Polygenic burden associated to oligodendrocyte precursor cells and radial glia influences the hippocampal volume changes induced by aerobic exercise in schizophrenia patients

Polygenic burden associated to oligodendrocyte precursor cells and radial glia influences the hippocampal volume changes induced by aerobic exercise in schizophrenia patients"

- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Hippocampal volume decrease is a structural hallmark of schizophrenia (SCZ), and convergent evidence from postmortem and imaging studies suggests that it may be explained by changes

in the cytoarchitecture of the cornu ammonis 4 (CA4) and dentate gyrus (DG) subfields. Increasing evidence indicates that aerobic exercise increases hippocampal volume in CA subfields and

improves cognition in SCZ patients. Previous studies showed that the effects of exercise on the hippocampus might be connected to the polygenic burden of SCZ risk variants. However, little

is known about cell type-specific genetic contributions to these structural changes. In this secondary analysis, we evaluated the modulatory role of cell type-specific SCZ polygenic risk

scores (PRS) on volume changes in the CA1, CA2/3, and CA4/DG subfields over time. We studied 20 multi-episode SCZ patients and 23 healthy controls who performed aerobic exercise, and 21

multi-episode SCZ patients allocated to a control intervention (table soccer) for 3 months. Magnetic resonance imaging-based assessments were performed with FreeSurfer at baseline and after

3 months. The analyses showed that the polygenic burden associated with oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC) and radial glia (RG) significantly influenced the volume changes between

baseline and 3 months in the CA4/DG subfield in SCZ patients performing aerobic exercise. A higher OPC- or RG-associated genetic risk burden was associated with a less pronounced volume

increase or even a decrease in CA4/DG during the exercise intervention. We hypothesize that SCZ cell type-specific polygenic risk modulates the aerobic exercise-induced neuroplastic

processes in the hippocampus. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS FITNESS IS POSITIVELY ASSOCIATED WITH HIPPOCAMPAL FORMATION SUBFIELD VOLUMES IN SCHIZOPHRENIA: A MULTIPARAMETRIC MAGNETIC

RESONANCE IMAGING STUDY Article Open access 16 September 2022 LOCUS FOR SEVERITY IMPLICATES CNS RESILIENCE IN PROGRESSION OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Article 28 June 2023 THE EFFECT OF FAMPRIDINE

ON WORKING MEMORY: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL BASED ON A GENOME-GUIDED REPURPOSING APPROACH Article Open access 08 November 2024 INTRODUCTION Hippocampal volume decrease has been

consistently reported in first- and multi-episode schizophrenia (SCZ) (e.g., refs. 1,2,3,4). This structural change has been associated with psychopathological severity and cognitive

deficits in SCZ patients5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Despite the relevance of both negative and cognitive symptoms for disability and functional recovery12, to date pharmacological strategies have shown

little success in the management of these symptoms13,14,15. An increasing body of evidence indicates that aerobic exercise as an add-on strategy may help to improve these disability-related

symptoms in SCZ patients16,17,18. Studies in the general population reported the beneficial effects of physical activity on cognitive performance and brain structure and function19,20,21,

and two recent meta-analyses of these studies provided remarkable evidence that aerobic exercise, including moderate-intensity continuous training, increases hippocampal volumes22,23. These

results suggest that neuroplastic processes in this brain region could drive symptom improvement in SCZ patients. The first study to investigate the effects of aerobic exercise on brain

structure in SCZ was performed in a small sample of multi-episode patients and reported an increase in hippocampal volume after 3 months of aerobic endurance training24. Subsequent studies

with similar designs could not replicate these structural findings16,17,18, however, although they did observe beneficial effects on patients’ global functioning17 and training-related

volume increases of the left superior, middle, and inferior anterior temporal gyri16. The type, intensity, and duration of the exercise intervention may explain the differences in the

results of the aforementioned studies, at least in part25,26,27. Recently, a study with a design that closely resembled the methodology of the above-mentioned first study in SCZ24 replicated

the positive effects of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in chronic SCZ patients28. Imaging studies that used automatic methods for hippocampus subfield segmentation recently revealed

that cornu ammonis (CA) regions CA1–4 and the dentate gyrus (DG) show more volume reduction than other hippocampal regions in both first-episode and chronic SCZ; the reductions are larger

in the left hemisphere and correlated to cognitive deficits29,30,31,32. Postmortem studies from our group confirmed these volumetric changes in the anterior and posterior hippocampus and

provided clues to understand the cytoarchitecture of these changes. We observed a decreased number of oligodendrocytes in the left and right CA4 (posterior hippocampus) and left CA4

