarian cancer cases with a documented diagnosis of carcinosarcoma up to 31 December 2020 were identified from the Edinburgh

Ovarian Cancer Database (Fig. 1), wherein the details of diagnosis, treatment and outcome of all ovarian cancer patients treated at the Edinburgh Cancer Centre are entered prospectively as

part of routine care [21]. Baseline clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and outcome data were extracted. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of pathologically

confirmed diagnosis. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated as the time from pathologically confirmed diagnosis to recurrence/progression (Supplementary Methods Section 1). Response

to first-line adjuvant chemotherapy was evaluated using available radiological data (Supplementary Methods Section 1). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Lothian NRS Human

Annotated Bioresource (reference 15/ES/0094-SR1330) and the South East Scotland Cancer Information Research Governance Committee (reference CG/DF/E164-CIR21171). All participants gave

written informed consent or had consent waived by the ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study. PATHOLOGY REVIEW Of the 126 identified cases, archival formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material was available for 98 cases. Pathology review was performed by an expert gynaecological pathologist (CSH) using haematoxylin–eosin (H&E)-stained slides

from every available FFPE block. Available uterine samples were examined to confirm non-uterine origin (median 3 uterine blocks per case in the study cohort). A confirmatory observer (RLH)

was present for all review. Cases without a clear malignant high-grade carcinomatous or sarcomatous component on H&E review were excluded (minimum 5% sarcomatous and 5% carcinomatous

component required to be considered carcinosarcoma) (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cytokeratins and vimentin were used to confirm the presence of both carcinomatous and sarcomatous

compartments [1] (Supplementary Methods Section 2); cases without IHC-confirmed carcinoma and sarcoma were excluded (Fig. 1). Presence of endometriosis, squamous differentiation and serous

tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) were documented as part of pathology review. The relative prevalence of carcinomatous and sarcomatous compartments across all available samples was

documented (carcinoma-dominant: >70% carcinoma, sarcoma-dominant: >70% sarcoma, all others: mixed). Presence of carcinomatous and sarcomatous compartments in metastases (omentum and

distant sites) was recorded during review (carcinoma only, sarcoma only or mixed carcinosarcoma). CLASSIFICATION OF CARCINOMATOUS AND SARCOMATOUS ELEMENTS The histotype of the carcinomatous

compartment was determined by H&E review with IHC for WT1 and p53 in every case (Supplementary Methods Section 2) [22]. WT1 positivity was defined as positive tumour nuclei in

carcinomatous cells. p53 staining was classified as aberrant-positive (aberrant diffuse nuclear positivity), aberrant-null (diffusely negative nuclei with confirmed adjacent positive stromal

staining) or wild type (variable nuclear positivity) [23]. Heterologous sarcomatous elements were identified from the H&E-stained slides. Suspected chondrosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma

were confirmed using IHC for S100 (chondrosarcoma: nuclear S100-positive) and desmin/myogenin (rhabdomyosarcoma: nuclear desmin/myogenin-positive) (Supplementary Methods Section 2) [24].

Liposarcoma was identified by the presence of adipocytes with malignant nuclei and was distinguished specifically from benign adipose tissue infiltrated by carcinosarcoma. HIGH-GRADE SEROUS

OVARIAN CARCINOMA (HGSOC) COMPARATOR COHORT A cohort of 362 otherwise unselected patients with a confirmed diagnosis of HGSOC following contemporary pathology review was used as a comparator

cohort (Supplementary Methods Section 3) [25]. Characteristics of this cohort are summarised in Supplementary Table S1. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS All statistical analyses were performed using R

version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Comparisons of frequency were made using the chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous data were compared using

the Mann–Whitney _U_-test. Survival analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression models, presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%