(anterior hippocampus) and fewer neurons in the left DG33,34. Moreover, the number of oligodendrocytes correlated with the volume of CA434, and the reduction in the number of

oligodendrocytes in the left CA4 was more pronounced in patients with definitive cognitive deficits35. It is unknown, however, whether the number of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) or

mature oligodendrocytes is reduced. Impaired differentiation of OPCs has been hypothesized in SCZ36 and represents an interesting field for functional studies with patient-derived induced

pluripotent stem cells37. Radial glia (RG) cells are the common progenitors of neurons and oligodendrocytes, and during development they give rise to neurons and glia cells38. In the

hippocampus and cortex of adult mouse brains, they retain the capacity to differentiate to neurons, astrocytes, and also oligodendrocytes39. Late descendants of RG persist in the

subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the DG of the hippocampus, giving rise to adult neurogenesis and gliogenesis38. Direct evidence of

hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans remains difficult to capture and has even been questioned40. However, a recent study identified thousands of immature neurons in the DG of healthy

individuals up to the ninth decade of life, providing direct evidence of neurogenesis in adults41. The aforementioned cellular findings likely support the evidence of subfield-specific

effects of exercise. In first place, physical activity induces a volume increase in the left CA subregions and shows a trend for inducing a volume increase in the left CA4/DG42. In another

study, molecular, functional, and structural evidence from animal models indicated that exercise induces neuroplastic processes in the brain, particularly in the

hippocampus43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Finally, in a recent MRI/histological study in mice, physical exercise led to an increase in gray matter volume in the hippocampal DG and CA1–3

subfields, along with an increase in neurogenesis in the DG52. Taken together, these results provide mechanistic insight into the neuroplastic processes in specific areas of the hippocampus

that may link physical exercise to clinical improvement in SCZ. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWASs) indicate a large genetic overlap between SCZ risk and hippocampal volume53.

These results converge with previous evidence that a higher polygenic SCZ risk burden is associated with reduced hippocampal volumes in at-risk individuals and first-episode and chronic SCZ

patients4,54. Moreover, previous work from our group showed that polygenic SCZ risk modulates the effect of aerobic exercise in the CA4/DG region55. However, little is known about the

biological processes, cellular pathways, or cell types underlying the corresponding polygenic risk. In a recent single-cell RNAseq study, Skene et al. were able to map genomic SCZ risk loci

onto expression profiles of specific brain cell types; this mapping indicated that neuronal and OPC-enriched transcripts are associated with risk loci56. Here, we present a secondary

analysis that leverages the cell type-specific expression profiles derived from the study by Skene et al. to generate cell type-specific polygenic risk score (PRS) in our sample. Given the

previous postmortem evidence of decreased oligodendrocyte or OPC numbers in hippocampal subfields in SCZ33,34, our analysis focused on the polygenic burden associated with different stages

in the development of oligodendrocytes57,58, i.e., RG (PRSRad), OPCs (PRSOPC), and mature oligodendrocytes (PRSOli). Our aim was to investigate whether cell type-specific SCZ PRS related to

RG, OPCs, or mature oligodendrocytes are associated with volume changes in CA1, CA2/3, and CA4/DG subfields in multi-episode SCZ patients and healthy controls after 3 months of aerobic

exercise. PATIENTS AND METHODS PARTICIPANTS The sample analyzed in this study has been described in detail elsewhere17,18 and is the same as was previously used to determine the influence of

SCZ PRS on brain structure55. Briefly, the original study recruited 20 multi-episode SCZ patients and 23 healthy controls in an aerobic exercise intervention group and 21 multi-episode SCZ

patients in a table soccer (control intervention) group. It also included a cognitive remediation intervention for all participants. SCZ patients were recruited in the Department of

Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the University Medical Center Goettingen. Healthy controls, who had no past or current illness, were matched for age, sex, and handedness. The study protocol

was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Goettingen. All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study, and the study was

conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01776112). ENDURANCE TRAINING, TABLE SOCCER In each group, the intervention

consisted of three 30-min sessions per week and lasted 3 months. Endurance training was conducted on bicycle ergometers at an individually defined intensity that was gradually increased

until blood lactate concentrations of 2 mmol/l were reached, in accordance with the continuous training method (e.g., ref. 59). The training parameters blood lactate concentration, heart

rate, and exhaustion according to the Borg scale were monitored60. The SCZ patients allocated to the non-endurance intervention had table soccer for the same amount of time. More details on

the intervention protocols can be found elsewhere17,18. MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING ACQUISITION MRI data were acquired at baseline (V1) and after 3 months (V3) in a whole-body 3.0 Tesla MRI

Scanner (Magnetom TIM Trio, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with an 8-channel head coil. Small cushions were used between the head coil and the individuals’ heads to minimize head

movements. The 3D anatomical images were acquired with a T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence with a field-of-view of 256 mm and an isotropic spatial

resolution of 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm³ (TR = 2250 ms, echo time = 3.26 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, flip angle 9°, number of slices = 176). All images were quality controlled by a board-certified

radiologist and subsequently anonymized to blind the participants’ identities. IMAGE PROCESSING Automated hippocampal segmentation was performed with the FreeSurfer version 5.3.0 software

package (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The longitudinal processing stream was used for automatic subcortical segmentation, and hippocampal subfield volumes were computed from

T1-weighted images61. An unbiased within-subject template space and image62 was created by robust, inverse consistent registration63. Processing steps involved skull stripping, Talairach

transforms, atlas registration, and spherical surface maps. Parcellations were initialized with common information from the within-subject template, which significantly increased reliability

and statistical power61. The longitudinal processed images were used to calculate the CA1, CA2/3, and CA4/DG hippocampal subfield volumes for each participant64. We performed a correction

for the individual intracranial volume (ICV) with the proportions method, in which each T1 volume is divided by the participant’s ICV and multiplied by the average ICV of all participants65.

GENOTYPING AND QUALITY CONTROL DNA from all participants was genotyped with the Infinium PsychArray (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Quality control steps (inclusion thresholds: SNP call rate

>98%, subject call rate >98%, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium >0.001, heterozygosity rate within three standard deviations) were performed with PLINK 1.9

(www.cog-genomics.org/plink/1.9/)66. An identity-by-state (IBS) matrix was calculated to estimate the relationship between the samples and showed that the study samples were not related.

Ancestry differences between the study participants were modeled with the EIGENSOFT package (SmartPCA) by using a principal component analysis based on a pruned subset of ~50,000 autosomal

SNPs, after excluding regions with a high linkage disequilibrium67. All participants clustered to HapMap3 Caucasian reference populations, so none of them was excluded. We extracted the

first two ancestry principal components to correct for the potential effects of population substructure in all downstream analyses. IMPUTATION Genotype imputation was performed with

IMPUTE2/SHAPEIT by using its pre-phasing and imputation pipeline68,69. The 1000 Genomes Project dataset (Phase 3 integrated variant set) was used as the reference panel. Genetic variants

with a poor imputation quality (INFO < 0.7) were removed. After all quality control steps, 20 multi-episode SCZ patients and 20 healthy controls from the aerobic exercise intervention

groups and 16 multi-episode SCZ patients from the table soccer group were included in the genetic study. CALCULATION OF CELL TYPE-SPECIFIC PRS Discovery sample: Summary statistics from the

most recent SCZ GWAS, which was performed in a sample of 40,675 cases and 64,643 healthy controls, were used to ascertain risk variants/alleles, their p values, and associated odds ratios70.

Definition of oligodendrocyte lineage gene sets: The top 5% specifically expressed genes in mouse radial glia-like cells (Rad), OPCs, and mature oligodendrocytes (Oli), as published in the

recent single-cell RNAseq study mentioned above56, constituted the gene sets used to calculate PRS specific for these cell types (Supplementary Table 1). These gene sets had a certain degree

of overlap: Rad-OPC, 17.2%; OPC-Oli, 19.9%; and Rad-Oli, 3.2%. Target sample: Three different PRS were generated exclusively on the basis of the genetic variants in the genes (±10 kb) that

constitute the radial glia (PRSRad), OPCs (PRSOPC), and mature oligodendrocyte (PRSOli) gene sets. A clumping procedure was carried out (--clump-kb 500, --clump-r2 0.1) on the basis of the

variants of each gene set. PRS were calculated by multiplying the imputation dosage for each risk allele by the log(Odds Ratio) for each genetic variant. The resulting values were summed to

obtain an individual estimate of the cell type-specific SCZ genetic burden in each individual across ten p-value thresholds (5 × 10−8, 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2,

0.5, 1). STATISTICAL ANALYSES OF PRS EFFECTS ON HIPPOCAMPAL VOLUME CHANGES For each of the imaging variables under study, the baseline values (V1) were subtracted from the values at 3 months

(V3), and the resulting differences were standardized. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test found no significant deviations from a normal distribution for the hippocampal volume changes in CA1,

CA2/3, and CA4/DG. The effect of PRS on volume changes in CA1, CA2/3, and CA4/DG was ascertained by univariate linear regression in R 3.5.071. Age, sex, height, handedness, and the first two

ancestry principal components were used as covariates in all genetic association analyses. We performed all analyses separately for SCZ patients performing aerobic exercise, SCZ patients

playing table soccer, and healthy controls (who also performed aerobic exercise) to identify differences between the three groups. To address potential type I errors, we determined

statistical significance after a permutation-based resampling procedure. Briefly, empirical adjusted _p_ values (_P_adj) were determined through permutation testing of 10,000 simulations

with lmPerm package72. These _P_adj were obtained by permuting the values of the dependent variables in each of the tested models. Plots were generated with the ggplot2 package73. RESULTS

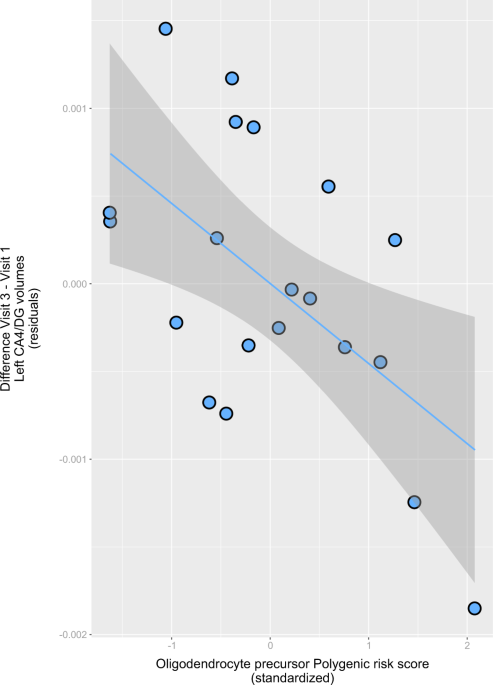

SCZ ENDURANCE TRAINING GROUP In the SCZ patients performing aerobic exercise, after correction (_P_adj < 0.05) the PRSOPC was significantly associated with volume changes in the left

CA4/DG subfield, with an optimal threshold identified at _p_ = 0.01 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). At all significant thresholds, high PRSOPC genetic risk burden was

associated with less pronounced volume increase or even a decrease over time in the left CA4/DG (Fig. 1). PRSRad analysis in this group showed a similar direction of the genetic effects, but

in this case changes associated with genetic load were observed in both the left and right CA4/DG subfields (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The optimal thresholds were 5 ×

10−8 (left) and 0.05 (right), and a high PRSRad genetic load was associated with a less pronounced volume increase or a decrease after exercise in left and right CA4/DG subfields (Fig. 2).