CIs). All tests were two-sided; _P_ < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATISTICAL POWER The statistical power of survival analyses were estimated using the powerSurvEpi R

package. Power to detect a difference (HR = 0.50) between two OCS populations within the study cohort (50:50 split) was 83.7% (using the study cohort survival event rate of 95.1%). Power to

detect a survival difference (HR = 0.50) against the HGSOC comparator cohort (_N_ = 362, event rate 90.1%) was 99.0%. RESULTS PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS Of the 126 patients identified with a

documented diagnosis of OCS, 82 were included in the study cohort (_n_ = 32 no tumour material available for pathology review, _n_ = 5 no sarcoma identified on H&E review, _n_ = 2 no

carcinoma identified on H&E review, _n_ = 3 possible uterine origin, _n_ = 2 no confirmed cytokeratin-positive carcinoma) (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the study cohort are

summarised in Table 1. The majority of cases were International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III at diagnosis (51, 64.6% of evaluable cases; _n_ = 3 non-evaluable)

(Table 1). In all, 9 (11.4%), 8 (10.1%) and 11 (13.9%) cases were FIGO stages I, II and IV. Median age at diagnosis was 69 years (range 47–83). Four cases (4.9%) underwent neoadjuvant

chemotherapy. Median PFS was 9.6 months (95% CI 7.5–10.7). Median OS was 12.7 months (95% CI 9.2–17.1). For FIGO stage III/IV cases, the median OS was 11.9 months (95% CI 9.0–15.9).

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OCS The majority of OCS harboured an epithelial component of HGS type (all confirmed WT1 positive) (_n_ = 65, 79.3%) (Figs. 2 and 3); the remaining 17

cases (20.7%) were of endometrioid type (all confirmed WT1 negative). The vast majority of epithelial components had aberrant p53 expression patterns (wild-type pattern in 3 cases, 4.4% of

evaluable carcinomatous components) (Fig. 3). The majority of cases did not demonstrate a dominance of either the sarcomatous of carcinomatous population (67.5%, 54 of the 80 evaluable

cases); 16 (20.0%) were carcinoma-dominant (>70% malignant cells of epithelial type); 10 (12.5%) were sarcoma-dominant (>70% malignant cells of mesenchymal type) (Fig. 3). Heterologous

sarcomatous elements were identified in 42 cases (51.2%). The most common heterologous element was chondrosarcoma (31.7% of cases: 23 chondrosarcoma only, 3 chondrosarcoma plus

rhabdomyosarcoma); rhabdomyosarcoma was also common (20.7% of cases; 14 rhabdomyosarcoma only, 3 chondrosarcoma plus rhabdomyosarcoma) (Fig. 3). Chondrosarcoma was significantly

over-represented in OCS with endometrioid epithelial components (9 of 17, 52.9% in endometrioid versus 17 of 65 in HGS, 26.2%; _P_ = 0.044), with only one case demonstrating rhabdomyosarcoma

(with concurrent chondrosarcoma) (Fig. 3). By contrast, rhabdomyosarcoma was common in OCS with HGS epithelial components (16 of 65 cases, 24.6%). Two OCS (2.4%) demonstrated liposarcoma:

both had epithelial components of endometrioid type (_P_ = 0.041 for over-representation). Endometriosis was identified in four cases, all of which had carcinomatous components of

endometrioid type (Fig. 3); two were FIGO stage I and two were FIGO stage III. STIC lesions were identified in eight cases, all of which had HGS epithelial components; four were FIGO stage

III, two were stage I, one was stage IV, and one was unknown stage. Squamous differentiation was common in OCS with endometrioid carcinomatous components (35.3%, 6 of 17) but was also

identified in four OCS with epithelial components of HGS type (6.2%, 4 of 65, including 1 case with an identified STIC). The majority of cases with evaluable metastatic sites demonstrated

metastases comprising only the carcinomatous population (75.0%, 27 of 36), with a minority showing mixed carcinosarcoma (22.2%, 8 of 36); metastasis of pure sarcomatous population was rare

(2.8%, 1 of 36) (Fig. 3). FEATURES ASSOCIATED WITH PATIENT SURVIVAL OCS patients demonstrated similarly poor survival regardless of histological classification by carcinomatous (endometrioid

versus HGS) or sarcomatous compartments (homologous versus heterologous) (Fig. 4a). Achievement of no visible residual disease (NVRD) after surgical debulking was associated with

significantly prolonged OS (HR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.28–0.72) (Fig. 4b). Patients with stage I/II disease at diagnosis had significantly longer OS compared to stage III cases (HR = 0.48, 95% CI