The study of the effects of PRSOli did not show any consistent effects in any of the subfields analyzed (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Likewise, PRSOPC and PRSRad did not influence volumes

changes in the CA1 or CA2/3 subfields (Supplementary Figs. 2,3). HEALTHY CONTROLS ENDURANCE TRAINING GROUP In the group of healthy controls performing the exercise intervention, the only

polygenic effect observed was an influence of PRSRad on volume changes after exercise in the left CA1 and left CA2/3 regions at several thresholds (_P_adj < 0.05) (Supplementary Figs. 2,

3). In both left subfields, a high PRSRad genetic load was associated with a less pronounced volume increase or a decrease after exercise (data not shown). SCZ TABLE SOCCER GROUP In the

group of SCZ patients performing the control intervention (table soccer), we found no consistent polygenic effects for any of the PRS in any of the hippocampal subfields (Supplementary Figs.

1–3). The only effects observed were single-threshold associations of PRSOPC with left and right CA4/DG volume changes, with opposite directions in the left and right hemispheres.

DISCUSSION Our results suggest that the beneficial effects of exercise in SCZ patients might be modulated by cell type-specific differential polygenic risk. Our approach builds upon previous

studies by our group: in brains from SCZ patients, we observed a reduced number of oligodendrocytes in the left CA4 region in stereological postmortem studies33,34 and, in the same samples,

showed a reduction (_p_ < 0.10) in the density of oligodendrocyte transcription factor (OLIG)1-positive cells by immunohistochemistry35. OLIG1-specific antibodies are known to stain

precursor forms and mature oligodendrocyte populations, and OLIG1 is needed for progenitor development and repair of myelin74. The above findings led us to hypothesize that the decreased

number of oligodendrocytes in the left CA4 region indicates a disturbed regenerative process75. Our group was the first to establish the role of SCZ PRS in changes in left hippocampal

subfields after sustained aerobic exercise55. Here, we extend these results and show that SCZ polygenic risk for certain cell types of the glial/oligodendrocyte lineage exerts a modulatory

effect on the CA4/DG volume changes promoted by exercise. In our study, polygenic risk associated to mature oligodendrocytes does not have any influence on these effects. This suggests that

the mechanism of action of these genetic modulatory effects likely involves neuroplastic processes involving gliogenesis (and potentially neurogenesis), or that at least these effects are

more important that the ones related to mature oligodendrocytes. Of note, a recent study in an animal model of toxin-induced demyelination showed that exercise enhances oligodendrogenesis

and remyelination and increases the proportion of remyelinated axons76. OPCs derived from RG cells display a widespread distribution in mammalian brains and serve as a source of myelinating

oligodendrocytes. Recent studies have provided compelling evidence that immature OPCs can differentiate to myelinating OPCs77,78. They likely represent the cellular substrate underlying

different forms of adult plasticity and form a homeostatic network capable of reacting to many types of injury79. Moreover, it is known that OPCs and oligodendrocytes not only generate

myelin but also provide trophic support to axons of principal neurons80,81. Also, parvalbuminergic interneurons are myelinated in the cortex and hippocampus of mice and humans, and a

dysfunctional cross-talk between these cells and oligodendrocytes has been suggested to contribute to the cellular pathology of SCZ82. It may thus be possible that disturbed oligodendrocyte

development leads to dysfunctions in interneurons, which is a highly replicated finding in SCZ83. On the basis of our findings, we hypothesize that high PRSOPC and PRSRad interfere with

neuroplastic changes triggered by aerobic exercise in SCZ patients and that these cell-specific PRS may lead to failed regeneration mechanisms in the hippocampus. An important proportion of

the variation on the hippocampus volume change triggered by exercise is explained by these polygenic estimates (optimal _R_² ~ 0.40 for PRSOPC and PRSRad). However not all variation is

explained by them and further studies are warranted to characterize the contribution of polygenic risk associated to neurons, astrocytes or microglia to such volumetric changes in these

patients. We could show that these effects are dependent on the disease status and the type of intervention. Our data indicate that in healthy controls PRS influence the effects of exercise

in CA1 and CA2/3 subfields, but not in CA4/DG. Moreover, we did not detect an effect in SCZ patients playing table soccer (control intervention), supporting the notion that the corresponding

PRS are relevant for the effects of aerobic exercise on brain structure. Our results suggest that genetics may shed some light on the conflicting evidence of the effects of aerobic exercise

on hippocampal volume and cognitive function in SCZ16,17,18,24,26,27,84. Here, the individual load of SCZ genetic risk seems to modulate the effects of aerobic exercise. This genetic

risk-driven modulation fits with the evidence of high heritability for the total hippocampus and its subfields85,86,87 and with a recent study showing a clear overlap between genetic factors

related to SCZ risk and hippocampal volume53. Moreover, a recent study of brain imaging phenotypes that used the UK Biobank cohort found that genes associated with brain development and

plasticity tend to be associated with mental disorders, including SCZ and severe depression, while genes coding for iron-related proteins tend to be associated with neurodegenerative

diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease88. Our study also has some limitations. First, the modest sample size of the original study warrants replication of our findings in independent

samples of SCZ patients who perform the same aerobic exercise intervention protocols and are assessed with the same instruments. Second, a randomization procedure was not used to allocate

the SCZ patients to the endurance training augmented with cognitive remediation or table soccer augmented with cognitive remediation group, which may have led to potential selection bias and

baseline differences in psychopathology and dose of antipsychotic medication17,18. Third, our exploratory analyses could not detect any effect of PRS on psychopathology, cognition or

functioning in our samples (data not shown), probably due to a limited sample size with low power to detect these genetic influences on behavioral outcomes. Finally, in order to confirm the

relatively high _R_2 estimates in the present study, replication studies are warranted in larger and independent samples. We conclude that a high polygenic burden may influence neuroplastic

processes in the hippocampus during aerobic exercise in SCZ. We propose a gene × environment interaction in which the genetic load influences the effects of the intervention on neuroplastic

processes via dysfunctions in RG and OPCs. Identifying the cell types that drive clinical improvement during aerobic exercise will provide mechanistic insight into the underlying biological

processes that direct hippocampal plasticity. REFERENCES * Adriano, F., Caltagirone, C. & Spalletta, G. Hippocampal volume reduction in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: a review

and meta-analysis. _Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry_ 18, 180–200 (2012). Google Scholar * van Erp, T. G. M. et al. Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028

individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 21, 547–553 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Okada, N. et al. Abnormal

asymmetries in subcortical brain volume in schizophrenia. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 21, 1460–1466 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Alnæs, D. et al. Brain heterogeneity

in schizophrenia and its association with polygenic risk. _JAMA Psychiatry_ https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0257 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Geisler, D. et al. Brain structure and function correlates of cognitive subtypes in schizophrenia. _Psychiatry Res_. 234, 74–83 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Hasan, A. et al. Hippocampal integrity and neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a multidimensional study. _World J. Biol. Psychiatry_ 15, 188–199 (2014). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Mitelman, S. A. et al. A comprehensive assessment of gray and white matter volumes and their relationship to outcome and severity in schizophrenia. _NeuroImage_ 37, 449–462

(2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Modinos, G. et al. Neuroanatomy of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a quantitative meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry

studies. _Cortex J. Devoted Study Nerv. Syst. Behav._ 49, 1046–1055 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Palaniyappan, L., Balain, V., Radua, J. & Liddle, P. F. Structural correlates of

auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. _Schizophr. Res_. 137, 169–173 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tamminga, C. A., Stan, A. D. & Wagner, A. D. The

hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 167, 1178–1193 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * van Tol, M.-J. et al. Voxel-based gray and white matter morphometry

correlates of hallucinations in schizophrenia: the superior temporal gyrus does not stand alone. _NeuroImage Clin._ 4, 249–257 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Green, M. F. Impact

of cognitive and social cognitive impairment on functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. _J. Clin. Psychiatry_ 77(Suppl 2), 8–11 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Goff,

D. C., Hill, M. & Barch, D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. _Pharm. Biochem Behav._ 99, 245–253 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Choi, K.-H., Wykes, T.

& Kurtz, M. M. Adjunctive pharmacotherapy for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: meta-analytical investigation of efficacy. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 203, 172–178 (2013). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Remington, G. et al. Treating negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an update. _Curr. Treat Options Psychiatry_ 3, 133–150 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Scheewe, T. W. et al. Exercise therapy, cardiorespiratory fitness and their effect on brain volumes: a randomised controlled trial in patients with schizophrenia

and healthy controls. _Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol._ 23, 675–685 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Malchow, B. et al. Effects of endurance training combined with cognitive

remediation on everyday functioning, symptoms, and cognition in multiepisode schizophrenia patients. _Schizophr. Bull._ 41, 847–858 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Malchow, B. et al. Effects of endurance training on brain structures in chronic schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. _Schizophr. Res_. 173, 182–191 (2016). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Erickson, K. I. & Kramer, A. F. Aerobic exercise effects on cognitive and neural plasticity in older adults. _Br. J. Sports Med_. 43, 22–24 (2009). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Erickson, K. I. et al. Physical activity predicts gray matter volume in late adulthood: the Cardiovascular Health Study. _Neurology_ 75, 1415–1422 (2010). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Erickson, K. I. et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 108, 3017–3022 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, M.-Y. et al. The effects of aerobic exercise on the structure and function of DMN-related brain regions: a systematic review. _Int

J. Neurosci._ 127, 634–649 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Feter, N., Penny, J. C., Freitas, M. P. & Rombaldi, A. J. Effect of physical exercise on hippocampal volume in

adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. _Sci. Sports_ 33, 327–338 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Pajonk, F.-G. et al. Hippocampal plasticity in response to exercise in

schizophrenia. _Arch. Gen. Psychiatry_ 67, 133–143 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Malchow, B. et al. The effects of physical exercise in schizophrenia and affective disorders.

_Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci._ 263, 451–467 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Firth, J., Cotter, J., Elliott, R., French, P. & Yung, A. R. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. _Psychol. Med_. 45, 1343–1361 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Firth, J. et al. Aerobic exercise improves

cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. _Schizophr. Bull_. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw115 (2016). * Woodward, M. L. et al.

Hippocampal volume and vasculature before and after exercise in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. _Schizophr. Res_. 202, 158–165 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Haukvik, U.

K., Tamnes, C. K., Söderman, E. & Agartz, I. Neuroimaging hippocampal subfields in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. _J. Psychiatr. Res._ 104,

217–226 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Baglivo, V. et al. Hippocampal subfield volumes in patients with first-episode psychosis. _Schizophr. Bull._ 44, 552–559 (2018). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Haukvik, U. K. et al. In vivo hippocampal subfield volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 77, 581–588 (2015). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Vargas, T. et al. Hippocampal subregions across the psychosis spectrum. _Schizophr. Bull._ 44, 1091–1099 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Falkai, P. et al. Decreased

Oligodendrocyte and Neuron Number in Anterior Hippocampal Areas and the Entire Hippocampus in Schizophrenia: A Stereological Postmortem Study. _Schizophr. Bull._ 42(Suppl 1), S4–S12 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schmitt, A. et al. Stereologic investigation of the posterior part of the hippocampus in schizophrenia. _Acta Neuropathol._ 117, 395–407

(2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Falkai, P. et al. Oligodendrocyte and interneuron density in hippocampal subfields in schizophrenia and association of oligodendrocyte number with

cognitive deficits. _Front Cell Neurosci._ 10, 78 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Mauney, S. A., Pietersen, C. Y., Sonntag, K.-C., Woo & T-UW.

Differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors is impaired in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. _Schizophr. Res_. 169, 374–380 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Raabe, F. J. et al. Studying and modulating schizophrenia-associated dysfunctions of oligodendrocytes with patient-specific cell systems. _NPJ Schizophr._ 4, 23 (2018). Article PubMed

PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Faissner, A. & Reinhard, J. The extracellular matrix compartment of neural stem and glial progenitor cells. _Glia_ 63, 1330–1349 (2015). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Markó, K. et al. Isolation of radial glia-like neural stem cells from fetal and adult mouse forebrain via selective adhesion to a novel adhesive peptide-conjugate.

_PLoS ONE_ 6, e28538 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Sorrells, S. F. et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in

adults. _Nature_ 555, 377–381 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moreno-Jiménez, E. P. et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically

healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. _Nat. Med._ https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0375-9 (2019). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Rosano, C. et

al. Hippocampal response to a 24-month physical activity intervention in sedentary older adults. _Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry_ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.007 (2016). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Biedermann, S. et al. In vivo voxel based morphometry: detection of increased hippocampal volume and decreased glutamate levels in exercising mice.

_NeuroImage_ 61, 1206–1212 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * O’Callaghan, R. M., Ohle, R. & Kelly, A. M. The effects of forced exercise on hippocampal plasticity in the rat: a

comparison of LTP, spatial- and non-spatial learning. _Behav. Brain Res._ 176, 362–366 (2007). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Vasuta, C. et al. Effects of exercise on NMDA receptor

subunit contributions to bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the mouse dentate gyrus. _Hippocampus_ 17, 1201–1208 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stranahan, A. M., Khalil,

D. & Gould, E. Running induces widespread structural alterations in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. _Hippocampus_ 17, 1017–1022 (2007). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Zhao, C., Teng, E. M., Summers, R. G., Ming, G.-L. & Gage, F. H. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. _J.

Neurosci._ 26, 3–11 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tong, L., Shen, H., Perreau, V. M., Balazs, R. & Cotman, C. W. Effects of exercise on gene-expression

profile in the rat hippocampus. _Neurobiol. Dis._ 8, 1046–1056 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Praag, H., Kempermann, G. & Gage, F. H. Running increases cell

proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. _Nat. Neurosci._ 2, 266–270 (1999). Article PubMed Google Scholar * van Praag, H., Shubert, T., Zhao, C. & Gage, F. H.

Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. _J. Soc. Neurosci._ 25, 8680–8685 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Farmer, J. et al. Effects of voluntary

exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo. _Neuroscience_ 124, 71–79 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Sack, M. et al. Early effects of a high-caloric diet and physical exercise on brain volumetry and behavior: a combined MRI and histology study in mice. _Brain Imaging Behav._ 11, 1385–1396

(2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Smeland, O. B. et al. Genetic overlap between schizophrenia and volumes of hippocampus, putamen, and intracranial volume indicates shared molecular

genetic mechanisms. _Schizophr. Bull._ 44, 854–864 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Harrisberger, F. et al. Impact of polygenic schizophrenia-related risk and hippocampal volumes

on the onset of psychosis. _Transl. Psychiatry_ 6, e868 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Papiol, S. et al. Polygenic risk has an impact on the structural

plasticity of hippocampal subfields during aerobic exercise combined with cognitive remediation in multi-episode schizophrenia. _Transl. Psychiatry_ 7, e1159 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Skene, N. G. et al. Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. _Nat. Genet_. 50, 825–833 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Bergles, D. E. & Richardson, W. D. Oligodendrocyte development and plasticity. _Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol._ 8, a020453 (2015). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * van Tilborg, E. et al. Origin and dynamics of oligodendrocytes in the developing brain: implications for perinatal white matter injury. _Glia_ 66, 221–238 (2018). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Kenney, W. L., Wilmore, J. H. & Costill, D. L. _Physiology of Sport and Exercise with Web Study Guide_, _5th edn_. (Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, 2011. * Borg,