0.27–0.87) (Fig. 4c). Age at diagnosis did not have a significant impact on survival (Fig. 4d). Survival time was longest in patients who received platinum–taxane chemotherapy, but this was

comparable to those receiving single-agent platinum or other platinum combinations (Fig. 4e). Multivariable analysis identified residual disease (RD) status, first-line treatment regime and

stage as independently associated with survival (Fig. 4f). COMPARISON OF OCS AND HGS OVARIAN CARCINOMA OCS patients were significantly older at diagnosis versus a comparator cohort of 362

unselected pathologically confirmed HGSOC patients (median 69 versus 61 years, _P_ < 0.0001) (Fig. 5a). A significantly greater proportion of OCS patients were diagnosed at FIGO stage I

(2.7-fold enrichment; 11.4%, 9 of the 79 evaluable OCS cases versus 4.3%, 15 of the 351 evaluable HGSOC cases; _P_ = 0.025) (Fig. 5b). The frequency of FIGO stage I cases was similar between

OCS with endometrioid and HGS carcinomatous components (11.8 and 11.3%, respectively). Differences in stage and age at diagnosis between OCS and HGSOC remained significant in a sensitivity

analysis including only OCS with carcinomatous components of HGS type (_P_ = 0.033 and _P_ < 0.0001, respectively). Response rate to first-line adjuvant chemotherapy was significantly

lower in OCS compared to HGSOC (42.1%, 8 of the 19 evaluable OCS versus 79.8%, 99 of the 124 evaluable HGSOC, _P_ = 0.001) (Fig. 5c). Multivariable analysis identified significantly shorter

survival time for OCS patients compared to HGSOC (multivariable HR for HGSOC versus OCS 0.31, 95% CI 0.23–0.40, _P_ < 0.0001) (Fig. 5d). The difference in survival remained significant in

a sensitivity analysis including only OCS who received platinum-containing chemotherapy (multivariable HR 0.42, _P_ < 0.0001). DISCUSSION OCS are rare, biphasic malignancies that have

received relatively little research attention to date. Although OCS is defined specifically as a biphasic tumour composed of high-grade epithelial and mesenchymal components, the

histopathological characteristics of OCS are highly heterogeneous. Here we present a large OCS cohort with detailed clinical annotation and histopathological characterisation. To our

knowledge, this is the largest pathologically confirmed OCS cohort reported to date. Most OCS cases demonstrated HGS epithelial components; however, OCS with endometrioid carcinomatous

components also represented a major population (around 20% of cases). Smaller studies have shown that the epithelial component is typically of HGS type, with other types representing only a

minority of cases [1]. In UCS, both serous-like and endometrioid-like UCS have been reported [26]. Most OCS cases did not demonstrate a dominant malignant cell population, with only 20 and

12.5% of cases demonstrating >70% carcinomatous and >70% sarcomatous populations. The observation that the majority of metastases were of pure carcinomatous populations is in line with

data demonstrating that most metastases from UCS are carcinomatous [26]. Around half of OCS cases demonstrated heterologous sarcomatous elements. Overall, both chondrosarcoma and

rhabdomyosarcoma were common, identified in 31.7 and 20.7% of cases, respectively. This is in contrast to UCS, where rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequent heterologous element (approximately