G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. _Scand. J. Rehabil. Med_. 2, 92–98 (1970). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Reuter, M., Schmansky, N. J., Rosas, H. D. & Fischl,

B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. _NeuroImage_ 61, 1402–1418 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Reuter, M. & Fischl, B. Avoiding

asymmetry-induced bias in longitudinal image processing. _NeuroImage_ 57, 19–21 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Reuter, M., Rosas, H. D. & Fischl, B. Highly accurate inverse

consistent registration: a robust approach. _NeuroImage_ 53, 1181–1196 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Van Leemput, K. et al. Automated segmentation of hippocampal subfields from

ultra-high resolution in vivo MRI. _Hippocampus_ 19, 549–557 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Brien, L. M. et al. Statistical adjustments for brain size in

volumetric neuroimaging studies: some practical implications in methods. _Psychiatry Res._ 193, 113–122 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chang, C. C. et al.

Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. _GigaScience_ 4, 7 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Price, A. L. et al.

Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. _Nat. Genet_. 38, 904–909 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Howie, B. N.,

Donnelly, P. & Marchini, J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. _PLoS Genet._ 5, e1000529 (2009). Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Delaneau, O., Zagury, J.-F. & Marchini, J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. _Nat. Methods_ 10,

5–6 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pardiñas, A. F. et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background

selection. _Nat. Genet._ https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical

computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015). * Wheeler, B. lmPerm: Permutation tests for linear models. R package version 1.

2010https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lmPerm. * Wickham, H. _ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis._ (Springer-Verlag, New York, NY, US, 2009). Book Google Scholar * Arnett, H. A.

et al. bHLH transcription factor Olig1 is required to repair demyelinated lesions in the CNS. _Science_ 306, 2111–2115 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Falkai, P. et al.

Kraepelin revisited: schizophrenia from degeneration to failed regeneration. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 20, 671–676 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jensen, S. K. et al. Multimodal

enhancement of remyelination by exercise with a pivotal role for oligodendroglial PGC1α. _Cell Rep._ 24, 3167–3179 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Miron, V. E., Kuhlmann, T.

& Antel, J. P. Cells of the oligodendroglial lineage, myelination, and remyelination. _Biochim. Biophys. Acta_ 1812, 184–193 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fard M. K. et

al. BCAS1 expression defines a population of early myelinating oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions. _Sci. Transl. Med_. 9. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7816 (2017).

Article PubMed CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dimou, L. & Gallo, V. NG2-glia and their functions in the central nervous system. _Glia_ 63, 1429–1451 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nave, K.-A. Myelination and support of axonal integrity by glia. _Nature_ 468, 244–252 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Snaidero, N.

et al. Antagonistic functions of MBP and CNP establish cytosolic channels in CNS Myelin. _Cell Rep._ 18, 314–323 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stedehouder,

J. & Kushner, S. A. Myelination of parvalbumin interneurons: a parsimonious locus of pathophysiological convergence in schizophrenia. _Mol. Psychiatry_ 22, 4–12 (2017). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Konradi, C. et al. Hippocampal interneurons are abnormal in schizophrenia. _Schizophr. Res_. 131, 165–173 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Dauwan, M., Begemann, M. J. H., Heringa, S. M. & Sommer, I. E. Exercise improves clinical symptoms, quality of life, global functioning, and depression in schizophrenia: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. _Schizophr. Bull._ 42, 588–599 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Whelan, C. D. et al. Heritability and reliability of automatically segmented human

hippocampal formation subregions. _NeuroImage_ 128, 125–137 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * den Braber, A. et al. Heritability of subcortical brain measures: a perspective for

future genome-wide association studies. _NeuroImage_ 83, 98–102 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Roshchupkin, G. V. et al. Heritability of the shape of subcortical brain structures in the

general population. _Nat. Commun._ 7, 13738 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elliott, L. T. et al. Genome-wide association studies of brain imaging phenotypes

in UK Biobank. _Nature_ 562, 210–216 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was funded by the following grants from

the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG): Klinische Forschergruppe (KFO) 241: TP1 (SCHU 1603/5-1; BI576/5-1), and PsyCourse (SCHU 1603/7-1; FA241/16-1). Further funding was received from

the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the research network on psychiatric diseases ESPRIT (grant number 01EE1407E). S.P. was supported by a 2016 NARSAD Young

Investigator Grant (25015) from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. F.R. was supported by the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung foundation. The authors thank Jacquie Klesing, BMedSci

(Hons), Board-certified Editor in the Life Sciences (ELS), for editing assistance with the manuscript. Ms. Klesing received compensation for her work from the LMU Munich, Germany. AUTHOR

INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Berend Malchow, Peter Falkai AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital, Nussbaumstrasse 7, 80336,

Munich, Germany Sergi Papiol, Daniel Keeser, Alkomiet Hasan, Thomas Schneider-Axmann, Florian Raabe, Moritz J. Rossner, Andrea Schmitt, Berend Malchow & Peter Falkai * Institute of

Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG), University Hospital, Ludwig Maximilian University, Nussbaumstrasse 7, 80336, Munich, Germany Sergi Papiol * Institute of Clinical Radiology, Ludwig

Maximilian University Munich, Marchioninistrasse 15, 81377, Munich, Germany Daniel Keeser * International Max Planck Research School for Translational Psychiatry, Kraepelinstr. 2-10, 80804,

Munich, Germany Florian Raabe * Institute of Human Genetics, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany Franziska Degenhardt * Department of Genetic Epidemiology, University Medical Center,

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Humboldtallee 32, 37073, Göttingen, Germany Heike Bickeböller * German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Feodor-Lynen Str. 17, 81377, Munich,

Germany Ludovico Cantuti-Castelvetri & Mikael Simons * Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (SyNergy), 81377, Munich, Germany Mikael Simons * Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology,

Technical University Munich, 80805, Munich, Germany Mikael Simons * Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, County Hospitals Darmstadt-Dieburg, Krankenhausstrasse 7, 64823, Groß-Umstadt,

Germany Thomas Wobrock * Laboratory of Neuroscience (LIM27), Institute of Psychiatry, University of Sao Paulo, Rua Dr. Ovídio Pires de Campos 785, Sao Paulo-SP, 05403-903, Brazil Andrea

Schmitt Authors * Sergi Papiol View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Daniel Keeser View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alkomiet Hasan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thomas Schneider-Axmann View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Florian Raabe View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Franziska Degenhardt View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Moritz J. Rossner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Heike Bickeböller View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ludovico Cantuti-Castelvetri View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mikael Simons View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thomas Wobrock View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrea Schmitt View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Berend Malchow View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Peter Falkai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Sergi Papiol. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST S.P., D.K., T.S.-A., H.B., F.R., M.J.R. and B.M. report no conflicts of interest. A.H. has received paid speakerships

from Lundbeck, Janssen, Otsuka, Desitin, and Pfizer and was a member of the advisory boards of Lunbeck, Janssen, Roche, and Otsuka. T.W. has received speaker honoraria from Alpine Biomed,

Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, I3G, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Lundbeck, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Otsuka, and Pfizer, was a member of the advisory boards of Janssen-Cilag and

Otsuka/Lundbeck and has received restricted research grants from AstraZeneca, Cerbomed, I3G, and AOK (health insurance company). A.S. has been an honorary speaker for TAD Pharma and Roche

and a member of the advisory board for Roche. P.F. has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: Abbott, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Essex,

Lundbeck, Otsuka, Gedeon Richter, Servier, Takeda, the German Ministry of Science, and the German Ministry of Health. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and

your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this

license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Papiol, S., Keeser, D., Hasan, A. _et al._ Polygenic burden

associated to oligodendrocyte precursor cells and radial glia influences the hippocampal volume changes induced by aerobic exercise in schizophrenia patients. _Transl Psychiatry_ 9, 284

(2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0618-z Download citation * Received: 20 May 2019 * Revised: 10 September 2019 * Accepted: 03 October 2019 * Published: 11 November 2019 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0618-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Trending News

Aarp policy leaders named as next avenue's 2016 top 50+ influencersDebra Whitman, AARP's EVP and Chief Public Policy Officer, and Susan Reinhard, SVP and Director of AARP's Pubi...

Feeling angry as a family caregiver? You are not aloneBeing a caregiver means dealing with a kaleidoscope of emotions on any given day. Thankfully, we live in an age when it’...

Genetic analyses of pupation distance in Drosophila melanogasterThe inheritance of Drosophila melanogaster larval pupation behaviour is investigated in sixteen reciprocal crosses betwe...

Agmatine Potentiates the Analgesic Effect of Morphine by an α2-Adrenoceptor-Mediated Mechanism in MiceThe effects of agmatine, which is an endogenous polyamine metabolite formed by decarboxylation of L-arginine, and a comb...

Something went wrong, sorry. :(Sex differences in biological substrates of drug use and addiction are poorly understood. The present study investigated...

Latests News

Polygenic burden associated to oligodendrocyte precursor cells and radial glia influences the hippocampal volume changes induced by aerobic exercise iABSTRACT Hippocampal volume decrease is a structural hallmark of schizophrenia (SCZ), and convergent evidence from postm...

In-plane coherent control of plasmon resonances for plasmonic switching and encodingABSRACT Considerable attention has been paid recently to coherent control of plasmon resonances in metadevices for poten...

Digital health technologies: opportunities and challenges in rheumatologyABSTRACT The past decade in rheumatology has seen tremendous innovation in digital health technologies, including the el...

The page you were looking for doesn't exist.You may have mistyped the address or the page may have moved.By proceeding, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and our ...

Ajax chief claims jordan henderson 'didn't feel wanted from minute one'JORDAN HENDERSON WAS LAST WEEK LINKED WITH A MOVE TO AS MONACO FROM MONACO 13:00, 08 Feb 2025 Ajax technical director Al...