20% of cases), with only around 10% of cases demonstrating chondrosarcoma [27]. We observed a strong preference for chondrosarcoma over rhabdomyosarcoma in OCS with endometrioid epithelial

components (rhabdomyosarcoma identified in only one case, co-occurring with chondrosarcoma). Liposarcoma was rare, consistent with its low frequency in UCS (<5%) [27], and was only

observed in OCS demonstrating endometrioid epithelial components within our cohort. While squamous differentiation is typically an indicator of endometrioid carcinoma, and we show squamous

differentiation in some OCS harbouring an endometrioid epithelial component, we also identified squamous differentiation in OCS cases with HGS carcinomatous compartments, indicating that

squamous differentiation is not a specific feature of endometrioid tumours in this context. We identified endometriosis and STIC lesions in OCS with endometrioid and HGS carcinomatous

components, respectively. This is consistent with the notion that OCS likely represent metaplastic carcinomas, and with endometriosis and STIC lesions being common precursor lesions of

endometrioid and HGS ovarian carcinoma, respectively [28]. OCS may therefore arise through the same pathway as HGS (from the fallopian tube, via STIC) or endometrioid ovarian carcinoma (from

endometriosis). While the histology of the carcinomatous component is not associated with differential survival outcome, it is plausible that these features may be associated with distinct

molecular profiles, such as the likelihood of harbouring _BRCA1_/_2_ mutation, which in turn may determine efficacy of targeted agents including poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Endometriosis and STIC lesions were identified in the context of both early (FIGO I/II) and advanced stage (FIGO III/IV) cases. We demonstrate extremely poor survival in OCS patients, with

high risk of relapse and death across patients of all stages, ages and first-line management strategies. The median overall survival time across the study cohort was 12.7 months. Earlier

stage at diagnosis (FIGO I/II), undergoing platinum-containing adjuvant chemotherapy, and achievement of NVRD at debulking surgery were all associated with significantly prolonged survival

upon multivariable analysis; however, mortality rate was still high in these patient groups. These findings are in line with the importance of optimal debulking across ovarian carcinoma

types [21] and are in agreement with previous data suggesting improved survival in OCS with low RD volume [16,17,18]. Previous reports of smaller case numbers have suggested that presence of

heterologous elements may be an indicator of poorer prognosis in OCS [29, 30], though other investigators have reported no significant association [31, 32]. Histological subclassification

of patients based on the carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements did not identify patient groups with differential survival outcome in our cohort. These data suggest that subgrouping patients

by histological features is not a useful tool for risk stratification and highlight that specific histological features, such as the presence of heterologous sarcomatous elements, are not

markers of more aggressive disease. These data highlight the urgent need for improved treatment strategies for OCS patients. Some studies have investigated the potential role of ifosfamide

in OCS management; ifosfamide–paclitaxel chemotherapy appears inferior to platinum–taxane regimens [33], while the relative efficacy of platinum–ifosfamide versus platinum–taxane remains

controversial [1, 34, 35]. Moreover, ifosfamide-containing regimens may be less well tolerated [34, 36]. The rarity of OCS has impeded progress of OCS-specific clinical trials, with OCS

frequently included as a minor population alongside UCS. The GOG261 study of paclitaxel/ifosfamide versus carboplatin/paclitaxel demonstrated non-inferiority of the carboplatin–paclitaxel

regime in a mixed cohort of UCS and OCS [36], though the majority of cases were UCS (>80%). Progress toward discovery of effective molecularly targeted agents for OCS has been hindered by

lack of molecular characterisation in this tumour type, and this has impeded inclusion of OCS in clinical trials based on specific molecular defects, agnostic to disease site (BASKET

trials). Comprehensive molecular profiling to identify potentially actionable disease biology in OCS therefore represents an immediate research priority; specifically, genomic,

transcriptomic and proteomic characterisation of OCS cases has the potential to highlight disease biology already targeted by molecular therapeutics in other disease settings. Repurposing of

drugs already in use for other cancer types represents a strategy that may facilitate rapid translation of candidate agents into early phase trials. International collaboration will be

required to initiate disease-specific trials of OCS with sufficient power to inform future practice. Targeting of EGFR [37, 38], HER2 [37, 38], PDGFR [39, 40] and immunosuppressive molecules

[41] have been suggested as potential strategies from molecular studies of gynaecological carcinosarcomas; however, data are limited and the vast majority of data are derived from UCS,

rather than OCS. Molecular therapies routinely used for management of ovarian carcinoma may be of potential use in OCS; bevacizumab has demonstrated greatest efficacy in highest-risk ovarian

carcinoma cases [42], and may therefore be expected to benefit OCS patients, who are high risk by nature. Similarly, a minority of OCS are thought to harbour homologous recombination repair

pathway defects [11], and may therefore be sensitive to PARP inhibition [43]. Data regarding clinical efficacy of anti-angiogenic agents and PARP inhibitors in OCS are extremely limited. A

phase II trial of the anti-angiogenic agent aflibercept demonstrated disappointing activity in recurrent gynaecological carcinosarcoma [44]; however, this study included only three OCS

cases. While OCS were originally considered separate to epithelial ovarian cancer, it is now believed that OCS represent metaplastic carcinomas [3]. This has led many to consider OCS as

variants of HGSOC [45]: both are commonly diagnosed at advanced stage, together representing the most aggressive ovarian cancer types, and the majority of OCS harbour carcinomatous

components of HGS type. However, we demonstrate that OCS are around three times more likely to be diagnosed at FIGO stage I, are significantly older at diagnosis (median 69 years), show

significantly greater levels of intrinsic chemoresistance (response rate around 40%) and demonstrate significantly shorter survival compared to an unselected HGSOC population (multivariable

HR for HGSOC 0.31). Moreover, a significant proportion of OCS have an epithelial component of endometrioid type. These data suggest that consideration of OCS as variants of HGSOC is a

substantial over-simplification and that OCS in fact represent a distinct high-risk ovarian cancer type with unique clinical behaviour and histopathological characteristics. For forthcoming

trials where OCS may be included alongside high-grade endometrioid and HGS ovarian carcinoma, appropriate stratification is recommended. Major strengths of this work include contemporary

pathology review of a large cohort of cases (_n_ = 82), exclusion of cases with uterine origin and the use of IHC to confirm presence of both carcinomatous and sarcomatous populations, to

confirm the histotype of the carcinomatous elements and to confirm the presence of chondrosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. The majority of OCS studies have reported only a small number of cases

(typically fewer than 30) [1] with limited pathological assessment. The detailed clinical annotation and mature outcome data (event rate >90%) available for our cases—prospectively

collected as part of routine care—is another major strength, alongside the use of a pathologically confirmed HGSOC comparator cohort. Limitations include the retrospective nature of the

study and the extensive study period, with guidelines for ovarian cancer management evolving over this time. However, a long study period was essential for curating a sufficient number of

cases for meaningful analysis, which has represented a significant obstacle in previous studies. CONCLUSION OCS represents an extremely aggressive form of ovarian cancer, with distinct

clinical behaviour compared to HGSOC. OCS patients are poorly served by currently available treatment options, and new therapeutics strategies—which have been hindered by lack of research

attention and the relative rarity of OCS—are urgently required to improve patient outcomes. Absence of RD following debulking surgery and earlier stage at diagnosis are markers of improved

survival; however, risk of recurrence and mortality is high across all patient populations. While OCS are histopathologically heterogeneous, significant relationships exist between

phenotypes of the carcinomatous and sarcomatous compartments. Histological subclassification does not identify patient subgroups with distinct survival. DATA AVAILABILITY We are happy to

provide relevant data upon reasonable request, subject to compliance with the relevant ethical framework. REFERENCES * Boussios S, Karathanasi A, Zakynthinakis-Kyriakou N, Tsiouris AK,

Chatziantoniou AA, Kanellos FS, et al. Ovarian carcinosarcoma: current developments and future perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;134:46–55. Article PubMed Google Scholar *

McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:321–5. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * del Carmen

MG, Birrer M, Schorge JO. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:271–7. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Zhao S, Bellone S, Lopez S, Thakral D,

Schwab C, English DP, et al. Mutational landscape of uterine and ovarian carcinosarcomas implicates histone genes in epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

2016;113:12238. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Matsuzaki S, Klar M, Matsuzaki S, Roman LD, Sood AK, Matsuo K. Uterine carcinosarcoma: contemporary clinical summary,

molecular updates, and future research opportunity. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:586–601. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, et

al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bell D, Berchuck A, Birrer M, Chien J, Cramer DW, Dao F, et

al. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hollis RL, Thomson JP, Stanley B, Churchman M, Meynert AM, Rye T, et al.

Molecular stratification of endometrioid ovarian carcinoma predicts clinical outcome. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4995. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * McConechy MK, Ding J,

Senz J, Yang W, Melnyk N, Tone AA, et al. Ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas have distinct CTNNB1 and PTEN mutation profiles. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:128–34. Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Huang HN, Lin MC, Tseng LH, Chiang YC, Lin LI, Lin YF, et al. Ovarian and endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas have distinct profiles of microsatellite instability,

PTEN expression, and ARID1A expression. Histopathology. 2015;66:517–28. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gotoh O, Sugiyama Y, Takazawa Y, Kato K, Tanaka N, Omatsu K, et al. Clinically

relevant molecular subtypes and genomic alteration-independent differentiation in gynecologic carcinosarcoma. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4965. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Herrington CS. Muir’s textbook of pathology, 15 ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press-Taylor & Francis Group; 2014. * Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Kobel M, Harris HR, Berchuck A, Rossing MA, et

al. Invasive epithelial ovarian cancer survival by histotype and disease stage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:60–8. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rauh-Hain JA, Gonzalez R, Bregar AJ,

Clemmer J, Hernandez-Blanquisett A, Clark RM, et al. Patterns of care, predictors and outcomes of chemotherapy for ovarian carcinosarcoma: a National Cancer Database analysis. Gynecologic

Oncol. 2016;142:38–43. Article Google Scholar * Wang WP, Li N, Zhang YY, Gao YT, Sun YC, Ge L, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and lymphadenectomy in early-stage

ovarian carcinosarcoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1959–68. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lu CH, Chen IH, Chen YJ, Wang KL, Qiu JT, Lin H, et al. Primary treatment and

prognostic factors of carcinosarcoma of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: a Taiwanese Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:506–12. Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Harris MA, Delap LM, Sengupta PS, Wilkinson PM, Welch RS, Swindell R, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:654–7. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Rauh-Hain JA, Growdon WB, Rodriguez N, Goodman AK, Boruta DM 2nd, Schorge JO, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary: a case-control study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:477–81. Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Yalcin I, Meydanli MM, Turan AT, Taskin S, Sari ME, Gungor T, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary compared to ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma: impact of optimal

cytoreduction and standard adjuvant treatment. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:329–37. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Signorelli M, Chiappa V, Minig L, Fruscio R, Perego P, Caspani G, et al.

Platinum, anthracycline, and alkylating agent-based chemotherapy for ovarian carcinosarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1142–6. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Irodi A, Rye T, Herbert

K, Churchman M, Bartos C, Mackean M, et al. Patterns of clinicopathological features and outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer patients: 35 years of prospectively collected data. BJOG Int J

Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;127:1409–20. Article CAS Google Scholar * Kobel M, Rahimi K, Rambau PF, Naugler C, Le Page C, Meunier L, et al. An immunohistochemical algorithm for ovarian

carcinoma typing. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:430–41. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kobel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, Lui S, LePage C, Marass F, et al. Optimized p53

immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2:247–58. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Miettinen M.

Immunohistochemistry of soft tissue tumours - review with emphasis on 10 markers. Histopathology. 2014;64:101–18. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hollis RL, Meynert AM, Michie CO, Rye T,

Churchman M, Hallas-Potts A, et al. Multiomic characterisation of high grade serous ovarian carcinoma enables high resolution patient stratification. medRxiv:2022.01.07.22268840v1

[Preprint]. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 7]: [24 p.]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.07.22268840v1. * McConechy MK, Hoang LN, Chui MH, Senz J, Yang W, Rozenberg N,

et al. In-depth molecular profiling of the biphasic components of uterine carcinosarcomas. J Pathol. 2015;1:173–85. CAS Google Scholar * Kanthan R, Senger J-L. Uterine carcinosarcomas

(malignant mixed Müllerian tumours): a review with special emphasis on the controversies in management. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011;2011:470795. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Vaughan S, Coward JI, Bast RC, Berchuck A, Berek JS, Brenton JD, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:719–25. Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dictor M. Malignant mixed mesodermal tumor of the ovary: a report of 22 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:720–4. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sood

AK, Sorosky JI, Gelder MS, Buller RE, Anderson B, Wilkinson EJ, et al. Primary ovarian sarcoma: analysis of prognostic variables and the role of surgical cytoreduction. Cancer.

1998;82:1731–7. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Morrow CP, d’Ablaing G, Brady LW, Blessing JA, Hreshchyshyn MM. A clinical and pathologic study of 30 cases of malignant mixed

mullerian epithelial and mesenchymal ovarian tumors: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;18:278–92. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ariyoshi K, Kawauchi S, Kaku

T, Nakano H, Tsuneyoshi M. Prognostic factors in ovarian carcinosarcoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 23 cases. Histopathology. 2000;37:427–36. Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Brackmann M, Stasenko M, Uppal S, Erba J, Reynolds RK, McLean K. Comparison of first-line chemotherapy regimens for ovarian carcinosarcoma: a single institution

case series and review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:172. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rutledge TL, Gold MA, McMeekin DS, Huh WK, Powell MA, Lewin SN, et

al. Carcinosarcoma of the ovary-a case series. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006;100:128–32. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sit AS, Price FV, Kelley JL, Comerci JT, Kunschner AJ, Kanbour-Shakir A, et

al. Chemotherapy for malignant mixed Müllerian tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:196–200. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Powell MA, Filiaci VL, Hensley ML, Huang HQ,

Moore KN, Tewari KS, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel and carboplatin versus paclitaxel and ifosfamide in patients with carcinosarcoma of the uterus or ovary: an NRG oncology

trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:968–77. * Costa MJ, Walls J. Epidermal growth factor receptor and c-erbB-2 oncoprotein expression in female genital tract carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed

müllerian tumors). Clinicopathologic study of 82 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:533–42. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sawada M, Tsuda H, Kimura M, Okamoto S, Kita T, Kasamatsu T, et al.

Different expression patterns of KIT, EGFR, and HER-2 (c-erbB-2) oncoproteins between epithelial and mesenchymal components in uterine carcinosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:986–91. Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Adams SF, Hickson JA, Hutto JY, Montag AG, Lengyel E, Yamada SD. PDGFR-alpha as a potential therapeutic target in uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol.

2007;104:524–8. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Caudell JJ, Deavers MT, Slomovitz BM, Lu KH, Broaddus RR, Gershenson DM, et al. Imatinib mesylate (gleevec)–targeted kinases are

expressed in uterine sarcomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13:167–70. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hacking S, Chavarria H, Jin C, Perry A, Nasim M. Landscape of immune

checkpoint inhibition in carcinosarcoma (MMMT): analysis of IDO-1, PD-L1 and PD-1. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216:152847. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J,

Embleton A, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a

phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:928–36. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al.

Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495–505. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mackay HJ, Buckanovich RJ, Hirte H,

Correa R, Hoskins P, Biagi J, et al. A phase II study single agent of aflibercept (VEGF Trap) in patients with recurrent or metastatic gynecologic carcinosarcomas and uterine leiomyosarcoma.

A trial of the Princess Margaret Hospital, Chicago and California Cancer Phase II Consortia. Gynecologic Oncol. 2012;125:136–40. Article CAS Google Scholar * McCluggage WG. Morphological

subtypes of ovarian carcinoma: a review with emphasis on new developments and pathogenesis. Pathology. 2011;43:420–32. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the patients who contributed to this study and the Edinburgh Ovarian Cancer Database from which the clinical data reported here were retrieved. This work was

supported by a Tenovus Scotland Grant awarded to RLH (E19-11), and by the Nicola Murray Foundation. CB is supported by funding from Cancer Research UK. Sample collection was supported by

Cancer Research UK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre funding. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * The Nicola Murray Centre for Ovarian Cancer Research, Cancer Research UK

Scotland Centre, Institute of Genetics and Cancer, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK Robert L. Hollis, Ian Croy, Michael Churchman, Clare Bartos, Tzyvia Rye, Charlie Gourley

& C. Simon Herrington Authors * Robert L. Hollis View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ian Croy View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Michael Churchman View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Clare Bartos View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tzyvia Rye View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Charlie Gourley

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * C. Simon Herrington View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS RLH: conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation, funding acquisition, writing—original draft. IC: investigation, writing—review and

editing. MC: data curation, project administration, writing—review and editing. TR: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing. CB: data curation, writing—review and editing.

CG: resources, writing—review and editing CSH: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Robert L. Hollis. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING

INTERESTS RLH: consultancy fees from GSK outside the scope of this work. IC: none. MC: none. TR: none. CB: none. CG: CG: grants from AstraZeneca, MSD, BMS, Clovis, Novartis, BerGenBio,

Medannexin and Artios; personal fees from AstraZeneca, MSD, GSK, Tesaro, Clovis, Roche, Foundation One, Chugai, Takeda, Sierra Oncology, Takeda and Cor2Ed outside the submitted work; patents

PCT/US2012/040805 issued, PCT/GB2013/053202 pending, 1409479.1 pending, 1409476.7 pending and 1409478.3 pending. CSH: none. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE Ethical approval for

the study was obtained from the Lothian NRS Human Annotated Bioresource (reference 15/ES/0094-SR1330). All participants gave written informed consent or had consent waived by the ethics

committee due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION Not applicable. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

AJ CHECKLIST RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to

obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Hollis, R.L., Croy, I., Churchman, M. _et al._ Ovarian carcinosarcoma is a distinct form of ovarian cancer with poorer survival compared to tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma.

_Br J Cancer_ 127, 1034–1042 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01874-8 Download citation * Received: 01 February 2022 * Revised: 18 May 2022 * Accepted: 30 May 2022 * Published: 17

June 2022 * Issue Date: 05 October 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01874-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

'ice stupa' sculpts artificial glaciers to ensure fresh water supply in rural indiait’s a well known fact that due to global warming, glaciers are melting and causing sea levels to rise. YET ONE ENGINEER...

Big names need to click as india take on confident new zealand in 3rd odi - scoopwhoopStung by an improved New Zealand the other night, a wary India would like to quickly get their house in order when they ...

'i loved making it' carol vorderman gushes as fans praise her flying eThe 54-year-old TV star took to the social media site to thank fans for their support after the show went out last night...

Recisiun Finance - MediumSIMPLE WAYS TO SAVE, LET MONEY WORK FOR YOU! One of the biggest issues of our time is money. Let me put it this way, mon...

Off the menu special: new year's eve dining in newport beach - newport beach newsBY CHRISTOPHER TRELA AND CATHERINE DEL CASALE | NB INDY What are you doing New Year’s Eve? We have a few suggestions cou...

Latests News

Ovarian carcinosarcoma is a distinct form of ovarian cancer with poorer survival compared to tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinomaABSTRACT BACKGROUND Ovarian carcinosarcoma (OCS) is an uncommon, biphasic and highly aggressive ovarian cancer type, whi...

5 weeks pregnant: your body is changing! - times of indiaNow that the pregnancy has been confirmed, 5 weeks is the time for most women that they start feeling pregnant. With hor...

Lot polish airlines orders seven 787 dreamliners from boeingLOT Polish Airlines orders seven 787 Dreamliners from Boeing Warsaw-based LOT Polish Airlines has placed a firm order...

Prince william reflects on difficult break from kate - 'for the betterThe Duke of Cambridge said that, despite becoming immediately interested with one other, the pair spent time apart at th...

OBITUARY: Kevin M. Langdon | WTVB | 1590 AM · 95.5 FM | The Voice of Branch CountyOBITUARY: Kevin M. Langdon | WTVB | 1590 AM · 95.5 FM | The Voice of Branch County Close For the health and safety of ev...